Credit Card Deleveraging during the COVID-19 Pandemic

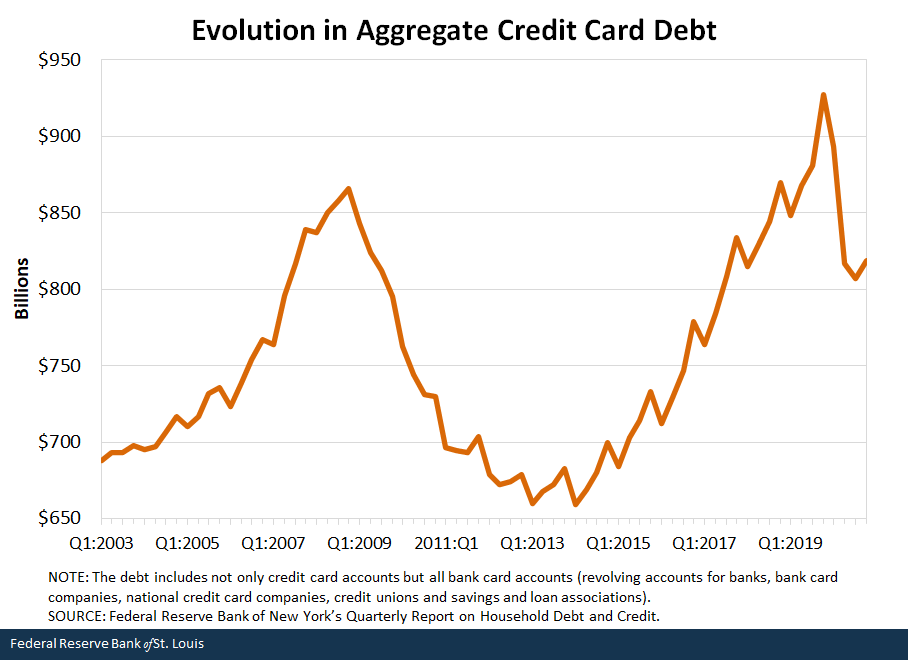

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, total credit card debtTechnically, the debt includes not only credit card accounts but all bank card accounts (revolving accounts for banks, bank card companies, national credit card companies, credit unions and savings and loan associations). in the United States dropped 13%, reaching a low of $807 billion by the end of third quarter of 2020. Prior to this decline, total credit card debt had reached a record high of nearly $930 billion. Using aggregate credit card debt data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the figure below shows the deleveraging pattern of the last two recessions, the Great Recession and the COVID-19 downturn.

This blog post uses individual level data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York/Equifax Consumer Credit Panel to show that although the evolution of credit card debt looks similar at the aggregate level during these two episodes, the underlying individual changes in credit card debt during these two events are quite different.

Debt Creation and Destruction

In a 2015 Economic Synopses essay, Juan Sánchez and Lijun Zhu explained that changes in total debt levels can be decomposed into creation of debt and destruction of debt.The methodology described in the Economic Synopses essay is based on a 2012 article by John Haltiwanger and a 2011 paper by Ana Maria Herrera, Marek Kolar and Raoul Minetti. Behind a change in aggregate debt, there are some individuals increasing debt but also some individuals decreasing debt. The sum of the changes of all individuals increasing debt constitutes “debt creation.” Similarly, the sum of the changes of all individuals reducing debt forms “debt destruction.”

The aggregate change reflects the difference between debt creation and debt destruction. Note that with this decomposition, a decline in aggregate debt can be attributed either to a reduction in creation (e.g., fewer people are increasing debt, or people are generally increasing it by less), an increase in destruction (e.g., more people are reducing debt, or people are generally reducing it by more), or both.

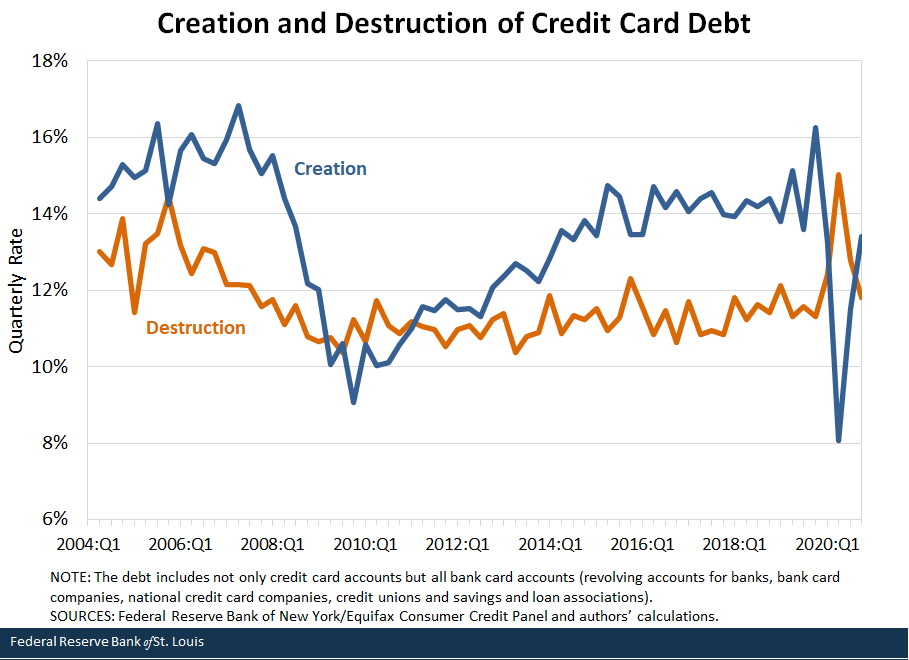

The figure below compares creation and destruction of credit card debt from the second quarter of 2004 to the fourth quarter of 2020; both series were seasonally adjusted.

Creation and Destruction of Credit Card Debt

Clearly, the behavior of creation and destruction during the COVID-19 recession is different than any time since 2004. The quarterly rate of debt creation reached the lowest level in the series at 8% in the second quarter of 2020. In the same quarter, the rate of debt destruction reached its peak at 15%. Thus, both creation and destruction contributed to the deleveraging observed in the second quarter of 2020.

The average creation rate in the quarters leading to the pandemic was 14%, so there was a decline of 6 percentage points in creation during the pandemic. Without any changes in debt destruction, this implies a deleveraging of 6%. Similarly, the average destruction rate in the quarters before the pandemic was 12%, so there was an increase in destruction of 3 percentage points. Thus, from an accounting point of view, we can conclude that two-thirds of the deleveraging was due to declining debt creation and the remaining one-third was due to increasing debt destruction. Notice that this behavior is different than the deleveraging in the aftermath of the Great Recession, when there was a slow decline in the creation of credit card debt but no significant increase in the destruction of credit card debt.

Why Did Debt Creation Slow and Debt Destruction Increase Dramatically in 2020?

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, strict social distancing, high unemployment and general uncertainty caused a slowdown in consumer spending, which in turn led to lower borrowing. A slowdown in borrowing leads to lower creation of debt, but it can also contribute to debt destruction if the new, lower amount borrowed is less than the amount payed at the end of the billing cycle.For example, let us say a cardholder has an initial balance of $100, spends $40 and pays $30 toward the balance in a month. Then in that month, the cardholder created $10 of debt. In the following month, this cardholder has an initial balance of $110 but decides to spend only $20 and still pay $30. The cardholder would then have reduced the card balance from $110 to $100, i.e., $10 of debt destruction. Another way to reduce balances from one period to the next is by increasing payments more than spending. According to this U.S. Census report, 15.7% of stimulus recipients used their first stimulus checkThe first round of stimulus began reaching recipients in April 2020. to pay down debts.

Conclusion

The large credit card deleveraging during 2020 was mostly due to the fact that people took on less debt than they would regularly do, but it was also because people repaid debt faster than in normal times. Both phenomena reversed quickly after the first months of the pandemic, making the credit card debt deleveraging of 2020 much shorter lived than during the Great Recession. The abrupt swings in economic uncertainty and the large U.S. government transfers were probably the main differences between the 2020 downturn and the Great Recession.

Notes and References

- Technically, the debt includes not only credit card accounts but all bank card accounts (revolving accounts for banks, bank card companies, national credit card companies, credit unions and savings and loan associations).

- The methodology described in the Economic Synopses essay is based on a 2012 article by John Haltiwanger and a 2011 paper by Ana Maria Herrera, Marek Kolar and Raoul Minetti.

- For example, let us say a cardholder has an initial balance of $100, spends $40 and pays $30 toward the balance in a month. Then in that month, the cardholder created $10 of debt. In the following month, this cardholder has an initial balance of $110 but decides to spend only $20 and still pay $30. The cardholder would then have reduced the card balance from $110 to $100, i.e., $10 of debt destruction.

- The first round of stimulus began reaching recipients in April 2020.

Additional Resources

Citation

Juan M. Sánchez and Olivia Wilkinson, ldquoCredit Card Deleveraging during the COVID-19 Pandemic,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 6, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions