Did China's One-Child Policy Really Have an Effect?

In 1980, China put its well-known one-child policy into law. Family planning already existed, but the implementation of the one-child policy was, on the surface, the most drastic step toward curbing population growth in China.

After 30 years, the policy has been phased out. In 2013, the Chinese government authorized parents to have two children if one of them is an only child. By 2016, two children were allowed for all parents.

How effective were the Chinese in controlling their demography? Was the one-child policy effective? Will the removal of the policy lead to an increase in births?

The last question is, of course, the most critical today. This is because the main motivation for removing the one-child policy seems to be that Chinese authorities fear the aging of their population.

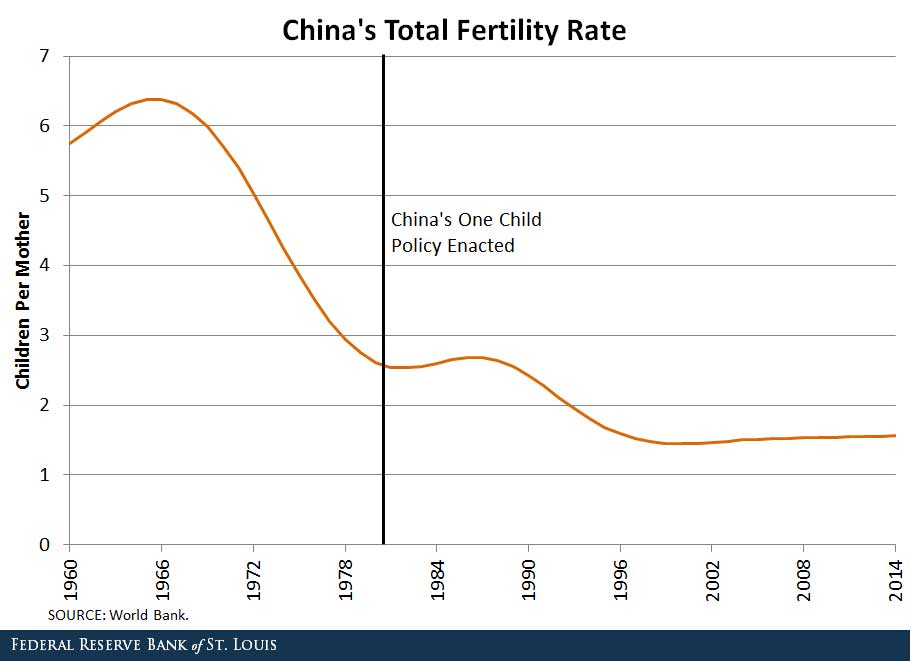

The figure above shows China’s total fertility rate, a measure of the number of births a woman who enters her reproductive life in a given year would have. Women entering their reproductive lives in the 1960s gave birth to an average of about six children. Today, this number is between one and two.

Births Already on the Decline

What is remarkable about this figure is that it shows a dramatic decline in fertility before the one-child policy was put in place. Fertility fell from more than six in the mid-1960s to less than three in 1980.

This raises questions as to the need for, and possibly the effectiveness of, the policy. Suppose that, whatever the causes of this decline were, they were still acting after the policy was put into place. This would imply that the one-child policy itself may not have been as effective as it may appear.

Why the Pre-Policy Decline?

There are two leading candidates for explaining the pre-1980 drop in fertility. First, family planning existed before the one-child policy became a part of it. Pressure was placed on Chinese men and women about the “appropriate” age at which to marry, about the number of children to have and about how rapidly. A 1994 paper by researchers Judith Banister and Christina Wu Harbaugh argued that these measures alone were effective enough to explain the pre-1980 decline, before the one-child limit.1

Second, China was growing during the 1970s. It is therefore possible that it experienced the same declining trend in fertility caused by growth that all currently developed countries experienced at some point. This is typically referred to as the “demographic” transition.

What will happen to Chinese fertility as family planning (the one-child policy in particular) is removed from law? This, of course, no one knows. But some ideas can be entertained.

Return to the notion of the demographic transition, i.e., that fertility tends to decline as countries get richer. It is well-known that China grew fast over the past 20 years. Thus, it is possible that today’s fertility rate should be low, and people may not want to have two children even if allowed.

If this is the case, then Chinese births may not increase in the near future or may do so only very slightly. China’s aging problem will take decades to solve.

Notes and References

1 Banister, Judith; and Harbaugh, Christina Wu. “China’s Family Planning Program: Inputs and Outcomes,” Census Bureau’s Center for International Research, CIR Staff Paper No. 73, June 1994.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Russia’s Demographic Problems Aren’t New

- On the Economy: Lifetime Education Benefits Have Never Been So High

- On the Economy: How World War I Changed Marriage Patterns in Europe

Citation

Guillaume Vandenbroucke, ldquoDid China's One-Child Policy Really Have an Effect?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Oct. 27, 2016.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions