Healthier Countries, if Not Wealthier Countries

The income gap between rich and poor countries doesn’t seem to be closing. In fact, it seems to be getting wider. However, the gaps between these groups of countries when it comes to health may indeed be narrowing.

Sub-Saharan African Wealth

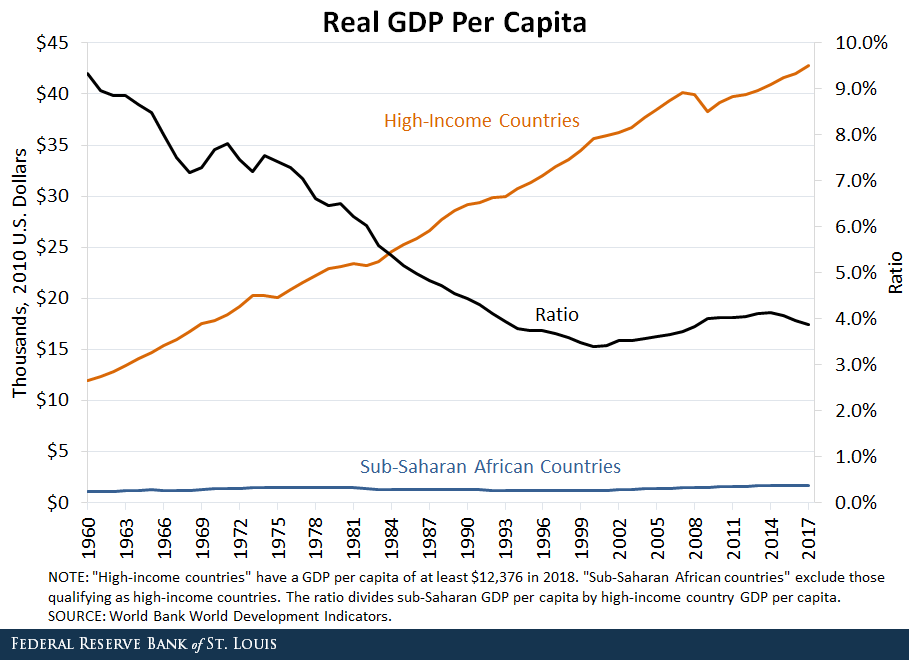

The figure below shows the real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in what the World Bank describes as “high-income countries.” These are countries with a gross national income per capita of no less than $12,376 in 2018. The figure also shows the real GDP per capita of sub-Saharan African countries (excluding those countries qualifying as high income). The ratio of the two colored lines is represented by the black line.

The message is simple: Sub-Saharan Africa is not catching up to the rich countries. In fact, it is losing ground:

- In 1960, its GDP per capita was 9% that of the rich countries.

- In 2017, it was 4%.

This does not imply that sub-Saharan Africa is not growing. It simply means that it grows at a slower pace than the rich countries in addition to being poor.

Sub-Saharan African Health

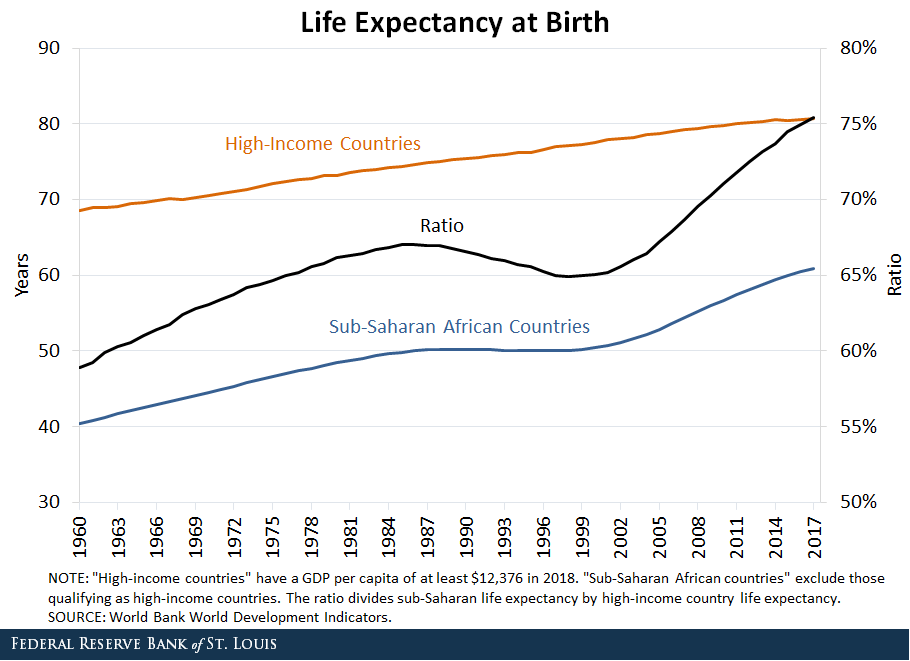

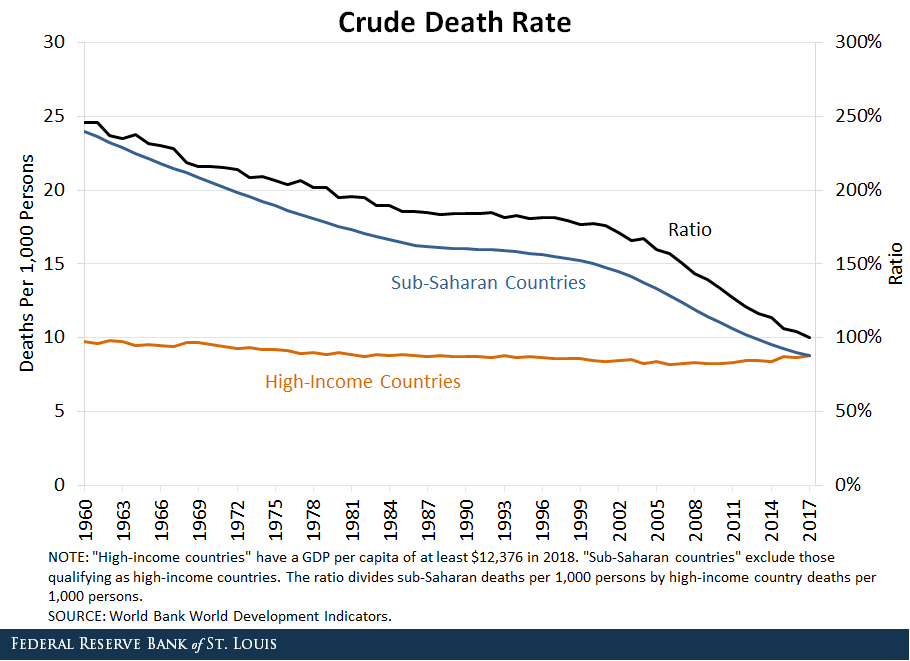

The next two figures show life expectancy at birth and the crude death rate—or number of deaths per 1,000 people—for the same two groups of countries.

Not surprisingly, sub-Saharan African countries exhibit a lower life expectancy at birth and a higher crude death rate than the high-income countries. What is surprising, however, is that these measures of health are converging to that of the rich countries, unlike GDP per capita.

This is most noticeable for the crude death rate. In 1960, the rate in sub-Saharan countries was more than double that of the high-income countries. It then declined remarkably faster than in the high-income countries, which experienced a barely noticeable decline. By 2017, the crude death rate was the same in both groups of countries.

There is convergence in life expectancy at birth as well, albeit it is less spectacular:

- In 1960, life expectancy at birth in sub-Saharan Africa was about 59% that of the high-income countries.

- In 2017, it was 75%.

Thus, the life expectancy of the poor is catching up to that of the rich.

The Connection between Health and Wealth

A few conclusions can be drawn from these observations:

- Improvement in health can occur with little (or at least slow) improvements in income.

- The correlation between income and health does not seem stable: One or two hundred years ago—when some countries now considered high-income were as poor as sub-Saharan Africa is today—their crude death rate was much higher than what it is today for both them and sub-Saharan Africa.

Literature exists indicating that this is not a new phenomenon: Mortality—in particular infant mortality—started to decline in England before the onset of the Industrial Revolution and the take off toward modern growth.

One view is that there are practices—such as awareness of the importance of cleanliness—that help reduce mortality at low cost. Vaccination campaigns by the World Health Organization can be viewed as relatively cheap as well and very effective.

There exist, of course, medical technologies and treatment that can save lives at very high costs. These, however, do not seem to be the main drivers behind the increase in life expectancy and the decrease in mortality when countries are poor.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: US Health Care and Future Job Growth

- On the Economy: Health Care Affordability Gap Widens between the Rich and the Poor

Citation

Guillaume Vandenbroucke, ldquoHealthier Countries, if Not Wealthier Countries,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Dec. 26, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions