The Maverick Reserve Bank

How the St. Louis Fed Helped Shape the Nation's Monetary Policy

St. Louis Fed President Darryl Francis (left) chats with Frederic M. Peirce, chairman of the Bank's board of directors, in 1966.

The views of Maisel and Burns about the causes of inflation were widely held at the time, both within the Fed and among academic and business economists. However, they were not held by Darryl Francis, the president of the St. Louis Fed from 1966 to 1976. Citing the research of his staff economists, as well as of Milton Friedman, Karl Brunner and other academic economists, Francis blamed inflation on the Fed's monetary policies: "When we talk about the 'problem of inflation,' I think it is safe to say that the fundamental cause is excessive money growth." Further, Francis argued that "the cure [for inflation] is to slow down the rate of money expansion." 15

Burns and most other members of the FOMC largely discarded the idea that monetary policy was either a cause of or a cure for rampant inflation. At an FOMC meeting June 8, 1971, Burns argued: "Monetary policy could do very little to arrest an inflation that rested so heavily on wage-cost pressures. ... A much higher rate of unemployment produced by monetary policy would not moderate such pressures appreciably." Burns then said that he intended to continue to press the Nixon administration hard for an effective incomes policy (FOMC, Memorandum of Discussion, June 8, 1971, p. 51). Burns advocated government control of wages and prices, rather than monetary policy, to contain inflation. According to Burns, "The persistence of rapid advances of wages and prices in the United States and other countries, even during periods of recession, has led me to conclude that governmental power to restrain directly the advance of prices and money incomes constitutes a necessary addition to our arsenal of economic weapons." 16

As previously stated, the St. Louis Fed's Francis held a different view. At an FOMC meeting in December 1967, Francis noted some downsides of wage and price controls: "[They] raised problems of resource allocation; they interfered with freedom; and they were difficult to administer" (FOMC, Memorandum of Discussion, Dec. 12, 1967, pp. 54-55). At a subsequent meeting, he again argued against wage and price controls: "The adoption of administrative controls in attempting to hold down inflation, or to shorten the period of adjustment, would impose a great cost on the private enterprise economy. Serious inefficiencies would develop in the operations of the market system" (FOMC, Memorandum of Discussion, Dec. 15, 1970, p. 74). In Francis' view, "a freeze or other control programs could not be expected to effectively restrain inflation unless accompanied by sound monetary actions" (FOMC, Memorandum of Discussion, Oct. 19, 1971, p. 36).

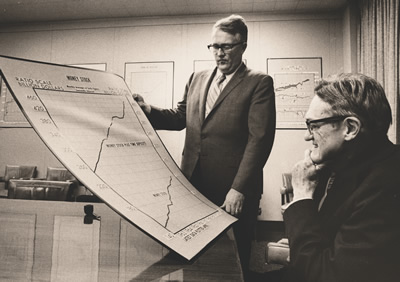

FIGURE: St. Louis Fed President Darryl Francis did not shy away from challenging Fed Chairman Arthur Burns and others on the FOMC at the time. Francis had faith in his researchers, whose data showed that the growth of the money supply led to a growth in inflation and, historically, to macroeconomic instability.

For Francis, "sound monetary actions" meant maintaining a moderate, stable growth of the money stock. This put Francis at odds with Burns and several other FOMC members. According to Jordan, the former St. Louis Fed research director who went on to become the president of the Cleveland Fed, "No one was paying attention to any kind of quantitative measures, and the ideas that [St. Louis Fed Research Director] Homer Jones and Darryl Francis supported at this Bank of looking at aggregates, looking at bank reserves, looking into money supply, was just out of tune with what everybody else was saying." 17

Burns explicitly argued against a focus on the money supply, saying at an FOMC meeting in 1971 that "the heavy emphasis that many people were placing on the behavior of M1 [a measure of the money stock] involved an excessively simplified view of monetary policy" (FOMC, Memorandum of Discussion, Feb. 9, 1971, p. 87). Further, Burns argued that the Fed could not reliably control the growth of the money stock even if it desired to do so: "All we can control over such brief periods [as short as three months] is the growth of member bank reserves; but a given growth of reserves may be accompanied by any of a wide range of growth rates of ... the money supply." 18

Francis again held a different view, which he made known in public forums as well as in FOMC meetings and correspondence with Burns and other FOMC members. For example, in a letter to Burns (Figure 2), Francis challenged claims made at a recent FOMC meeting that the growth of monetary aggregates was impossible to predict or to control: "Damn it all, Arthur, we here [at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis] could and did predict just such an outcome! Furthermore, there is a control mechanism which will assure much better results than we have achieved in the past by our reliance on short term interest rates [to conduct policy]." To bolster his case, Francis included with his letter an article by Albert Burger, a St. Louis Fed staff economist, and a memo by Robert Rasche, a visiting scholar at the St. Louis Fed and a future director of research at the Bank (appointed in 1999). 19

Francis' immediate predecessors as presidents of the St. Louis Fed—Delos Johns and Harry Shuford—had also argued for the use of monetary aggregates in the conduct and description of monetary policy. Of the three, however, Francis was the most vocal critic of System policy; he also served as president when inflation was rising and highly variable. During Francis' tenure, the St. Louis Fed became known as a maverick for its outspoken criticism of Fed policies and for its advocacy of an alternative approach. 20

The St. Louis Fed's very public criticism of the Fed's policies was often not welcomed by the Board and other Reserve banks. A few governors expressed the view that Reserve banks should stick to reporting on local economic conditions and not criticize System policy. One governor said, for example: "It is a weakness for a regional bank to concentrate on national matters. ... We have a fine staff in Washington." 21

At times, pressure on the Reserve banks to support System policy was intense. According to Lawrence Roos, who succeeded Francis as president of the St. Louis Fed in 1976, other Reserve banks would sometimes express support for St. Louis in private, but were unwilling to disagree with Burns and other members of the Board at FOMC meetings or in public. "I think some of them were concerned about their own Reserve bank budgets," Roos said. "They wanted to be on the right side of the chairman and the Board. ... [T]here was politics in the Open Market [Committee]." 22

Francis and his immediate predecessors were undoubtedly influenced by Homer Jones, the St. Louis Fed's director of research from 1958 to 1971. Jones had been a teacher and later a student of Milton Friedman, the University of Chicago economist who championed "monetarism" in both scholarly journal articles and popular writings and speeches. Friedman coined the phrase, "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." Further, he and other monetarists argued that fluctuations in money supply growth had historically been an important source of macroeconomic instability. Consequently, Friedman and other monetarists advocated monetary policies geared toward maintaining a modest, stable rate of growth of monetary aggregates.

Leonall Andersen, standing next to Homer Jones in 1971, co-authored a famous and influential paper titled "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilization." St. Louis Fed President Darryl Francis used this paper and subsequent research to promote a monetary policy based on controlling the growth of monetary aggregates.

Under Jones, the St. Louis Fed developed an international reputation for economic research and monetarist policy views. Former staff economists at the St. Louis Fed remember Jones as a hard-driving economist who insisted on precise arguments and strong empirical support for any claim. According to Jordan: "Homer drove everyone absolutely crazy. I think part of his method was to really make us angry. He was a total agnostic as far as both theory and empirical evidence. He would needle everyone to, 'Prove it to me. Where's your theory? Say it better. Where's your evidence?' "

Francis was similar, according to Jordan: "Darryl was the Harry Truman of the Federal Reserve System. He lived what was meant by the 'Show Me' state philosophy. He really believed, 'Well, OK, let's shine some light on it, and let's see,' and he would stand his ground. He didn't need a sign on his desk that says, 'The buck stops here.' Everybody knew that with Darryl, and he wasn't willing to be intimidated though the pressures were at times very considerable—especially after Arthur Burns became chairman of the Board of Governors—to stop what we were doing at this Bank."

Like Francis, Jones felt strongly that monetary policy had gone awry. According to R. Alton Gilbert, another St. Louis Fed staff economist at the time, Jones' "view was that the only way we could change it [i.e., policy] ... [was by] influencing public opinion outside the System and bringing pressure upon the Federal Reserve, and Homer Jones decided that we would do this through publications." 23 Accordingly, Jones marshaled his staff to conduct research for publication in the Bank's Review and other professional journals. Jones also introduced a series of publications that reported and analyzed monetary growth rate trends and other macroeconomic data. As noted by Gilbert, the roots of the Bank's online data and information services, such as Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), "go back to the leadership of Homer Jones." (See the essay "The History of FRED.")

Economic research played an important role in supporting Francis and other St. Louis Fed presidents in their monetary policy positions. The most famous and influential paper was written by Jordan and fellow St. Louis Fed researcher Leonall Andersen, titled "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilization." In that 1968 St. Louis Fed Review article, the authors reported empirical evidence that the growth of the money stock had a larger, more predictable and faster impact on the growth of nominal gross national product (GNP) than did fiscal policy actions. Francis used the Andersen and Jordan results and subsequent research to promote a monetary policy based on controlling the growth of monetary aggregates. At FOMC meetings, he frequently referred to his staff's forecasts of output and inflation under alternative money stock growth assumptions. 24

Homer Jones retired in 1971, and Darryl Francis retired in 1976. Although they were not able to persuade the FOMC to change course during their tenures, the Fed's organizational form ensured that their views were heard, both publicly and in policy deliberations. Pressure was brought to bear on the Fed to reduce inflation, and eventually the Fed did accept responsibility for inflation. Under Chairman Paul Volcker, the Fed finally adopted policies to control money stock growth and to lower inflation. The Fed never embraced monetary targeting wholeheartedly, but did come to recognize the importance of maintaining a credible commitment to price stability.

Photo of Darryl Francis presenting to a meeting of Mississippi bankers in 1947.

The Great Inflation era of the 1970s illustrates how the Fed's structure and FOMC composition promote open and frank discussion of policy views and ultimately can lead to better policymaking. Further, this episode in Fed history illustrates how the System's organization encourages innovation within the Reserve banks. The St. Louis Fed innovated by bringing cutting-edge monetary policy and macroeconomic research to policymaking. Eventually, that innovation was copied by other Reserve banks and by the Board. According to Jordan: "Our focus in St. Louis was ... on trying to be useful to the president in the decisions he had to make. ... That was rare in the Reserve banks and probably nonexistent at the Board of Governors. ... I'm sure that we were sending our president off much better prepared to engage in the important decisions that had to be voted on than just about anybody else."

The other Reserve banks then sought to emulate the St. Louis approach. Jordan said, "I think because of the competition among peers, over the subsequent years, the other Reserve bank presidents ... wanted to build up a staff that was able to help prepare them to also sit at the table and engage in a serious way as a policymaker."

The legacy of the maverick Reserve bank thus demonstrates that the Fed's decentralized structure, though established 100 years ago, remains vital and continues to benefit the Federal Reserve System and the nation.

ENDNOTES

15. See Francis, pp. 6-7.

16. "Some Problems of Central Banking." Address before the 1973 International Monetary Conference, June 6, 1973 (reprinted in Burns, p. 156).

17. Interview with Jerry Jordan, St. Louis Fed, April 11, 2012.

18. "Monetary Targets and Credit Allocation." Testimony before the Subcommittee on Domestic Monetary Policy, U.S. House Banking, Currency, and Housing Committee, Feb. 6, 1975.

19. Letter from Darryl R. Francis to Arthur F. Burns, January 14, 1972. Box D7, Folder St. Louis Fed (2). Gerald R. Ford Library.

20. See, for example, "Maverick in the Fed System," Business Week, Nov. 18, 1967, pp. 128-34.

21. Ibid.

22. Oral history interview of Lawrence Roos conducted by Richmond Fed economist Robert L. Hetzel, June 30, 1994.

23. Interview with R. Alton Gilbert. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Sept. 9, 2011.

24. See Hafer and Wheelock (1991) for more on the monetarist-oriented research and policy advocacy at the St. Louis Fed from the 1960s through the early 1980s.