Financial Distress and the Second Wave of COVID-19 Infections

Many observers have noted the recent shift in new COVID-19 cases from states that were previously hot spots (“first wave” states) to other states that have become new hot spots (“second wave” states).For the purpose of this article, we are defining the current surge as a second wave given its distinct geographical difference from the spring surge. In this post, we show that within first and second wave states, the evolution of cases has not been uniform.

In particular, county-level data suggest areas that entered the pandemic with higher levels of financial distress have systematically fared worse in the spread of infections than areas with lower levels of financial distress. This fact is noteworthy since our previous work shows that in response to COVID-related earnings losses, people in higher financial-distress areas are likely to draw down savings or increase debt, further exacerbating their already precarious financial state.

First Wave States

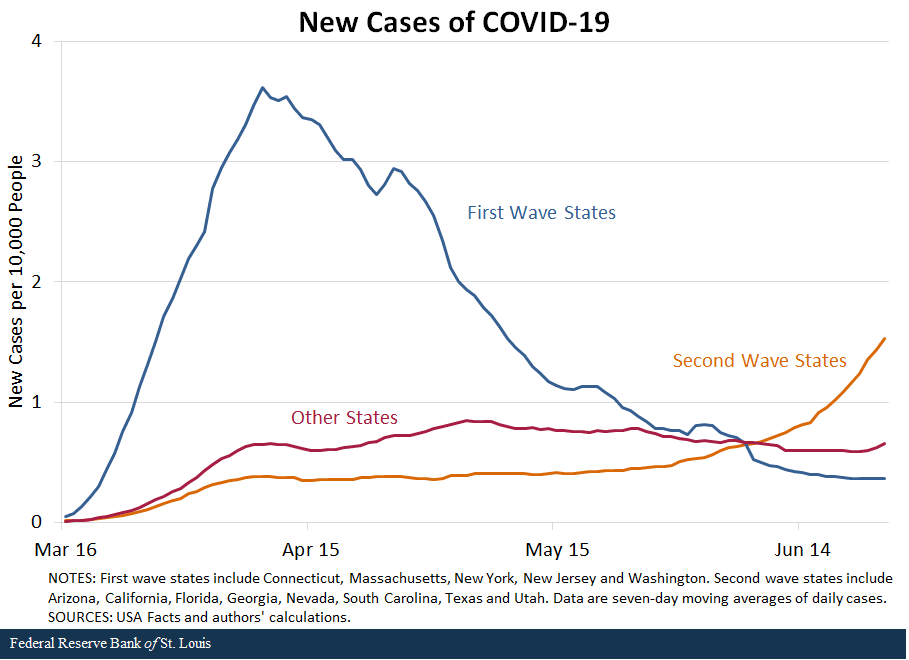

The figure below shows the different dynamics of the disease as it spread across states within the U.S.

Between April 15 and June 24, the seven-day moving average of new daily cases in first wave states (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Washington) fell from roughly 3.4 cases per 10,000 people (about 15,500 per day overall) to less than half a case per 10,000 people (about 1,700 per day overall).

In contrast, over the same time horizon, second wave states (Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Nevada, South Carolina, Texas and Utah) saw daily infections rise from less than half a case to slightly over 1.5 cases per 10,000 people (from 4,300 cases to 18,800 cases per day overall, respectively).

Reported daily cases in the remaining states have remained somewhat stable, averaging about 0.7 cases per 10,000 people (roughly 11,100 cases per day) over the same period.

Following our previous work, we next analyzed whether the spread of infection among first or second wave states has differed by financial distress. As before, distress is measured by difficulty in making timely payments on credit card debt.Specifically, we define level of financial distress as the percentage of population that has been delinquent on a credit card payment for 30 days or more at some point over the course of a year. We divided all U.S. counties into five groups, or "quintiles," defined by the incidence of financial distress. Counties with a financial-distress incidence in the bottom 20% of all counties are in group one (Q1), while counties in the top 20% are in group five (Q5), and so on.

Second Wave States

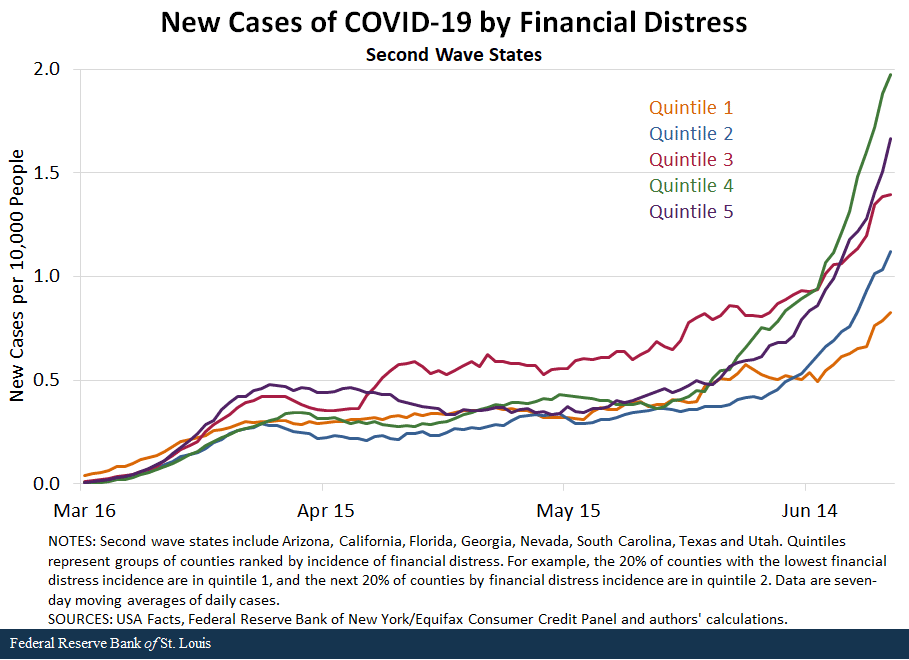

Focusing first on new hot spot, or second wave states, the next figure shows the very different time paths of new cases by the degree of distress.

This figure clearly shows that the growth in new cases within second wave states has been most rapid in high financial-distress counties relative to low financial-distress counties. For example, relative to May 15 levels, in Q4 and Q5 counties, new cases have grown from 0.4 cases per 10,000 people (1,000 cases per day overall) to nearly 2 cases per 10,000 people (more than 5,000 cases overall). In contrast, new cases in Q1 counties—those with the lowest levels of financial distress—have grown from roughly 0.3 cases per 10,000 people (380 cases per day) to 0.8 cases per 10,000 people (1,000 cases per day overall). Thus, while case growth in all second wave counties has risen, it appears to have risen by more in high financial-distress counties.

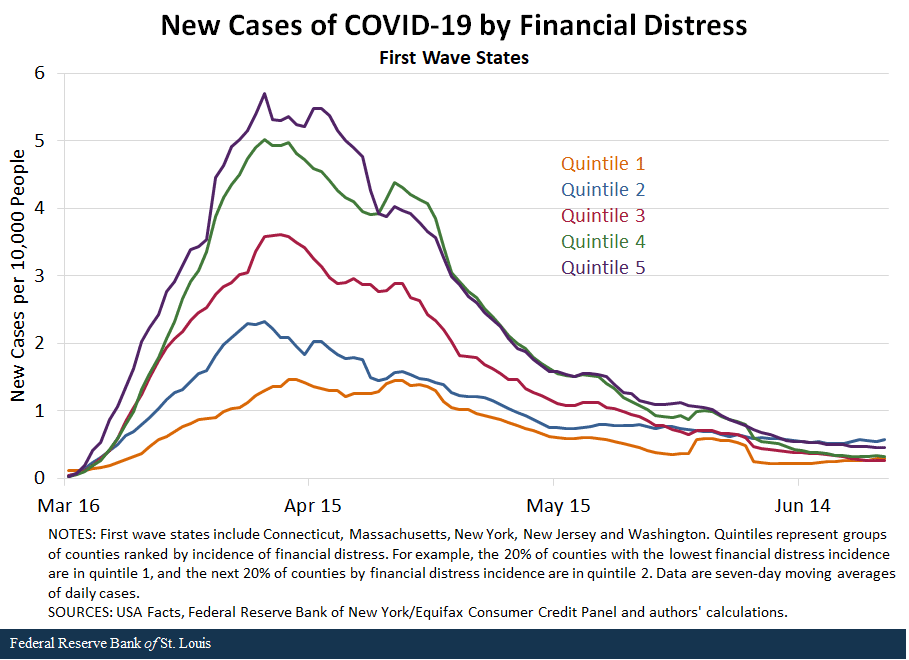

On a more positive note, the improvement in daily case growth within old hot spots, or first wave states, has been associated with substantial decreases in the number of cases among higher financial-distress counties (albeit from very elevated levels), as shown in the next figure.

This figure shows that while daily cases reached a peak of 5.7 cases per 10,000 people (3,700 cases per day overall) among Q5 counties in mid-April, the spread of COVID-19 has since subsided to roughly half a case per 10,000 people (300 cases per day overall) in late June.

Daily case growth in Q1 counties has also declined, but from a lower peak of 1.5 cases per 10,000 people (1,200 per day overall) to about 0.3 cases per 10,000 people (250 cases per day overall). Thus, while case growth in higher financial-distress counties remains above their lower financial-distress counterparts, the gap has narrowed considerably.

The Rest of the Country

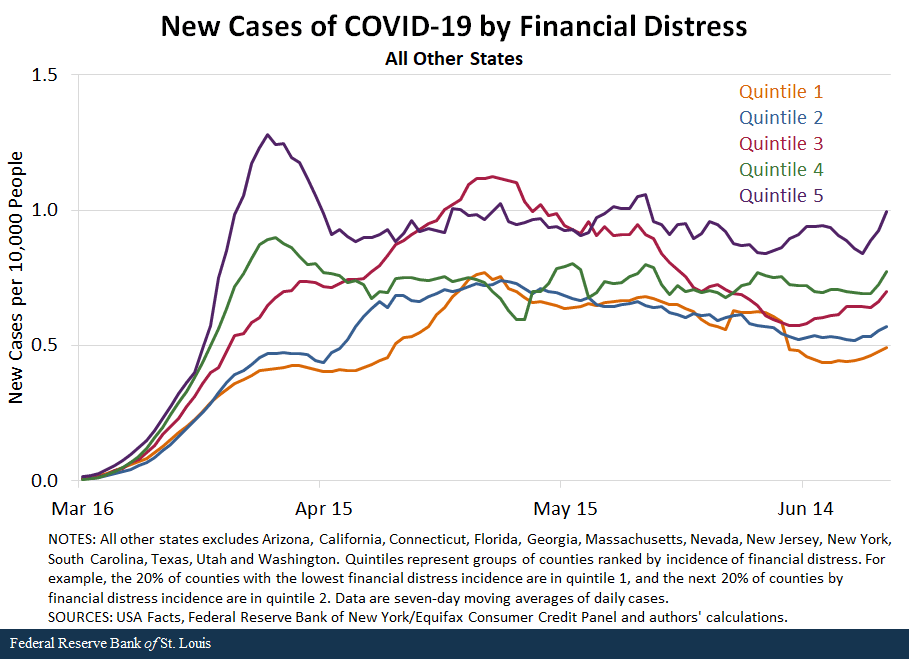

Lastly, the figure below shows that the steady case growth among all other states in the nation masks important differences by financial distress. As with the previous figures, it reveals that higher financial-distress counties have experienced rates of infection nearly twice as high as their lower financial-distress counterparts. Additionally, this figure reveals that these differences have remained fairly stable since the pandemic began.

What might be driving the differences in daily case growth by financial distress? Our previous work highlighted that, in general, areas of higher financial distress tend to have higher employment shares in leisure and hospitality. Reopenings have disproportionately affected these kinds of activities. Moreover, an earlier blog post by St. Louis Fed Economist Fernando Leibovici showed that workers in these kinds of sectors require relatively close physical proximity to others. Combining these two factors, it is perhaps not so surprising that areas with high financial distress are driving the bulk of infection increases.

Notes and References

1 For the purpose of this article, we are defining the current surge as a second wave given its distinct geographical difference from the spring surge.

2 Specifically, we define level of financial distress as the percentage of population that has been delinquent on a credit card payment for 30 days or more at some point over the course of a year.

Additional Resources

- St. Louis Fed’s COVID-19 resource page

- On the Economy: COVID-19 and Financial Distress: Vulnerability to Infection and Death

- On the Economy: Reading the Labor Market in Real Time

Citation

Juan M. Sánchez, ldquoFinancial Distress and the Second Wave of COVID-19 Infections,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, July 6, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions