Health, Wealth and Education: Is There a Link for Countries?

Education is often linked to greater wealth, and greater wealth is often linked to better health.

But while low-income countries have made progress on health outcomes and educational attainment, their economic outcomes haven’t improved as much as you might expect.

Averages for life expectancy and years of schooling for people in low-income countries have grown over the last few decades, and the gaps with wealthier countries have narrowed on those dimensions. But the low-income countries’ economies haven’t done as well in catching up. Those comparisons were made in two blog posts and an article featuring the research of Guillaume Vandenbroucke, a St. Louis Fed research officer and economist.

An important note: The time periods discussed end before COVID-19 reached worldwide public health emergency status in 2020, and don’t reflect data related to the pandemic.

Life Expectancy Gains Outpace GDP Growth

Life expectancy at birth is often used as an indicator of health, measuring “how long, on average, a newborn can expect to live, if current death rates do not change,” according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD.

By that measure, low-income countries had been catching up to their wealthier counterparts, said a May 10 FRED Blog post suggested by Vandenbroucke.

World Bank data show that in 1982, life expectancy in low-income countries was about 66% of that in high-income countries. By 2018, it was 78%, the post said. In the post, the change is illustrated along with the change in real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in a chart, shown below, from the St. Louis Fed’s economic database FRED. (Real GDP is the total market value of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a year, adjusted for inflation.)

“This rising longevity, especially in relation to longevity in high-income countries, is remarkable because it doesn’t coincide with an improvement in relative economic performance,” the post said. “In 1982, real GDP per capita in poor countries was 2.8% of what it was in rich countries. In 2018, it was 1.8%.”

Link between GDP and Life Expectancy Declines Steadily

Individual countries’ changes reflect the general conclusion from the FRED graph that there is a disconnect between life expectancy and economic performance, according to the post. Across individual countries, the link between life expectancy and GDP per capita “has been steadily declining since the 1960s,” the post said. (The post cited a working paper on technology and mortality that Vandenbroucke wrote with economists B. Ravikumar of the St. Louis Fed and John Hejkal.)

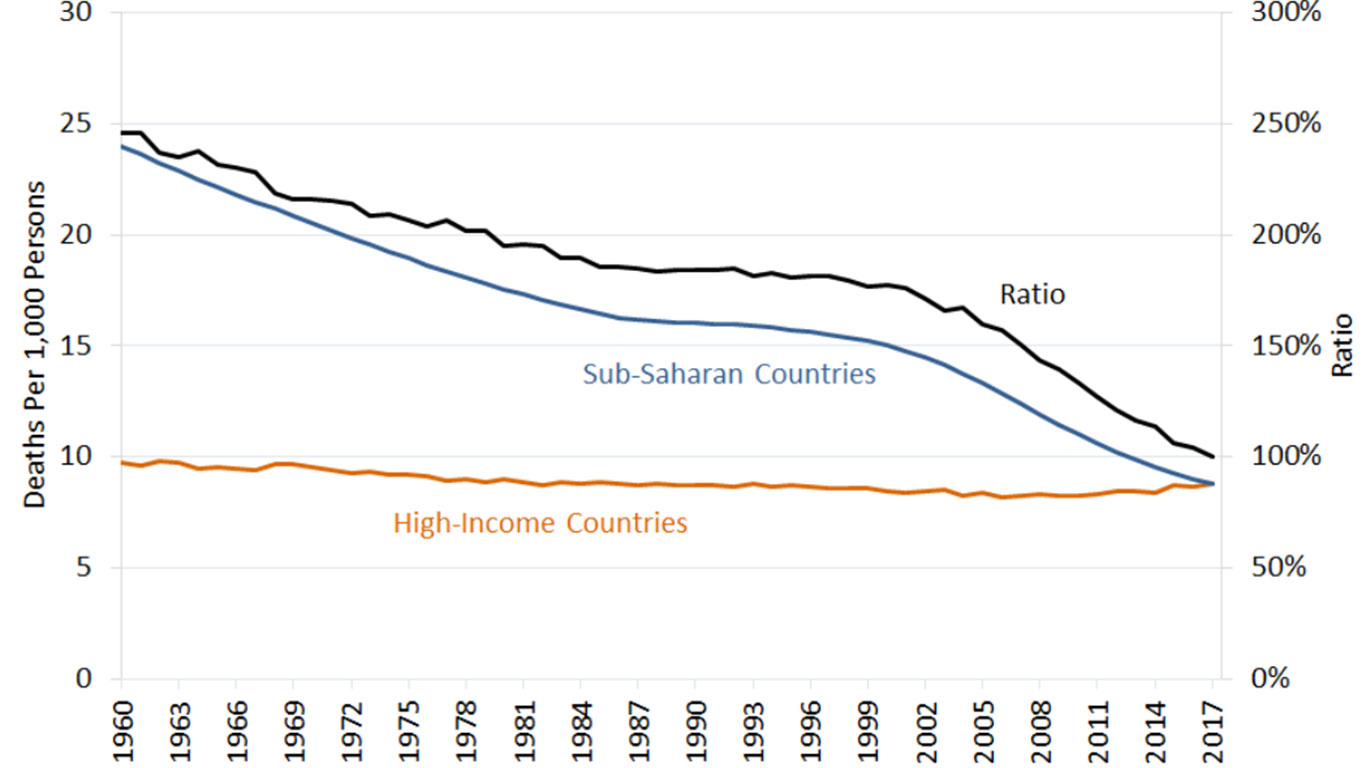

Vandenbroucke outlined a similar pattern for a particular group—low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa—in a Dec. 26, 2019, On the Economy blog post.

In terms of GDP, sub-Saharan Africa lost ground to countries described as “high-income” by the World Bank, with the sub-Saharan group going from 9% of the rich countries’ real GDP per capita in 1960 to 4% in 2017.

“This does not imply that sub-Saharan Africa is not growing,” Vandenbroucke said in the post. “It simply means that it grows at a slower pace than the rich countries in addition to being poor.”

But over the same pre-pandemic time period, the sub-Saharan African countries narrowed the gap with wealthier ones on life expectancy and caught up to the wealthier countries with a declining rate on another health measure, the “crude death rate,” which is the number of deaths per 1,000 people.

Sub-Saharan African Countries’ Death Rate Has Declined since 1960

SOURCES: The chart is from a Dec. 26, 2019, On the Economy blog post: “Healthier Countries, if Not Wealthier Countries,” by Guillaume Vandenbroucke. The data are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

NOTES: High-income countries are those that had a GDP per capita of at least $12,376 in 2018. Sub-Saharan African countries exclude those qualifying as high-income countries. The ratio divides sub-Saharan deaths per 1,000 people by high-income country deaths per 1,000 people.

DESCRIPTION: The chart shows deaths per 1,000 people from 1960 to 2017 for sub-Saharan African countries and high-income countries. It starts with a ratio of nearly 250% of sub-Saharan African countries’ deaths to high-income countries’ deaths in 1960, at nearly 25 compared with 10. The rate for the sub-Saharan African countries declined to the same rate as high-income countries’ at fewer than 10 per 1,000 people in 2017.

So, if relatively healthier economies weren’t the reason for low-income countries’ relatively healthier people pre-pandemic, what is?

One view is that relatively cheap practices, such as hygiene awareness and vaccination campaigns, help reduce mortality, Vandenbroucke wrote.

Education Outstrips Economic Growth

Poor countries also have been gaining on rich countries in education, according to a June 2020 Regional Economist article written by Vandenbroucke and Makenzie Peake, who was then a research associate at the St. Louis Fed.

“Education is often associated with economic performance; that is, the most educated people tend to earn higher paychecks than the least educated,” the authors wrote. “This is also true for countries: Rich countries tend to have the most educated workforces. In addition, the educational attainment of a country’s population tends to grow along with its economy.”

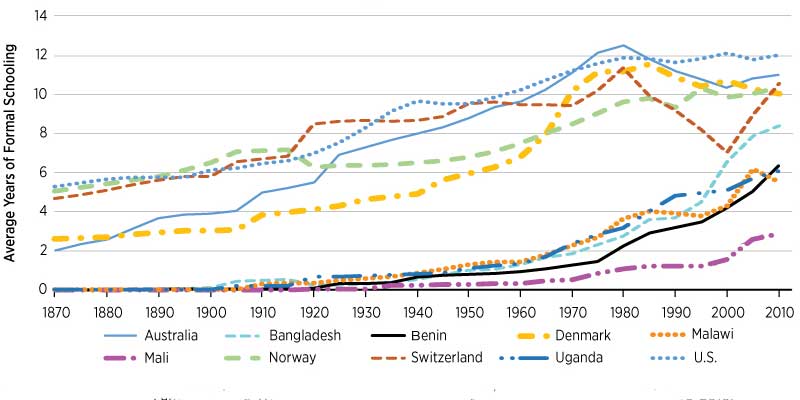

Poorer Countries Gained on Wealthier Countries in Education

SOURCES: The chart is from a June 2020 Regional Economist article, “Poor Countries Catching Rich Countries in Education, but Not Income,” by Guillaume Vandenbroucke and Makenzie Peake. Data are from a September 2013 research paper in the Journal of Development Economics, “A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010,” by Robert J. Barro and Jong-Wha Lee.

DESCRIPTION: The chart shows the average years of formal schooling for people 25 and older in 10 countries from 1870 to 2010, with four of the five poorer countries gaining on the wealthier countries after 1960. The highest average in 2010 is about 12 years, for the U.S. Among the poorer countries, Bangladesh attained an average of over eight years by 2010.

The researchers looked at data for residents 25 and older from five high-income and five low-income countries from 1870 to 2010 and found all gained in formal schooling. The poorer countries in the sample are Bangladesh, Benin, Malawi, Mali and Uganda. The richer countries are Australia, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland and the U.S.

With the exception of Mali, all of the poorer countries started making big advances in educational attainment in the mid-20th century, narrowing the gap with the richer countries, the authors found. Bangladesh’s more than eight years on average by 2010 compared with Denmark’s and Norway’s 10, for example. But when it comes to real GDP per capita, the poorer countries were not catching up to the richer countries. That said, the poorer countries were becoming richer, just not as quickly on average as the richer countries, so they were getting “relatively poorer,” the article said.

Poorer countries need to grow at a higher rate than the richer countries for income to converge, the authors wrote.

“If more schooling helps produce greater income, then why are poor countries not richer? Answering such a question may be of relevance to policymakers interested in aiding poor countries,” the authors wrote.

For example, policies that support building schools can help with educational attainment, but the data indicate that they “do not seem to effectively generate economic takeoff as well.”

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us