Older Millennials Experience Pandemic Hardships Unequally

In a recent blog post, we found that older millennials (which we define as those born in the 1980s) had made some strides in wealth accumulation between 2016 and 2019, despite our previous description of them as a potentially “lost” generation. We also found that those relative gains in wealth—defined as net worth—were disproportionately made by white or college-educated millennials.

This post shows how various groups of older millennials fared during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of labor market outcomes, financial well-being and housing insecurity.

The same groups that were furthest below wealth expectations in 2019 (Black, Hispanic and less-educated households) were the ones more likely to be experiencing significant financial insecurity during the pandemic. This may inhibit these American families from recovering economically and lead to prolonged financial hardship and a lack of upward mobility. The result will be a continued K-shaped recovery for older millennials.

Lost Employment and Income

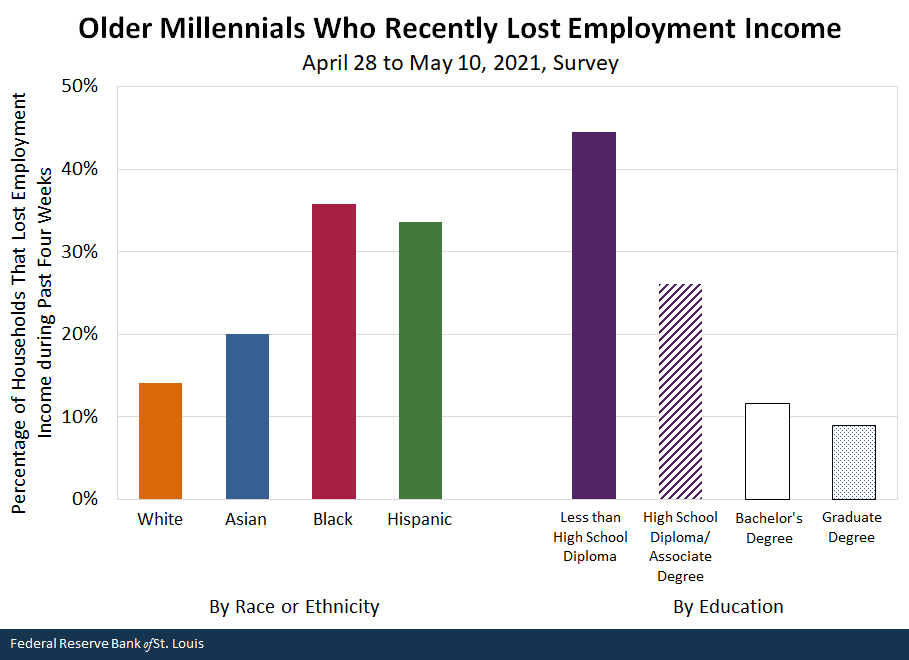

The pandemic continues to cause widespread disruptions in the labor market, resulting in lost employment income for many families, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020-21 Household Pulse Survey. Among older millennials, 36% of Black families and 34% of Hispanic families reported lost employment income in the past four weeks, according to a survey conducted between late April and early May 2021; the results can be seen in the figure below. In contrast, about 14% of white families and 20% of Asian families experienced similar disruptions.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020-21 Household Pulse Survey.

NOTES: Older millennials are those who were born in the 1980s. Hispanic Americans can be of any race.

Separately, a breakdown by education shows a clear pattern in which the likelihood of lost income falls as educational attainment increases. A four-year college degree continues to be strongly associated with better financial outcomes—in this case, a 12% likelihood of lost income versus 26% or higher for those without a four-year degree.

For those with a graduate degree, the likelihood of lost income was even lower (around 9%). The ability to telework partly explains this trend, with highly educated older millennials (i.e., those with at least a bachelor’s degree) being more than 2.6 times more likely to telework in November 2020 than less-educated millennials, according to the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED).

Additionally, older millennials in groups more likely to be experiencing financial hardships prior to the pandemic also had more highly elevated unemployment rates, according to data from the Current Population Survey. Older Black and Hispanic millennials and older millennials lacking a bachelor’s degree had unemployment rates of 8.9%, 5.9% and 7.1%, respectively, in April 2021–3.3, 1.3 and 1.7 percentage points higher than the rates in March 2020.

In contrast, older white millennials and older millennials with at least a bachelor’s degree had essentially recovered to pre-pandemic levels by April 2021, with unemployment rates of 3.9% and 2.8%, respectively.Nonseasonally adjusted unemployment rates for the civilian noninstitutionalized population born in the 1980s. Furthermore, even eight months into the pandemic (in November 2020), white and more-educated older millennials were less likely to say they were worse off financially than in the previous year, suggesting that many faced fewer financial hardships and recovered earlier. These households are likely contributing to the groundswell of personal savings observed during the pandemic.

Housing Insecurity

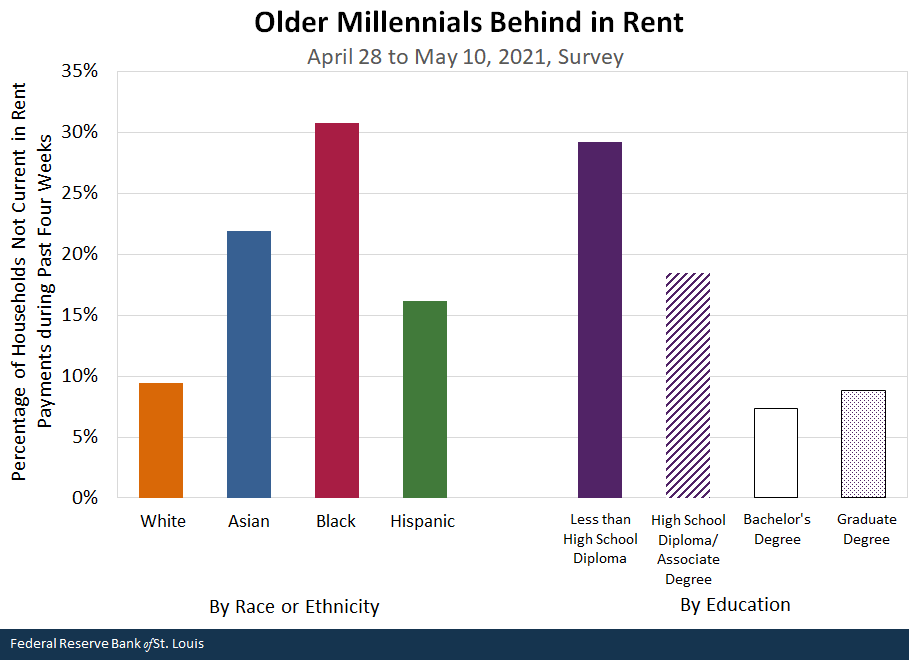

As families dealt with lost income, some fell behind on financial obligations such as rent or mortgage payments. The first figure below shows that close to 1 in 3 older Black millennial renters wasn’t current on rent as of late April to early May. Older Asian and Hispanic millennial families also experienced elevated rates of rent delinquency.

In contrast, roughly 1 in 10 older white millennial renters had fallen behind. Education was also strongly associated with renter hardship: Older millennials with at least a four-year degree had less than half the rate of rent delinquency as those without.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020-21 Household Pulse Survey.

NOTES: Older millennials are those who were born in the 1980s. Hispanic Americans can be of any race.

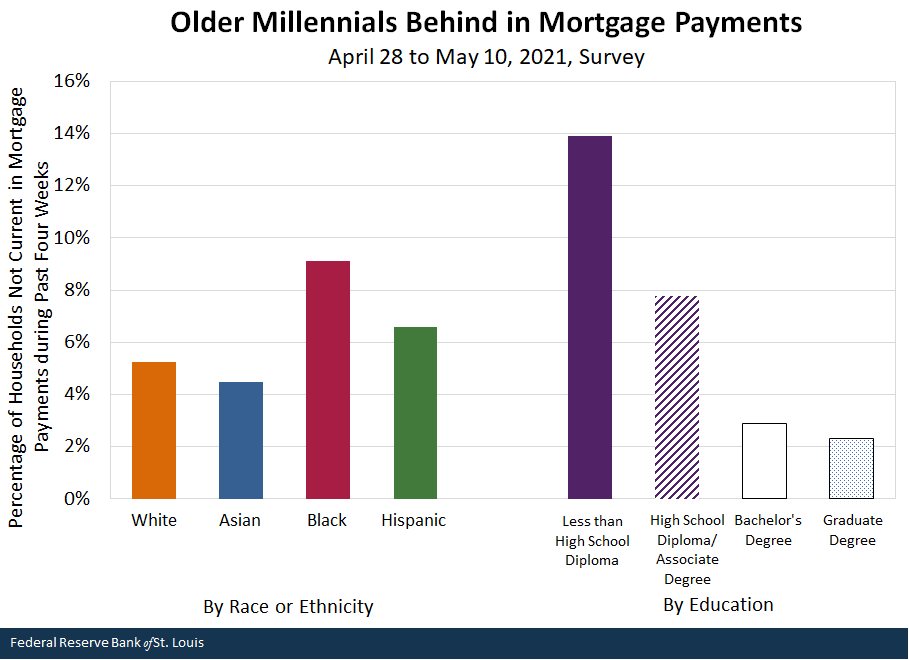

The figure below shows that delinquency rates were uniformly lower among mortgage holders than renters for all groups. Interestingly, differences in mortgage delinquency were less pronounced across racial and ethnic groups. In contrast, a similar hierarchy of delinquency was observed by education.

In other words, race and ethnicity had less of a relationship with mortgage delinquency than education, while both demographic factors were strongly related to renter hardship.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020-21 Household Pulse Survey.

NOTES: Older millennials are those who were born in the 1980s. Hispanic Americans can be of any race.

Importantly, there have been lengthy moratoriums on evictions and foreclosures during the pandemic, which have been an important resource for many families who have fallen behind. However, it is unclear if these families will be able to catch up with their missed payments when those supports are discontinued.

Towards Greater Financial Resilience

Older nonwhite millennials and older millennials who lack a four-year college degree have clearly borne disproportionate levels of financial distress during the pandemic. Because these data offer only a snapshot of overall insecurity, it’s difficult to speak to why these families have experienced so much hardship during the pandemic. However, a lack of emergency savings likely played a role.

Emergency savings can be thought of as a form of “private insurance” for when a family falls on tough economic times. While this buffer has been shown to be critically important, too few families have meaningful amounts of it: Less than half of older millennials had saved at least three months of emergency funds (and less than a third of older Black or less educated millennials had).

For many of these families, building up emergency savings is not simply a matter of saving more (especially, at the right times) but also having more capacity to save. Dealing with that capacity requires taking a wholistic view of family finances. This includes addressing rising costs (and debts) of living (e.g., college costs, rising rents and home prices), weak earnings growth and access to affordable and high-quality investments (e.g., portable retirement accounts with sidecar savings accounts).

Notes and References

- Nonseasonally adjusted unemployment rates for the civilian noninstitutionalized population born in the 1980s.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Household Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Regional Economist: Foreclosure Rate Drops during COVID-19 despite Dip in On-Time Mortgage Payments

- Institute for Economic Equity: The Demographics of Wealth

Citation

Lowell R. Ricketts and Ana Hernández Kent, ldquoOlder Millennials Experience Pandemic Hardships Unequally,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, July 6, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions