Bank Supervision and the Central Bank: An Integrated Mission

This post is part of a series titled “Supervising Our Nation’s Financial Institutions.” The series, written by Julie Stackhouse, executive vice president and officer-in-charge of supervision at the St. Louis Federal Reserve, is expected to appear at least once each month throughout 2017.

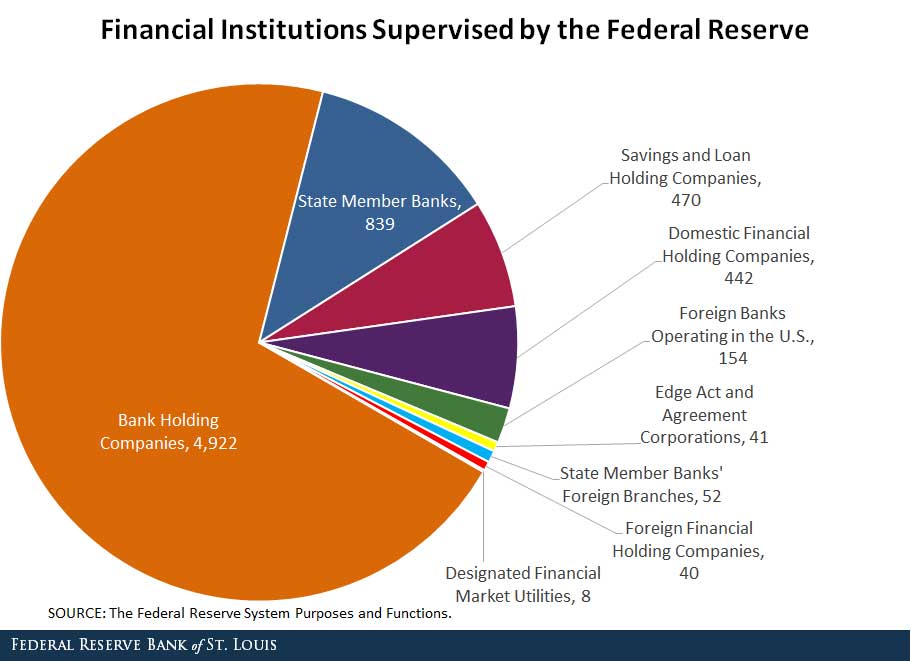

The Federal Reserve’s bank supervision and regulation duties are many and varied, and they reflect the depth and breadth of the nation’s financial institutions landscape. As illustrated in the figure below, the Fed supervises:

- Some of the nation’s smallest institutions as well as its largest

- The U.S. operations of foreign banks as well as the foreign operations of some domestic banks

- Holding companies of banks and savings and loans of all sizes

- Some of the infrastructure—called financial market utilities—that enables the smooth functioning of payments and other financial transactions systems

The Fed’s supervision responsibilities are integrally linked with other central bank functions. This is especially true for the nation’s very largest banks, whose size and interconnectedness make them major players in the national and world economies.

Conversely, the Fed’s ability to carry out its central bank functions—formulating monetary policy, fostering financial stability and lending from the discount window—depends in part on the information gathered in its supervisory responsibilities for institutions of all sizes.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policymakers depend on information provided by bank supervisors about banking market conditions, especially in times of financial stress, when determining the appropriate path of policy. In the early 1990s, for example, the Fed eased monetary policy more aggressively than it otherwise would have based in part on supervisory reports that rising loan delinquencies were straining bank balance sheets, portending tighter credit that would adversely affect consumer and business spending.1

More recently, supervisors assisted the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in modeling the effects of rising credit losses to the financial system and the economy during the financial crisis. Further, Fed relationships with foreign supervisory bodies provided key insight into financial market conditions in other nations that would have material effects on domestic firms and the U.S. economy.2

Financial Market Stability

The Fed’s supervisory expertise and authority have proven critical in the management of financial crises, from the 1970 bankruptcy of the Penn Central Railroad to the October 1987 stock market crash to the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession that followed. On-site examiners at major banks provided real-time analysis of funding needs and potential credit losses that allowed Fed officials to make more knowledgeable decisions about liquidity needs.

Even when the underlying crisis was not financial in nature, such as the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, supervisory relationships with affected financial institutions led to quick action to ensure liquidity and helped contain the financial and economic fallout from the attacks.3

Lender of Last Resort

One of a central bank’s core responsibilities is providing liquidity to financial markets. The Fed accomplishes this through a variety of discount window loan programs. Collateralized, short-term loans are extended to financial institutions by individual Reserve banks. To be able to extend credit to solvent firms that are illiquid, the Fed relies on intelligence it continuously gathers from the vast array of firms it supervises.

In short, the Fed is a more effective bank supervisor because of its central bank duties and a more effective central bank because it is a bank supervisor. This symbiotic relationship between central banking and bank supervision has shown its worth in ordinary times as well as times of financial distress.

In a future post, we’ll discuss how the Fed’s supervision and regulation responsibilities fit in with those of other financial regulators.

Follow the Series

- Why Are Banks Regulated?

- Did the Dodd-Frank Act Make the Financial System Safer?

- Bank Supervision and the Central Bank: An Integrated Mission

Notes and References

1 Bernanke, Ben. “The Public Policy Case for a Role for the Federal Reserve in Bank Supervision and Regulation,” Jan. 13, 2010.

2 See Bernanke.

3 See Bernanke.

Additional Resources

- Minneapolis Fed: The Economy and Why the Federal Reserve Needs to Supervise Banks

- On the Economy: Keeping a Watchful Eye

- On the Economy: Reflections of a Former St. Louis Fed Director

Citation

Julie L Stackhouse, ldquoBank Supervision and the Central Bank: An Integrated Mission,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, March 15, 2017.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions