Poor Countries Catching Rich Countries in Education, but Not Income

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Richer countries tend to have more highly educated populations.

- Poorer countries are catching up to richer countries in terms of education for people age 25 and older.

- The narrowing gap in education between poorer countries and richer countries hasn’t translated to poorer countries catching up in economic performance.

Education is often associated with economic performance; that is, the most educated people tend to earn higher paychecks than the least educated. This is also true for countries: Rich countries tend to have the most educated workforces. In addition, the educational attainment of a country’s population tends to grow along with its economy.

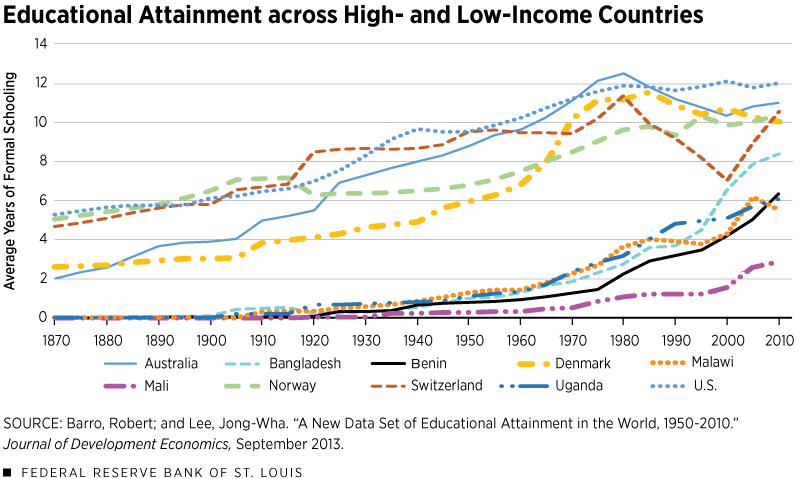

In this article, we take a closer look at the evolution of educational attainment across countries and over time. We start with Figure 1, which shows the average years of schooling among populations in selected countries. Years of schooling are available from the work of Robert Barro and Jong-Wha Lee and measure the average number of years of formal schooling for people 25 years and older.See Barro and Lee.

Education Levels among Rich and Poor Countries

The countries we chose here are a mix of rich (Australia, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland and the U.S.) and poor (Bangladesh, Benin, Malawi, Mali and Uganda).The list of countries we consider in this article is arbitrary. This is because our findings are better illustrated with a short list of countries and graphics as opposed to a long list of countries. Economists Diego Restuccia and Guillaume Vandenbroucke considered a list of 84 countries and documented the same facts that we document here. They organized countries by income decile in 1950, and show that (1) countries in poor deciles in 1950 tend to not converge to the income of countries in rich deciles in 1950, and (2) they do converge in terms of schooling. This illustrates two key messages:

- Years of schooling increased in every country.

- Rich countries have been enjoying higher levels of education for a long time, but the poor countries are catching up. In other words, schooling increases faster in poor countries than it does in rich countries.

The U.S., Switzerland and Norway had the highest years of schooling in 1870 at around five years. (To be precise, this means that the average person age 25 or older in the U.S. in 1870 had gone through five years of formal schooling.) Australia and Denmark were next at just over an average of two years.

All low-income countries in our sample averaged nearly zero years of schooling in 1870. However, in the mid-20th century, years of schooling accelerated. By 2010, for example, average years of schooling for Bangladesh (over eight years) nearly reached that of Denmark and Norway (10 years). Malawi, Benin and Uganda reached about six years of schooling by 2010.

It is worth noting here that some low-income countries have experienced minimal growth in education, along with minimal growth in income. For example, Mali barely averaged three years of schooling per resident 25 years or older in 2010, making it the least educated country in our sample.

Economic Levels among Rich and Poor Countries

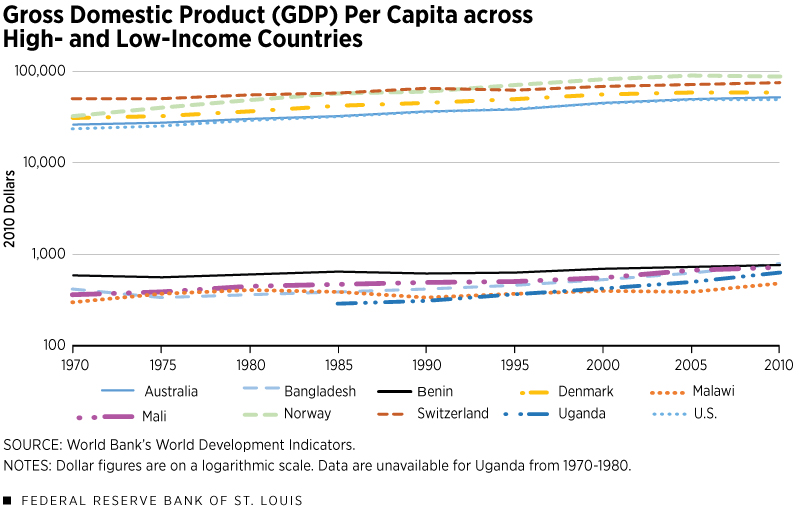

Turn now to Figure 2, which shows real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for the same group of countries (measured in 2010 dollars).Note the logarithmic scale on the vertical axis. If not for this scaling, GDP per capita in poor countries would be difficult to distinguish from zero in comparison with GDP per capita for rich countries.

Even though GDP per capita increased in all countries—just as schooling increased in all countries—the message is quite different from what is seen in Figure 1: Poor countries are not catching up to the rich countries in terms of income.

For example, consider the U.S. and Benin. Between 1970 and 2010, GDP per capita in the U.S. more than doubled, while GDP per capita in Benin increased only 30%. Since Benin’s GDP per capita in 1970 was $582 (versus $23,207 for the U.S.), one concludes that Benin actually lost ground relative to the U.S. despite the growth it experienced. Put another way: Benin’s GDP per capita was 2.5% of U.S. GDP per capita in 1970. In 2010, Benin’s GDP per capita had fallen to 1.6% of that of the U.S.

Poor Countries Get Richer, Just More Slowly than Rich Countries

One interpretation of Figures 1 and 2 is as follows. Consider productivity growth, which is generally viewed as being an important determinant of GDP growth while also being determined by the level of education of a country's population.

The latter view—that is, education can enhance productivity—is the basis for the belief that building schools in poor countries will help productivity growth and thus income convergence. Figures 1 and 2, however, indicate that the link from productivity to growth may be stronger than the link from education to productivity.

The lack of income convergence between rich and poor countries has been noted before, and a vast literature has been devoted to understanding its causes. It is not the purpose of this article to survey this literature.

It is important, however, to reiterate the observation: Poor countries are indeed growing. In absolute terms, they are becoming richer. On average, however, they are growing at lower rates than rich countries. Therefore, they are getting relatively poorer. For income convergence to occur, poor countries should grow at a higher rate than the rich countries.

Taken together, Figures 1 and 2 offer a challenge: Why are poor countries converging to the rich in terms of schooling but not income? If more schooling helps produce greater income, then why are poor countries not richer?

Answering such a question may be of relevance to policymakers interested in aiding poor countries. Think, in particular, about policies based on the assumption that building schools in poor countries may be a way to help economic takeoff. Figures 1 and 2 indicate that such policies can indeed enhance educational attainment but do not seem to effectively generate economic takeoff as well.

Endnotes

- See Barro and Lee.

- The list of countries we consider in this article is arbitrary. This is because our findings are better illustrated with a short list of countries and graphics as opposed to a long list of countries. Economists Diego Restuccia and Guillaume Vandenbroucke considered a list of 84 countries and documented the same facts that we document here. They organized countries by income decile in 1950, and show that (1) countries in poor deciles in 1950 tend to not converge to the income of countries in rich deciles in 1950, and (2) they do converge in terms of schooling.

- Note the logarithmic scale on the vertical axis. If not for this scaling, GDP per capita in poor countries would be difficult to distinguish from zero in comparison with GDP per capita for rich countries.

References

Barro, Robert; and Lee, Jong-Wha. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010.” Journal of Development Economics, September 2013, Vol. 104, pp. 184-98.

Restuccia, Diego; and Vandenbroucke, Guillaume. “Explaining Educational Attainment across Countries and over Time.” Review of Economic Dynamics, October 2014, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 824-41.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us