Labor Market Opportunities for Black Men: How Good Is the News?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

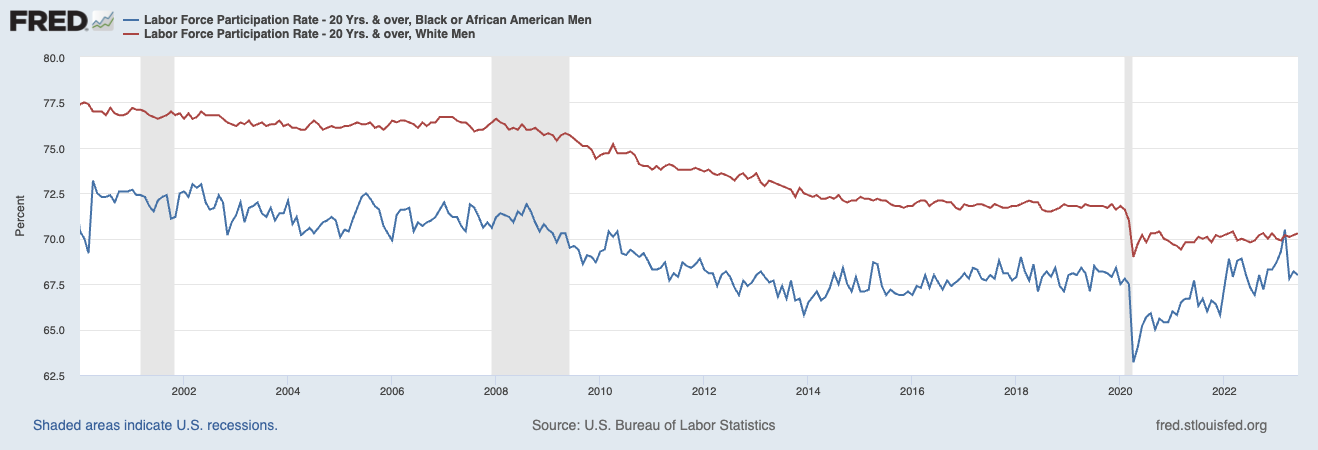

- Tight labor markets have helped erode structural barriers to employment that vulnerable workers face, with the labor force participation rates of Black men and white men starting to converge.

- Focusing only on labor force participation overstates the recent success that Black men have had in joining the workforce; employment-to-population ratio is a more inclusive metric.

- The employment-to-population ratio for Black men fell in April, May and June 2023. If macroeconomic growth continues slowing, gains won by Black men could diminish quickly.

A broad set of “vulnerable” workersThe St. Louis Fed’s Institute for Economic Equity defines vulnerable workers as including (but not limited to) young adults (ages 16 to 24); adults with a high school diploma and no college education; men and women who are Black, Latino, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native; people with a disability; and LGBTQ+ adults. A primary purpose of the Institute for Economic Equity’s vulnerable worker research is to monitor and describe economic outcomes for such groups. face significant structural challenges to compete in the economy. These workers have less successful labor market outcomes than their peers and are more sensitive to economic downturns, such as the one that followed the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this article, we focus on the recent labor market experiences of one such group of vulnerable workers: Black men. Black men can be viewed as the “canary in the coal mine”; their economic outcomes tend to be weaker than their white male peers and more sensitive to changes in the macroeconomy. Record low unemployment rates among Black Americans and the convergence between the labor force participation rates of Black men and white men have been widely cited as evidence of having achieved a significant milestone. And while these gains certainly are encouraging, our analysis suggests that they should be viewed with a note of caution.

A Little Bit of Background

Research has found that low local unemployment rates must be sustained over a period of time for Black men to experience absolute and relative employment gains.See Freeman and Rodgers (2000). Tight labor market conditions help erode structural barriers to employment that Black men face, such as contact with the criminal justice system, access to transportation, mental health, child support arrears and discrimination, to name a few.

Thus, given the recent period of extraordinarily low national jobless rates (the jobless rate has been at or below 5% for 22 consecutive months), the drop in the Black unemployment rate and convergence in the labor force participation rates of Black men and white men (which can be observed in the FRED chart below) are not surprising. But they are not the full story, either.

Cautionary Note No. 1: The Labor Force Participation Rate Has Limitations

The labor force participation rate is the share of the civilian population that is either employed or unemployed but actively searched for a job over the previous four weeks. It does not include incarcerated individuals. In 2021, Black men had the highest imprisonment rates in state and federal institutions across race/ethnicity and gender; about 1 in 55 Black men in the U.S. were incarcerated. When the widespread effects of incarceration are included, the relative position of Black men’s labor force participation falls to where it was in 1950.See Bayer and Charles (2016).

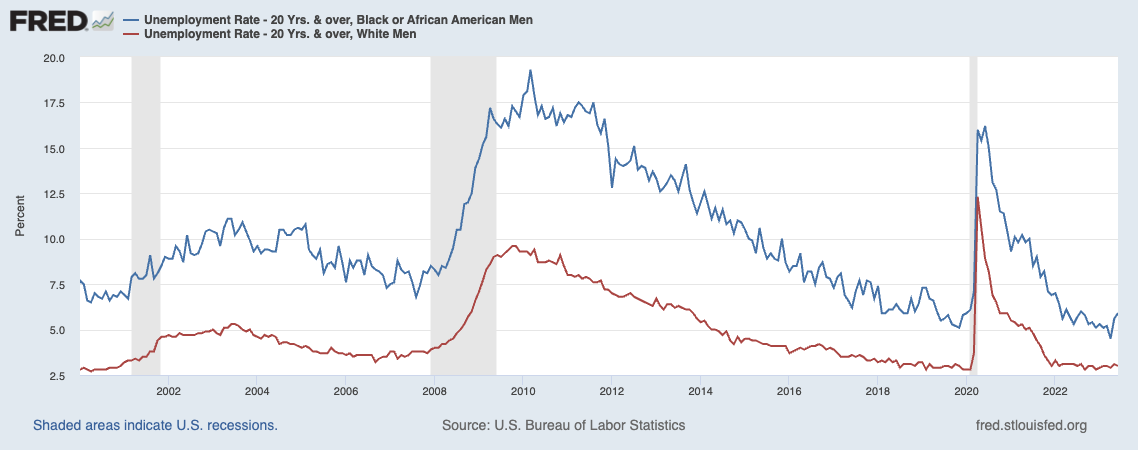

Further, the labor force participation rate does not capture how difficult it is to find a job. The measure of job search difficulty is the unemployment rate, which is the proportion of unemployed as a share of the labor force (the labor force is the sum of the employed and unemployed job searchers). As the following FRED chart shows, the unemployment rate for white men has been below 5% since July 2021, while the unemployment rate for Black men only fell below 5% in April 2023—to a record low of 4.5%—before rising again to 5.9% in June.

Even though the labor force participation rates of Black men and white men are converging (see the first figure), the unemployment rate for Black men is still nearly twice that of white men. Focusing solely on the labor force participation rate overstates the recent success Black men have had in joining the workforce.

The employment-to-population ratio is a better indicator of the ease with which a person can find a job. It captures both how difficult the job search process is and the decision to join the labor force, incorporating some key considerations—such as one’s access to child care and transportation, physical or mental health status, and involvement with the criminal justice system—that the labor force participation rate does not fully reflect. The good news: Employment-to-population ratios, too, show hiring conditions for Black men converging toward those for white men since the pandemic.

Cautionary Note No. 2: The Convergence Is Partly Due to Slower Recovery in White Men’s Employment-to-Population Ratio

The employment-to-population ratios for many groups have increased since their pandemic lows, but not all have returned to their February 2020 levels. For example, the June 2023 employment-to-population ratio for white men 16 or older was 66%, 1.4 percentage points below its February 2020 level of 67.4%.

In comparison, the June 2023 employment-to-population ratio for Black men 16 or older was 60.8%, 0.4 percentage points higher than its February 2020 level of 60.4%. Even so, Black men’s employment-to-population ratio was still well below that of their white peers.

If convergence is viewed as success, it would be far better for it to occur with labor market conditions for both white men and Black men on the rise rather than because labor market conditions for white men were worsening.

Cautionary Note No. 3: Labor Market Tightness Helped Create Conditions for the Convergence

Why have labor market conditions and employment opportunities for Black men improved since the start of the pandemic? One potential reason for convergence in the employment-to-population ratios of Black men and white men has been the extremely tight U.S. labor market that emerged after April 2020. A decline in the overall unemployment rate has been shown to have an even greater positive impact for Black men. Tight labor markets particularly benefit groups that face structural barriers to employment.

Due to such barriers, vulnerable workers tend to be at the end of the job queue, and employers may only consider them viable candidates during periods when workers are in short supply.

Periods of labor market tightness, such as the one we are in now, force employers to modify their hiring models by broadening their hiring criteria. Vulnerable groups may benefit as a result, particularly those with lower educational attainment and weaker skills, those who face structural barriers (such as around access to transportation or child care), or those who experience discrimination due to race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or a disability.

Another reason for this convergence is rising wages, including state minimum wages. Rising minimum wages tend to disproportionately benefit Black men. In the last three years, beginning even before the recent surge in inflation, nearly 30 states have increased their minimum wage. Higher minimum wages improve the wage offers that all workers receive, especially those in vulnerable groups, who are more likely to earn the minimum wage or near it. As wage offers rise, they surpass an increasing number of vulnerable workers’ asking wage, making it possible for them to overcome hurdles like transportation and child care costs, enter the labor market, and accept a wage offer.

Finally, population shifts over the pandemic (people moving out of areas, leaving opportunities for those who stay behind) could have created more opportunities for Black men.

However, the benefits of this extremely tight labor market are starting to lessen. Out-of-school young adults, especially Black men, are beginning to see their job prospects weaken. If the economy continues slowing down, their job prospects could weaken further.

Cautionary Note No. 4: Black Men’s Employment-to-Population Ratio Fell in April, May and June

The employment-to-population ratio of Black men has fallen 2.9 percentage points over the last three months, to 60.8% in June 2023. Estimates can vary from month to month, but this decline occurred amid signs that labor markets are slowing.

For example, in May 2023, there were 9.8 million job openings and a job openings rate of 5.9%. This compares with 11.4 million job openings and a job openings rate of 7% in May 2022. Additionally, in May 2023, the number of hires and the hiring rate were 6.2 million and 4%, respectively, compared with 6.5 million and 4.3%, respectively, a year earlier. These measures indicate declining labor demand and job-matching prospects. Past research has shown that Black men are among the first to lose their jobs when the economy slows.

Cautionary Note No. 5: Labor Force Participation Does Not Capture Racial Pay Gaps

Labor market statistics like the labor force participation rate, employment-to-population ratio and unemployment rate tell us about labor supply, but not pay. Low pay is a reason for nonparticipation in the labor force, and rising wages can incentivize people to enter the labor market and search for a job. The ratio of Black men’s median weekly wage to white men’s median weekly wage averaged 75% from the first quarter of 2007 through the first quarter of 2023, when it was 74%. Thus, the wage gap between white men and Black men remains, despite the tight labor market and improved employment opportunities for Black men.

Overall Assessment: Gains Could Diminish Quickly

The good news is that economic growth has been associated with convergence in the employment opportunities of Black workers and white workers; however, this convergence did not start until what appears to be late in the economic expansion. Macroeconomic growth has slowed, and if it continues to weaken, the gains won by Black men and other vulnerable groups could diminish quickly.

Notes

- The St. Louis Fed’s Institute for Economic Equity defines vulnerable workers as including (but not limited to) young adults (ages 16 to 24); adults with a high school diploma and no college education; men and women who are Black, Latino, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native; people with a disability; and LGBTQ+ adults. A primary purpose of the Institute for Economic Equity’s vulnerable worker research is to monitor and describe economic outcomes for such groups.

- See Freeman and Rodgers (2000).

- See Bayer and Charles (2016).

References

Bayer, Patrick and Charles, Kerwin K. “Divergent Paths: Structural Change, Economic Rank, and the Evolution of Black-White Earnings Differences, 1940-2014 (PDF).” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22797, 2016.

Carson, E. Ann. Prisoners in 2021—Statistical Tables (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, 2022.

Charles, Kerwin K. and Guryan, Jonathan. “Studying Discrimination: Fundamental Challenges and Recent Progress (PDF).” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17156, 2011.

Cherry, Robert and Rodgers III, William M. “Introduction” in Cherry, R. and Rodgers III, W. M., eds., Prosperity for All? The Economic Boom and African Americans, 2000. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

Freeman, Richard B. and Rodgers III, Willam M. “Area Economic Conditions and the Labor Market Outcomes of Young Men in the 1990s Expansion” in Cherry, R. and Rodgers III, W. M., eds., Prosperity for All? The Economic Boom and African Americans. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

Reimers, Cordelia W. “The Effect of Tighter Labor Markets on Unemployment of Hispanics and African Americans: The 1990s Experience,” in Cherry, R. and Rodgers III, W. M., eds., Prosperity for All? The Economic Boom and African Americans. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

Rodgers III, William M. “Understanding the Cases for Economic Equity.” St. Louis Fed On the Economy Blog, March 7, 2023.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us