Older Workers Account for All Net Job Growth Since 2000

“Prime-age workers” are those between 25 and 54.1 Numbering almost 100 million in December 2017, this age group is both the largest and most productive set of workers.2

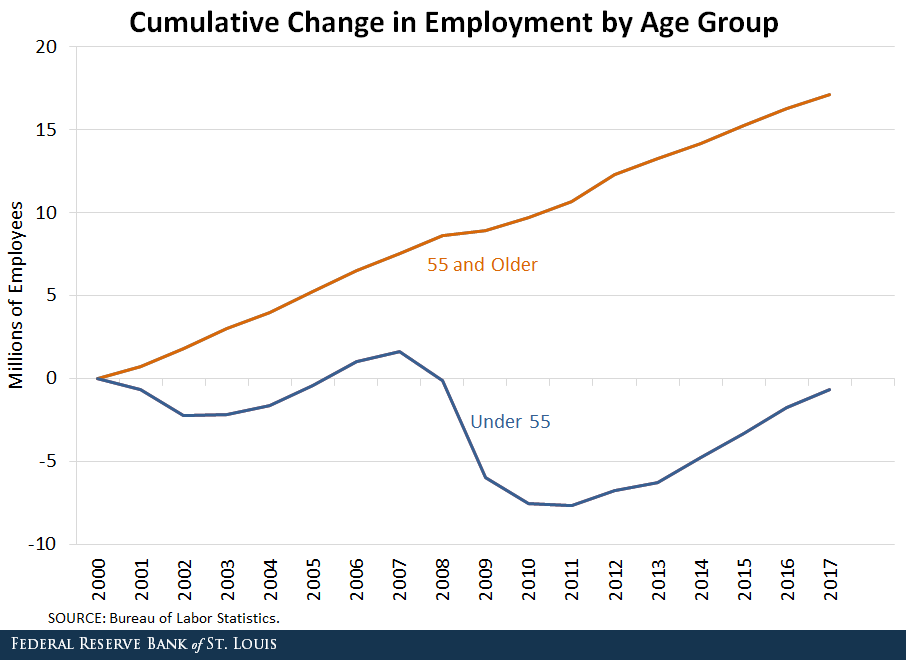

Yet, all of the net increase in employment since 2000—about 17 million jobs—has been among workers aged 55 and older, as seen in the figure below. Some economists fear that our aging workforce may be holding back economic growth.3

One important consideration on this topic is that the rapid aging of our workforce is unlikely to continue at this pace. Two important trends contributed to the rapid increase in the share of employment of older workers shown in the chart:

- A rapid increase in the share of older people in the population

- Diverging employment-to-population ratios by age group

The share of the U.S. adult population aged 55 or older increased from 27 to 36 percent between 2000 and 2017. This rapid change, due to the aging of the baby boomers, is unprecedented and is not expected to continue.

At the same time, the employment-to-population ratio of people aged 55 or older increased from 31 to 39 percent, while the ratio declined from 77 to 72 percent among people under 55. It seems unlikely, although not impossible, that these trends will continue to diverge so significantly.

Future Share of Older Workers

It is possible to forecast future employment shares by age group using Census Bureau population projections of detailed age groups and assumptions about future employment-to-population ratios.

For simplicity, I assumed that the age-specific employment-to-population ratios in the fourth quarter of 2017 will remain constant in the future. The results for employment by age group are shown in the table below for two break points—age 55 and age 65.

| Employment by Age Group in Millions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over and Under Age 55 | |||||

| 2000 | 2007 | 2017 | 2027 | 2037 | |

| Under 55 | 119.2 | 120.0 | 118.5 | 128.8 | 136.2 |

| 55 or Older | 18.4 | 26.2 | 35.5 | 40.0 | 40.3 |

| As Percent of Total | 13.4% | 17.9% | 23.1% | 23.7% | 22.8% |

| NOTES: Employment projections are based on Census Bureau projections of population by age group and age-specific employment-to-population ratios as of Q4:2017. Numbers are as of December each year. | |||||

| SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics for 2000, 2007 and 2017 and author's calculations for 2027 and 2037. | |||||

| Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis | |||||

| Employment by Age Group in Millions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over and Under Age 65 | |||||

| 2000 | 2007 | 2017 | 2027 | 2037 | |

| Under 65 | 133.5 | 140.5 | 144.5 | 154.5 | 161.4 |

| 65 or Older | 4.1 | 5.8 | 9.5 | 14.2 | 15.4 |

| As Percent of Total | 3.0% | 4.0% | 6.2% | 8.4% | 8.7% |

| NOTES: Employment projections are based on Census Bureau projections of population by age group and age-specific employment-to-population ratios as of Q4:2017. Numbers are as of December each year. | |||||

| SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics for 2000, 2007 and 2017 and author's calculations for 2027 and 2037. | |||||

| Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis | |||||

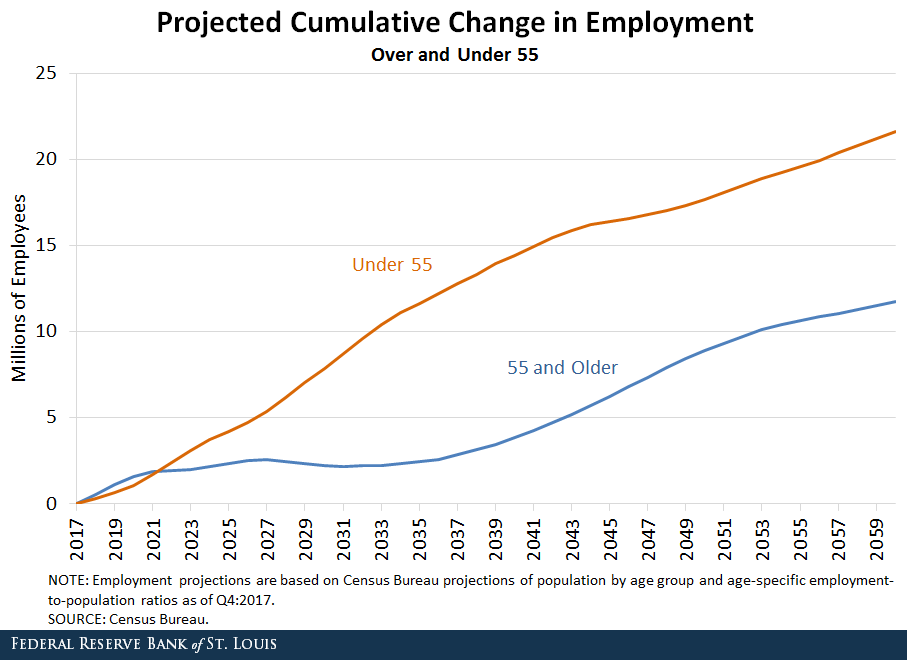

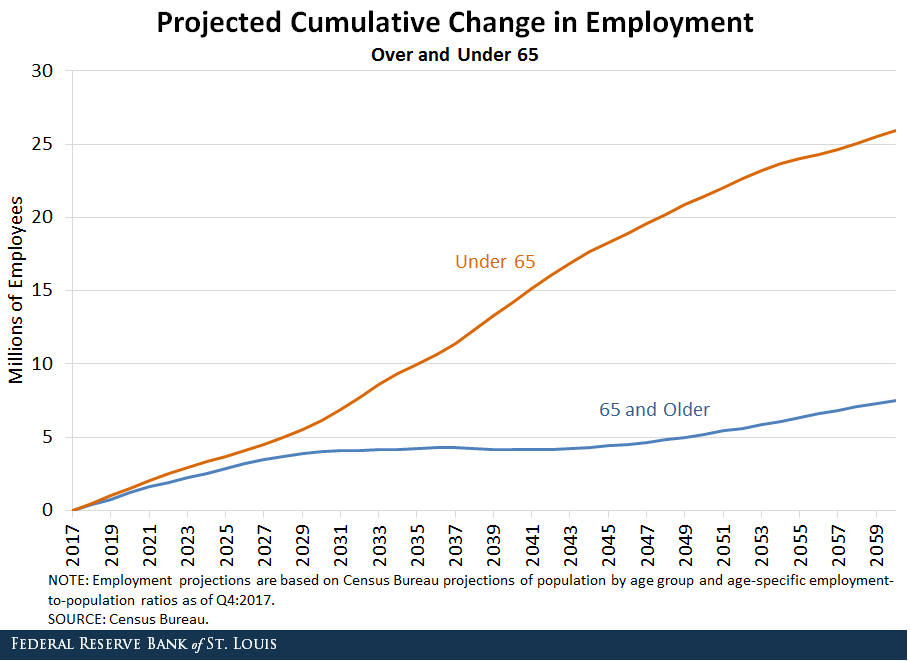

The first table shows that workers 55 and older are likely to become a slightly larger share of the workforce by 2027, but the share likely will decline after that. The second table shows that workers 65 and older are likely to become a larger share of the workforce over the next 20 years.

Long-Term Workforce Changes

The figures below show long-range projections of cumulative increases in employment for older and younger workers, using first age 55 and then age 65 as break points.

As the results in the tables suggested, the figures also show that the rapid increase in workers age 55 and older (or 65 and older) likely will not continue to outstrip younger workers for long. Within a decade or so, growth of younger workers (however defined) will once again begin to outstrip the growth of older workers.

A Silver Lining to the Graying of the Workforce

If it’s true that our aging workforce has held back economic growth in recent years, then the likely return to more normal patterns of job growth by age group is a reason to be optimistic. The Census Bureau expects the age structure of the population to shift permanently toward an older population, but the most rapid changes relevant for the workforce will have occurred within the next decade or so.

Notes and References

1 See Yellen, Janet L. “Inflation, Uncertainty and Monetary Policy,” Speech at the 59th Annual Meeting of the National Association for Business Economics, Cleveland, Ohio, Sept. 26, 2017.

2 See Krause, Eleanor; and Sawhill, Isabel. “What We Know and Don’t Know About Declining Labor Force Participation: A Review,” Brookings Institution, May 2017.

3 See Vandenbroucke, Guillaume. “Boomers Have Played a Role in Changes in Productivity.” The Regional Economist, Fourth Quarter 2017, Vol. 25, Issue 4.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Older Workers Accounted for All Net Employment Growth in Past 20 Years

- On the Economy: 3 Reasons Families Gain Wealth as They Age

- On the Economy: Five Simple Questions That Reveal Your Financial Health

Citation

William R. Emmons, ldquoOlder Workers Account for All Net Job Growth Since 2000,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 15, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions