"I'm Cheap": How an Economist Who Studies Debt Handles Spending

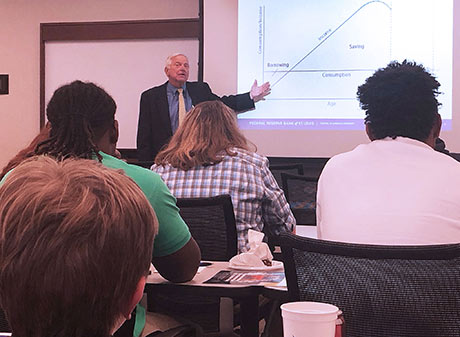

St. Louis Fed Economist Don Schlagenhauf explains the life cycle of household saving and consumption to students.

Early this year, St. Louis Fed economist Don Schlagenhauf spoke to a roomful of high school students at our Branch in Little Rock, Ark.

They wanted to know how much debt is too much.

Schlagenhauf, whose research focuses include consumer debt, would seem to be in a good position to tell them. What did he say?

“There is no one answer to that question.”

In other words, consumers have to answer it for themselves depending on where they are in life, what type of income and resources they have, and what type of debt it is.

I spoke with Schlagenhauf after his talk to find out what consumers should consider when it comes to taking on debt. He also shared how he has answered the question for himself—how much debt is too much?—in paying for college, homes, cars and credit card debt.

Debt and Your Place in the Life Cycle of Saving and Consumption

Heather Hennerich: You had an experience recently where you were talking to high school students. What did you tell them about debt and whether it’s good or bad?

Don Schlagenhauf: I explained to them that debt isn’t necessarily bad. It’s only bad if you can’t repay it, was my first point. Then my second point was, you have to think about where you are in your life cycle.

It’s clear that when you’re very young—and perhaps you just got married and you want a house—you’re not going to be able to save for that house. You’re going to have to take on some debt.

So when you’re young, we usually think of the fact that your debt may be higher than your income in order to have a decent level of consumption. But as you get older, in middle age—well, there’s a situation where your income is growing, and you’d better be able to pay off prior debt when you’re young, but also look forward to when you’re older and you’re not making anything.

You still have to eat when you’re old and retired. So, you need to be able to have savings going into that last part of your life cycle to survive. I used that simple picture to explain the idea.

The question isn’t simply, is debt always bad? The answer is no. Economists say it’s bad if you can’t repay it over your life.

Paying for College by Building Swimming Pools

Heather: If I’m an 18-year-old high school student, how do I know that I’m going to be able to repay debts by the end of my life? How do I figure that out?

Don: We talked a little bit about this at the Little Rock event. How much debt should I take on for college? My reaction was, you need that college education, but you have to take on as little as debt as possible. Maybe in the summer, you have a very good, high-paying summer job.

We talked a lot about that issue, “What can I do?” And—they didn’t like this—I said, “One possibility, what my parents had me do, was I had to live at home if I wanted to go to college, because they had four more children coming down the line. My parents said, ‘We can’t afford for you to go away to school.’”

That affected my college experience, but I got a college degree.

Heather: How did you afford college?

Don: Maybe back then it was a little different than now, but I decided that I wanted to go into construction because that seemed to be a high-paying job. I built swimming pools.

As I learned more about this idea of how you build swimming pools, I decided a good way to do this summer job was to get two of my good, hard-working friends together, and we would contract with swimming pool builders and build their pools for them.

We worked seven days a week, long hours, but we made a pretty good income. I didn’t have to worry about financing my college education or my graduate school years because I was able to accumulate savings from that job.

Heather: A part of that equation also was that you were living at home, I suppose?

Don: Oh, yes. I was freeloading.

Paying Off Debt ASAP

Heather: Did your father give you any advice on debt and personal finance that you still follow?

Don: That’s a funny question. I don’t know if he ever gave me any advice, but he was really cheap. So now my friends tell me, “Oh, you learned from your father. You’re really cheap, too.”

Heather: Is some of that coming into play from your economics background, as well? How do you run your life with debt?

Don: I think of that life cycle model of consumption and spending we started talking about. It’s clear that I had to take a mortgage out to buy a home. But other than that, I want to pay off any debt I have as soon as possible.

For an auto, I just saved for it and then bought it. I still do that. I don’t take an auto loan.

Heather: How about on credit cards?

Don: I pay them off right away.

Heather: Wow.

Don: I said I’m cheap.

How Much to Spend on Mortgages

Heather: You’re going to have to go into debt as a young person for school, but you also have to go into debt for—not too many people are able to save up for a home.

As you mentioned, you had to take a mortgage out. So how much should you be taking out as a mortgage? Are there any good rules of thumb?

Don: My problem with “rules” is that it depends on the individual.

For example, I was a college professor when I bought my first home. One thing I knew about my situation was that I had at least seven years there. I had a pretty stable income. It wasn’t going to grow at a great rate, but it was going to increase 2% or 3% a year. I knew I had some wiggle room to go in, buy a home, take a mortgage, have a nice house, and not be strapped for cash.

On the other hand, if I worked construction for my living, I knew that during the wintertime I may not have a job. You’re not building swimming pools in December. So there’d be no income flow. That uncertainty about your income flow would force me to make different decisions on how big of a mortgage I’d want to take on.

Are Some Types of Debt More Worthwhile?

Heather: One of those rules of thumb that we were talking about was this one I found online that mortgage lenders use, which is 28/36.

It says a household should spend, at most, 28% of its gross monthly income on total housing expenses, and no more than 36% on all debt service, which would include car loans, credit cards, that sort of thing.

Does that make sense most of the time?

Don: That’s a hard question. I don’t know exactly what your income is, right? I don’t know how variable it is. So it depends on what type of car. Are you buying a new car? Are you buying an SUV? Are you buying a car that’s being resold? The price of that car varies, and there will be debt associated.

Clearly, the lower the price of the auto or the SUV, the less debt you have to take out. That means there is less risk there.

Heather: Are some types of debt or credit better than others? The car’s going to get you to work. Your student loan’s going to get you the college degree that may enable you to make more income. Your house could be an investment. You could also lose money on it. It does have risk to it.

But are there things we just shouldn’t be spending a lot of money on? Lattes and things that are kind of nonessentials?

Don: Again, the answer to that question is, it depends on your income level and where you are in the life cycle.

We all need to have something that’s enjoyable, and consume it. But to go into $100 or $200 of debt because of coffee, that may not be very smart at a certain age.

Additional Resources:

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us