Do Rises in Oil Prices Mean Rises in Food Prices?

Prices for agricultural commodities have been rising over the past 10 years. During the same period, crude oil prices have also increased substantially. The simultaneous rise in the price for agricultural inputs and crude oil has raised new questions about whether an increase in oil prices translates to increased food prices, an occurrence called pass-through.

How Can Oil Affect Food Prices?

The most common explanation for oil price pass-through is related to energy policy. In 2005, U.S. energy policy changed to increase the use of biofuels in gasoline production, increasing demand for ethanol.

Because gasoline is made primarily of oil and ethanol, corn competes with oil as an input. This means that increasing crude oil prices (the other main input into gasoline) could translate to higher corn prices. Corn is used not only to make food but also as animal feed, so the costs could transfer through grains, meat and dairy.

The Other Way Around?

However, there is also a case for causality in the other direction. Economists Christiane Baumeister and Lutz Kilian identified a case for increased food prices causing higher oil prices in a 2012 study.1 They pointed out that increasing agricultural activity in the developing world combined with increased farm income lead to higher demand for farm machinery and for oil to run the machinery. This increase in demand could raise prices of both agricultural commodities and crude oil.

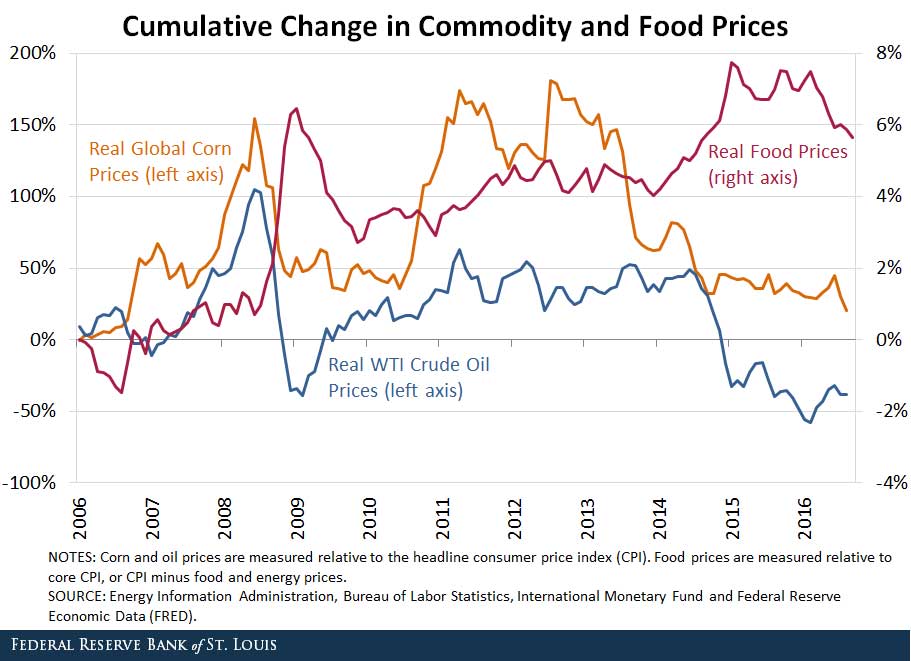

The figure below plots the cumulative change since 2006 in consumer food prices, global corn prices and global WTI crude prices. Oil and corn prices are measured relative to the headline consumer price index (CPI), and food prices are measured relative to core CPI, or CPI minus food and energy prices. Thus, we are examining the relative inflation of food, corn and oil to the overall inflation rate in the U.S. economy.

The correlation between real oil and corn prices is 0.61. Food prices increased more steadily over the period, experiencing a few large jumps in prices in 2009 and 2015. The contemporaneous correlation coefficient between food and oil is actually negative, but the lagged correlation reveals that pass-through to food prices occurs around one year after an oil price increase.

Additional Research on Oil Price Pass-Through

Baumeister and Kilian estimated an econometric model on data similar to that in the graph and evaluated whether oil prices pass through to corn and, thus, to food prices. They found that if oil increases 1 percent in January, for example, that increase would be followed by several small increases in the price of corn. The largest of these corn price increases would be 0.5 percent, and it would occur one year after the initial oil price increase. Real retail food prices also responded positively to the increase in oil prices, but peaked at 0.05 percent.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that if there is any link between increased food and oil prices, it is extremely small. Even after increased use of ethanol in oil, the evidence for pass-through is weak. Baumeister and Kilian pointed out that agricultural inputs are only about 20 percent of the cost share of U.S. food production, which partially explains the small reaction in food prices to increases in oil prices.

Moreover, while the story of increased interconnectedness between corn and oil after the change in U.S. energy policy makes sense on the surface, further examination reveals there are other possible causes of high correlation, and careful econometrics yield little support for the story.

Notes and References

1 Baumeister, Christiane; and Kilian, Lutz. “Do Oil Price Increases Cause Higher Food Prices?” Economic Policy, October 2014, Vol. 29, Issue 80, pp. 691-747.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Consumer Surveys, Inflation Expectations and the FOMC

- On the Economy: Why Do Gas Prices Cycle in the Midwest?

- On the Economy: Should Core Inflation Be Measured Differently?

Citation

Michael T. Owyang and Hannah Shell, ldquoDo Rises in Oil Prices Mean Rises in Food Prices?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 24, 2016.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions