Did the Fed’s Dollar Swap Lines Work?

In a previous blog post, we explained two of the Federal Reserve’s recent actions in the international capital market: the expansion of its dollar swap lines and the creation of the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility.FIMA repos are similar to dollar swap lines: FIMA account holders borrow U.S. dollars for a set time and at a set rate. However, instead of exchanging foreign currency for dollars, they exchange U.S. Treasury securities they own. These actions made it easier for foreign central banks to obtain U.S. dollars and potentially alleviated dollar shortages caused by an increased demand for the dollar during the COVID-19 recession.

But were these policies truly effective? To find out, we analyzed cross-currency bases between U.S. dollars and select international currencies.

What Are Cross-Currency Bases?

A “cross-currency basis” can be thought of as the cost to invest in one currency using another. Consider an example: at time t, an investor trades one currency (the euro, €) for another (the U.S. dollar, $) at the current exchange rate (St), and saves the new currency for some time (m) at its market interest rate (r$t,t+m). Simultaneously (at time t), the investor agrees to trade however much of the new currency the person will have at a future time (t + m) back to the original currency at a “forward exchange rate” (Ft,t+m).

If investing in the new currency were “costless,” the investor, after trading the investments back to the original currency, should make as much money as if the investor had simply saved the original currency at its own market interest rate (r€t,t+m).Here, we mean an investment in a foreign currency is “costless” not in the sense that there are no transaction fees, but in the sense that (assuming there are no transaction fees), investing in said currency would be just as lucrative as investing in one’s domestic currency. The “cross currency basis” (bt,t+m) quantifies the degree to which the investment is not costless:

1 + r$t,t+m = St/Ft,t+m (1 + r€t,t+m + bt,t+m)

Where bt,t+m < 0 means investing in one currency ($) using another (€) is less lucrative than simply investing in the original currency (€).This would immediately imply that investing the other way around (using U.S. dollars to invest in euros) is more lucrative than investing in that currency (U.S. dollars) directly.

Historically, the basis between most currencies has been close to zero—a relationship known as “covered interest parity.”See, for example, Falk Bräuning and Kovid Puria’s 2017 paper. The intuition for why this should be close to zero is clear. Since both current and forward exchange rates and all interest rates are known at time t, if bt,t+m ≠ 0, investors with one currency can make more money investing in the other currency than in their own; the ensuing demand for that currency from investors would alter exchange rates until both investment options were equally lucrative. However, heightened concerns about investment and loaning risks, increased demand for dollars, and subsequently constrained access to dollars in times of turmoil push the basis between U.S. dollars and most foreign currencies substantially downward, making it a prime indicator of international dollar shortages and funding strains.Interestingly, many cross-currency bases have remained consistently nonzero since the Great Recession, suggesting causes besides the mostly transient ones focused on here; see, for example, Eugenio Cerutti, Maurice Obstfeld and Haonan Zhou’s 2019 paper for a more in-depth discussion.

The Response to the Fed’s Actions

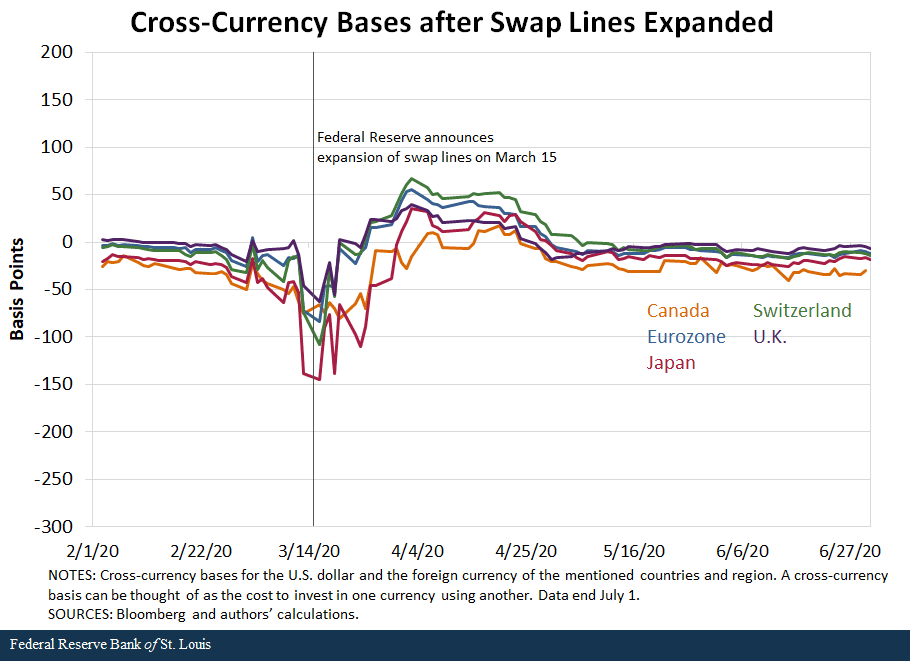

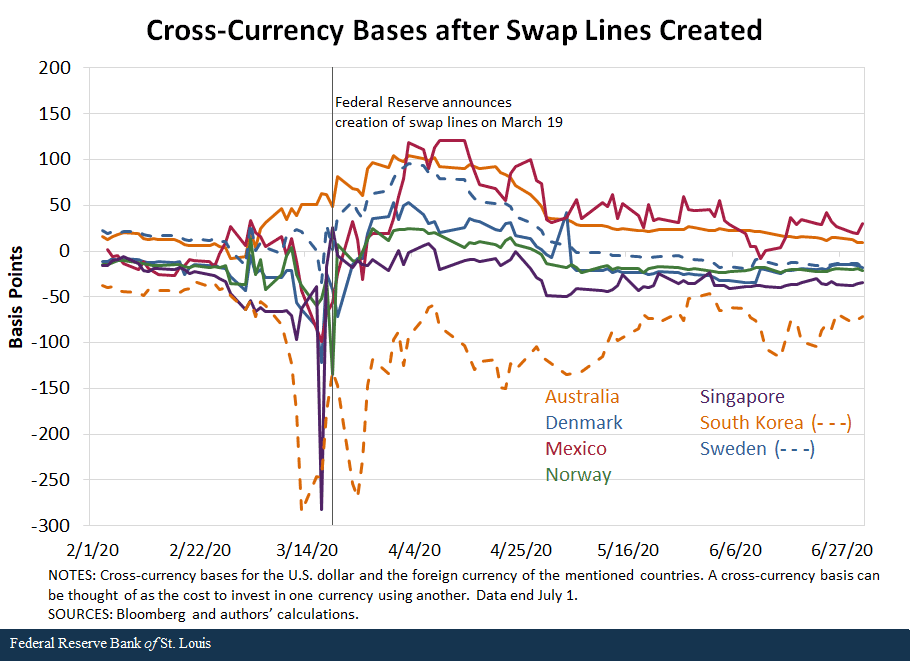

The figures below show the U.S. dollar–foreign currency bases that correspond to the foreign central banks whose dollar swap lines the Fed either expanded or created in March; the vertical line in each figure marks the day the Fed announced these expansions or creations.Note that temporary swap lines were also created with the latter group of banks during the Great Recession; see our earlier post for a description of these groups. Brazil and New Zealand (the two other countries with whom the Fed reinstituted swap lines) are excluded from our analysis because of the lack of data.

The cross-currency bases for almost all currencies fell substantially in the weeks before the Fed announcements. After the Fed’s actions, the bases spiked upwards before settling to their pre-recession states, where they largely remain today.The U.S.–Australia basis is the notable exception here, as Australian banks consistently supply U.S. dollars to the international market; see Annex F of “U.S. Dollar Funding: An International Perspective” for an overview of this dynamic. Together, these facts indicate that there were indeed widespread dollar shortages and that the swap lines successfully alleviated them.

Running a similar analysis of the cross-currency bases with other foreign currencies reveals a similar pattern, implying either that the FIMA repo facility had a similar effect or that the swap lines indirectly alleviated dollar shortages elsewhere. Either way, these results indicate that the Fed’s expanded swap lines and its creation of the FIMA repo facility accomplished their goals.

Notes and References

- FIMA repos are similar to dollar swap lines: FIMA account holders borrow U.S. dollars for a set time and at a set rate. However, instead of exchanging foreign currency for dollars, they exchange U.S. Treasury securities they own.

- Here, we mean an investment in a foreign currency is “costless” not in the sense that there are no transaction fees, but in the sense that (assuming there are no transaction fees), investing in said currency would be just as lucrative as investing in one’s domestic currency.

- This would immediately imply that investing the other way around (using U.S. dollars to invest in euros) is more lucrative than investing in that currency (U.S. dollars) directly.

- See, for example, Falk Bräuning and Kovid Puria’s 2017 paper. The intuition for why this should be close to zero is clear. Since both current and forward exchange rates and all interest rates are known at time t, if bt,t+m ≠ 0, investors with one currency can make more money investing in the other currency than in their own; the ensuing demand for that currency from investors would alter exchange rates until both investment options were equally lucrative.

- Interestingly, many cross-currency bases have remained consistently nonzero since the Great Recession, suggesting causes besides the mostly transient ones focused on here; see, for example, Eugenio Cerutti, Maurice Obstfeld and Haonan Zhou’s 2019 paper for a more in-depth discussion.

- Note that temporary swap lines were also created with the latter group of banks during the Great Recession; see our earlier post for a description of these groups. Brazil and New Zealand (the two other countries with whom the Fed reinstituted swap lines) are excluded from our analysis because of the lack of data.

- The U.S.–Australia basis is the notable exception here, as Australian banks consistently supply U.S. dollars to the international market; see Annex F of “U.S. Dollar Funding: An International Perspective” for an overview of this dynamic.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: What Are the Fed’s Dollar Swap Lines and FIMA Repos, and Why Do They Matter?

- On the Economy: Key Elements of the Fed’s New Monetary Policy Strategy

- On the Economy: V-Shaped Recovery Eludes G-7 Countries

Citation

Sungki Hong and Devin Werner, ldquoDid the Fed’s Dollar Swap Lines Work?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 24, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions