Why Are Banks Shuttering Branches?

Thinkstock/ultramarine5

This post is part of a series titled “Supervising Our Nation’s Financial Institutions.” The series, written by Julie Stackhouse, executive vice president and officer-in-charge of supervision at the St. Louis Federal Reserve, appears at least once each month.

On Feb. 6, the Wall Street Journal published a startling statistic: Between June 2016 and June 2017, more than 1,700 U.S. bank branches were closed, the largest 12-month decline on record.1

Structural Shift

That large drop, while surprising, is part of a trend in net branch closures that began in 2009. It follows a profound structural shift in the number and size of independent U.S. banking headquarters, or charters, over the past three decades.

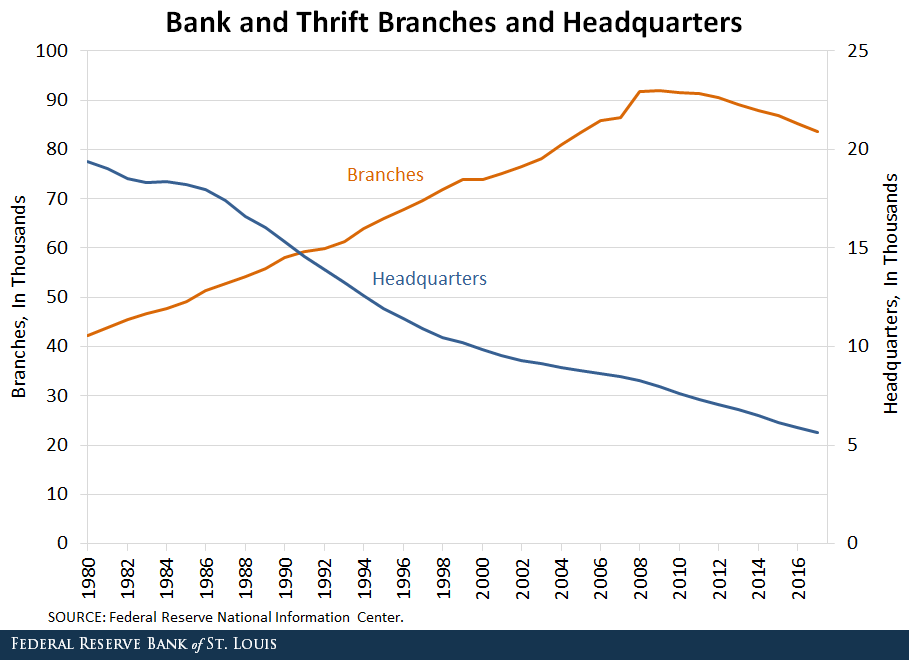

In 1980, nearly 20,000 commercial banks and thrifts with more than 42,000 branches were operating in the nation. Since then, the number of bank and thrift headquarters has steadily declined.

The reasons for the decline in charters and branches are varied. Regarding charters, the passage of the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act in 1994 played a significant role in their decline. Banks operating in more than one state took advantage of the opportunity to consolidate individual state charters into one entity and convert the remaining banks into branches. Almost all states opted in to a provision in the law permitting interstate branching, which led to a steady increase in branches.

Trend Reversal

Even before the number of charters declined, however, the number of branches grew steadily throughout the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s. It peaked in 2009, when the trend reversed, as seen in the figure below.

The initial wave of closings can be attributed to a wave of mergers and failed bank acquisitions following the financial crisis. There was an immediate opportunity to reduce cost through the shuttering of inefficient office locations. Branch closings were also influenced by earnings pressure from low interest rates and rising regulatory costs.

More recently, changing consumer preferences and improvements in financial technology have further spurred the reduction in branches. Customers increasingly use ATMs, online banking and mobile apps to conduct routine banking business, meaning banks can close less profitable branches without sacrificing market share.

Uneven Changes

The reduction in offices has not been uniform. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., less than one-fifth of banks reported a net decline in offices between 2012 and 2017, and slightly more than one-fifth reported an increase in offices.2

Just 15 percent of community banks reported branch office closures between 2012 and 2017. And though closures outnumber them, new branches continue to be opened. It’s also important to note that deposits continue to grow—especially at community banks—even as the number of institutions and branches decline.

The Industry of the Future

It seems inevitable that this long-term trend in branch closings will continue as consumer preferences evolve and financial technology becomes further ingrained in credit and payment services.

Although it is unlikely that the U.S. will end up resembling other countries with relatively few bank charters, it seems certain that consumers and businesses will increasingly access services with technology, no matter the size or location of bank offices. This change creates opportunities as well as operational risks that will need to be managed by banks and regulators alike.

Notes and References

[1] Ensign, Rachel Louise; Rexrode, Christina; and Jones, Coulter. “Banks Shutter 1,700 Branches in Fastest Decline on Record.” Wall Street Journal, Feb. 6, 2018.

2 Hinton, Nathan L.; Thieme, Derek K.; and Woodhead, Angela N. “Factors Shaping Recent Trends in Banking Office Structure for Community and Noncommunity Banks (PDF).” FDIC Quarterly, 2017, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 31-40.

Follow the Series

- Why Are Banks Regulated?

- Did the Dodd-Frank Act Make the Financial System Safer?

- Bank Supervision and the Central Bank: An Integrated Mission

- Why Are There So Many Bank Regulators?

- Why Didn’t Bank Regulators Prevent the Financial Crisis?

- Who Funds the Cost of Bank Supervision?

- Why Does the Fed Supervise Small Banks?

- Regulation and Regulatory Burden

- Why America's Dual Banking System Matters

- Fintech Interest in Industrial Loan Company Charters: Spurring the Growth of a New Shadow Banking System?

- Consumer Protection Laws and Regulations: Cost and Benefit Trade-offs

- Are Bank Holding Company Structures Still Beneficial?

- The Community Reinvestment Act’s History and Future

Citation

Julie L Stackhouse, ldquoWhy Are Banks Shuttering Branches?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Feb. 25, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions