The Evolution of the Job Finding Rate during the COVID-19 Recession

In two previous blog posts, we discussed the job separation and job switching rates amid the Great Recession and the COVID-19 recession. In this post, we will discuss another labor market condition indicator—the job-finding rate, or the rate at which unemployed workers transition into employment. While the unemployment rate tells us how much slack is in the labor market, the job-finding rate allows us to better understand the persistence of unemployment at the individual level.

Aggregate Job-Finding Rates

Data for our analysis come from the Current Population Survey (CPS), which tracks the monthly employment status of U.S. workers. To calculate the aggregate job finding rate for a given month, we simply take the proportion of previously unemployed workers who found employment.

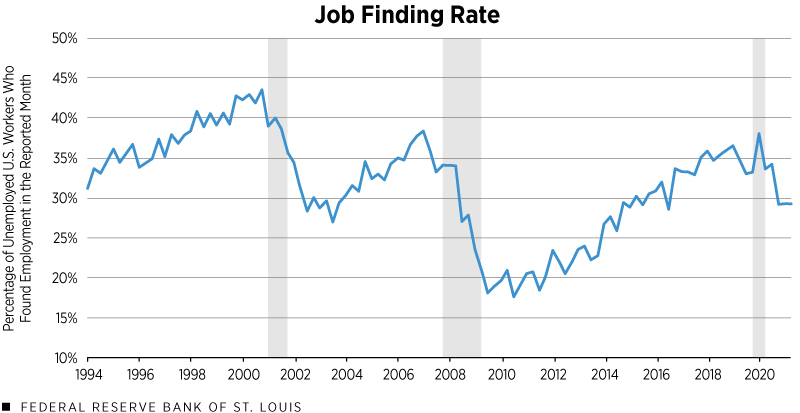

The figure below plots the time series of the seasonally adjusted quarterly average of the monthly job-finding rate between the first quarter of 1994 and the second quarter of 2021.

NOTES: Quarterly average of the monthly job finding rate. The data are seasonally adjusted and end in the second quarter of 2021. The gray shading represents recessions.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

The rate declined steadily over the course of the Great Recession (2007-09). In just over two years, it dropped from 38% in the first quarter of 2007 to 18% in the third quarter of 2009. The last quarter of 2009 saw the beginning of a gradual recovery. Over the following decade, the job finding rate fluctuated but slowly rose back to pre-recession levels by early 2020.

This upward trend reversed itself in 2020. As the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing recession unfolded, the job finding rate decreased from 38% to 29%. Since then, rates have stabilized but remain approximately 9 percentage points lower than they were before the pandemic.

Job Finding Rates for Occupation Switchers and Stayers

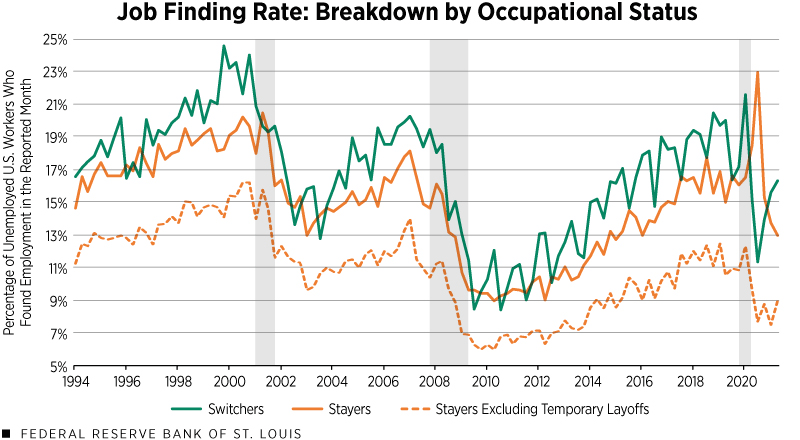

In addition to employment status, the CPS also tracks the occupations of employed and unemployed individuals. This allowed us to assess previously unemployed individuals who found work in each reported month and divide them into two groups: those who remained in the same line of work (stayers) and those who switched to a new one (switchers).We excluded unemployed individuals who were new to the labor force and individuals without occupational information. The figure below plots the job finding rates of occupation switchers and stayers following an unemployment spell, between the first quarter of 1994 and the second quarter of 2021. It also includes the job finding rate of occupation stayers who were not on temporary layoff.

NOTES: Stayers are those who returned to work in their previous occupation after being unemployed, while switchers were those who were reemployed in a new occupation. Quarterly average of monthly job finding rates for these two groups. The data are seasonally adjusted and end in the second quarter of 2021. The gray shading represents recessions.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

For most of the studied period, job finding rates of switchers and stayers have been very similar. They both, in turn, mirror the aggregate job finding rate. This holds true during the Great Recession, although the job finding rate of switchers suffered a larger decline. And during the studied period, the rate for occupation switchers was generally higher than that for stayers.

The similarity of job finding rates for switchers and stayers dissipated, however, during the COVID-19 recession and its aftermath. Since the first quarter of 2020, job finding rates of occupation switchers and stayers have moved strikingly in opposite directions. Following the aggregate trend, the job finding rate of switchers halved, from 22% in the first quarter of 2020 to 11% in the third quarter of that year. On the other hand, the job finding rate of stayers jumped from 16% to 23%. That is, workers were more likely to find reemployment by sticking to their previous occupation, which was atypical before the pandemic.

One potential explanation for the spike in the job finding rate of stayers is the fact that COVID-related job losses were more often temporary than permanent. Most workers who became temporarily unemployed during the recession eventually got called back to their former positions over the summer, as economic conditions slowly improved. Therefore, the spike may have reflected an influx of job seekers into reemployment at their previous workplace, which would be reported in the CPS as employment in the same occupation.

To test this hypothesis, we excluded workers on temporary layoff from our sample and recalculated the job finding rate of stayers. As shown by the dotted orange line in the second figure, the spike between the first quarter of 2020 and the third quarter of 2020 disappeared. Instead, this job finding rate of stayers less those on temporary layoff followed the decline in the aggregate rate, falling from 12% to 8%. Thus, the recalls of workers on temporary layoff drove the increase in the job finding rate of stayers in the first three quarters of 2020.

The Aggregate Job Finding Rate Revisited

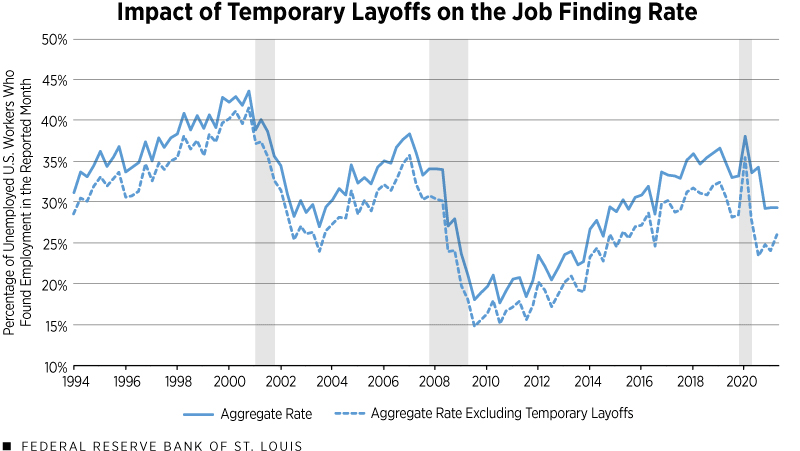

This finding implies that the aggregate rate was biased upward during the COVID-19 pandemic given the prevalence of recalls during 2020. Thus, when we calculated the aggregate job finding rate excluding workers on temporary layoffs, we found that the aggregate job finding rate indeed suffered an even greater decline, as shown in the figure below.

NOTES: Quarterly average of monthly job finding rates. The data are seasonally adjusted and end in the second quarter of 2021. The gray shading represents recessions.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

Conclusion

In recent decades, the job finding rates of occupation switchers and stayers following an unemployment spell have been comparable in magnitude and followed the aggregate trend. However, in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, they diverged drastically because recalls of workers on temporary layoff drove up the job finding rate of stayers and biased the aggregate rate upward. Once these workers were removed from the sample, we showed that, similarly to the job finding rate of switchers, the job finding rate of stayers declined and thus the aggregate job finding rate observed an even larger decline than previously measured.

These findings contextualize headline measures of the job finding rate, which underrepresent the severity of the pandemic’s impact on the ability of unemployed workers to find employment. Going forward, policy makers, who might be misled by the job finding rate, should consider the important role that temporary layoffs play in determining these measures.

Notes and References

- We excluded unemployed individuals who were new to the labor force and individuals without occupational information.

Citation

Serdar Birinci, Aaron Amburgey and Trần Khánh Ngân , ldquoThe Evolution of the Job Finding Rate during the COVID-19 Recession,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 28, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions