China’s Role in Global Innovation Is Changing

For many years, China was widely viewed as a fast follower, leveraging access to foreign technology, expanding its manufacturing capacity, and competing primarily through cost advantages. While that characterization may have once captured the essence of China’s role in the global economy, it is increasingly incomplete. A growing body of evidence suggests that China is transitioning from technology absorber to innovation leader in its own right.

Across a range of indicators, China is now innovating and exporting technologies in sectors traditionally dominated by advanced economies, including the United States.See Florencia Airaudo, François de Soyres, Alexandre Gaillard and Ana Maria Santacreu’s paper, “Recent Evolutions in the Global Trade System: From Integration to Strategic Realignment (PDF),” presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking 2025 in Sintra, Portugal; François de Soyres, Ece Fisgin, Alexandre Gaillard, Ana Maria Santacreu and Henry L. Young’s article “The Sectoral Evolution of China’s Trade,” FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Feb. 28, 2025; and François de Soyres, Ece Fisgin and Ana Maria Santacreu’s blog post, “Understanding China’s Technological Rise through Patent Data,” St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 3, 2025. This convergence is not merely the result of others moving on to new technologies. Rather, it reflects China’s deliberate and sustained investments in innovation, capabilities and industrial upgrading, part of a broader strategy to position itself as a peer competitor at the global technological frontier.

The Channels Behind China’s Technological Rise

China’s rise in innovation capabilities has been shaped by a combination of informal knowledge diffusion and more formal channels of technology acquisition. In the early 2000s, particularly around the time of its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), joint ventures (JVs) played a central role in this process. Foreign firms, attracted by China’s large and growing domestic market, often entered through partnerships with local firms. These arrangements frequently involved some degree of technology transfer, whether explicit through licensing agreements or implicit through shared operations and personnel.

In this early phase, JVs served as a key conduit for informal diffusion. U.S. and European firms contributed to the rapid upgrading of Chinese manufacturing and technological capabilities, sometimes underestimating the broader and longer-term spillovers that such collaborations would generate.See Jaedo Choi, George Cui, Younghun Shim and Yongseok Shin’s 2025 unpublished paper “The Dynamics of Technology Transfer: Multinational Investment in China and Rising Global Competition (PDF).” The focus at the time was often on short-term market access rather than the cumulative effects of knowledge transfer across the Chinese economy.

Over time, however, this dynamic began to shift. As China reformed its legal and institutional frameworks, especially on intellectual property (IP) protection, domestic firms increasingly turned to formal mechanisms of technology acquisition.

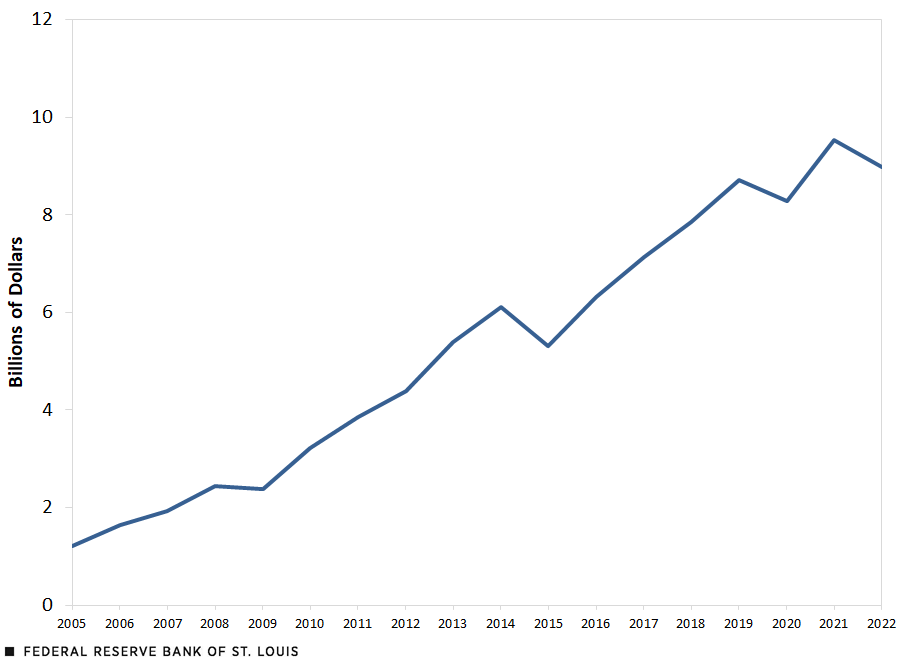

This transition is evident in the growing volume of royalty payments: From just $1.2 billion in 2005, Chinese royalty payments to U.S. entities rose to nearly $9 billion by 2022. This sharp increase reflects not only a greater reliance on formal licensing agreements but also China’s evolving role from passive recipient to active participant in global technology markets.See Ana Maria Santacreu’s 2025 paper, “Dynamic Gains from Trade Agreements with Intellectual Property Provisions,” in the Journal of Political Economy.

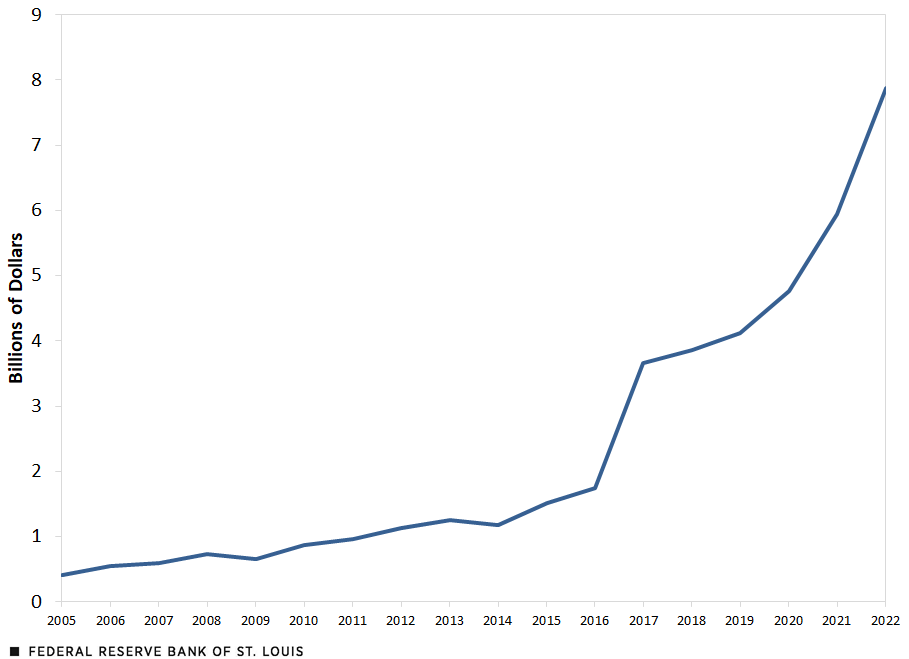

Crucially, China is no longer just paying for technology; it is increasingly being paid. Royalty payments to Chinese firms from the rest of the world rose more than fivefold between 2015 and 2022. While part of this growth likely reflects intrafirm transactions, such as multinationals channeling payments within their corporate networks, it nonetheless points to a structural shift. Valuable intellectual property is now being developed in China.

This evolution is consistent with the country’s strategic push to move beyond its role as a passive technology recipient and become an active licensor of frontier technologies. This is evident in sectors such as artificial intelligence, green technology and advanced manufacturing, where China’s firms are becoming increasingly competitive and, in some cases, globally dominant.

Examining the Flows of Global Royalties

The two figures below illustrate this dramatic change. The first figure shows royalty payments made by China to the U.S., reflecting China’s growing use of foreign technology through formal channels. The second figure shows royalty payments received by China from the rest of the world, which have increased sharply since 2015.

China’s Royalty Payments to the U.S.: 2005-22

Global Royalty Payments to China: 2005-22

SOURCES FOR BOTH FIGURES: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and authors’ calculations.

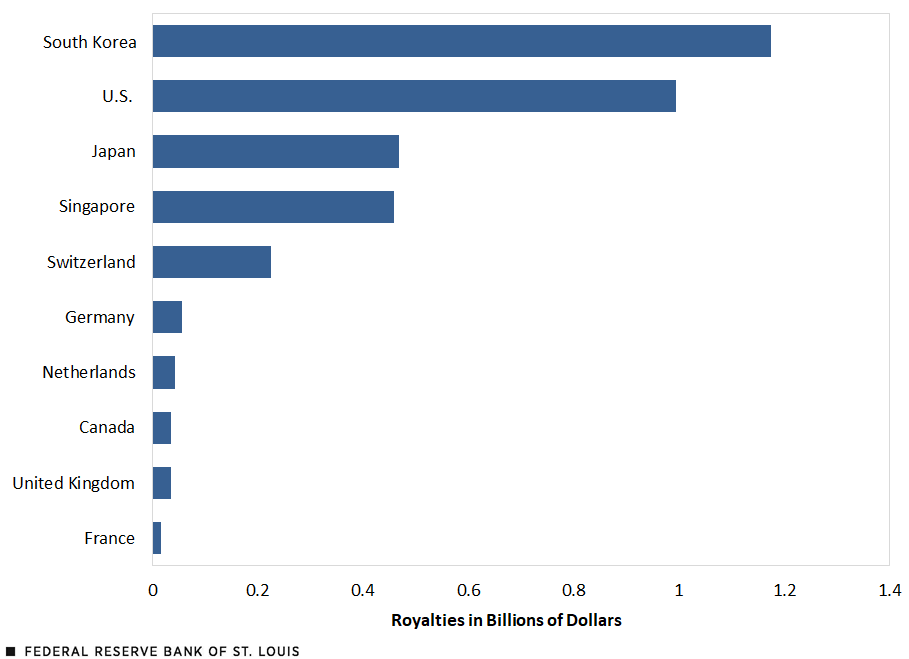

Notably, the countries paying the most royalties to China are advanced economies with well-established innovation ecosystems and world-leading firms. (See the figure below.) The fact that these countries are among the top sources of royalty payments to Chinese entities suggests that this is not simply about tax engineering or intrafirm flows. Rather, it points to genuine and growing demand for intellectual property that is being developed, owned, or commercialized by Chinese firms.

Top 10 Countries Paying the Most to China for the Use of Intellectual Property in 2022

SOURCES: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and authors’ calculations.

In 2022, South Korea led the list of royalty payers to China, followed closely by the U.S., Japan and Singapore. Payments also came from Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and other technologically sophisticated economies. While some of these transactions may reflect internal corporate transfers within multinationals, the breadth and composition of the countries involved, including both Western and Asian innovation leaders, indicate that Chinese technologies are increasingly being licensed across a diverse set of global markets.

This trend underscores a broader structural shift. China is no longer just acquiring and applying foreign technology; it is starting to export it through formal licensing arrangements. The emergence of China as a source of licensable technology, particularly in fields such as artificial intelligence, green energy, advanced manufacturing and telecommunications, signals a move up the global value chain. It also reflects that Chinese firms are moving from passive recipients of innovation to active contributors shaping the direction of technological progress.

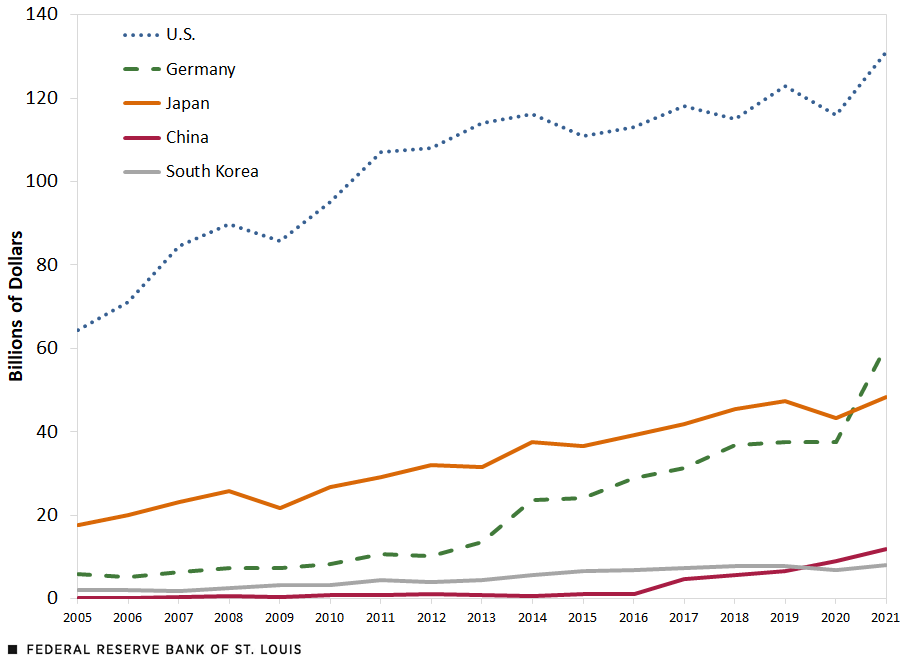

To place China’s trajectory in context, it is useful to compare it with other innovation-intensive economies that have traditionally been the main recipients of royalty payments. Countries such as the U.S., Japan and Germany have long been at the technological frontier, not only producing cutting-edge innovations but also licensing them globally at scale. These economies serve as a benchmark for assessing China’s progress, both in terms of royalty levels and the extent to which domestic innovation is being commercialized abroad.

As shown in the next figure, China’s royalty receipts from the world have expanded rapidly in recent years, reflecting growing international demand for Chinese-owned intellectual property. While the level of royalties China receives remains well below that of established innovation leaders like the United States and Japan, and only recently surpassed Korea, it is the steepness of the curve that stands out. The trajectory underscores China’s growing role as a licensor of technology, even if it is not yet comparable in scale.

Royalties Received from Other Countries

SOURCES: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and authors’ calculations.

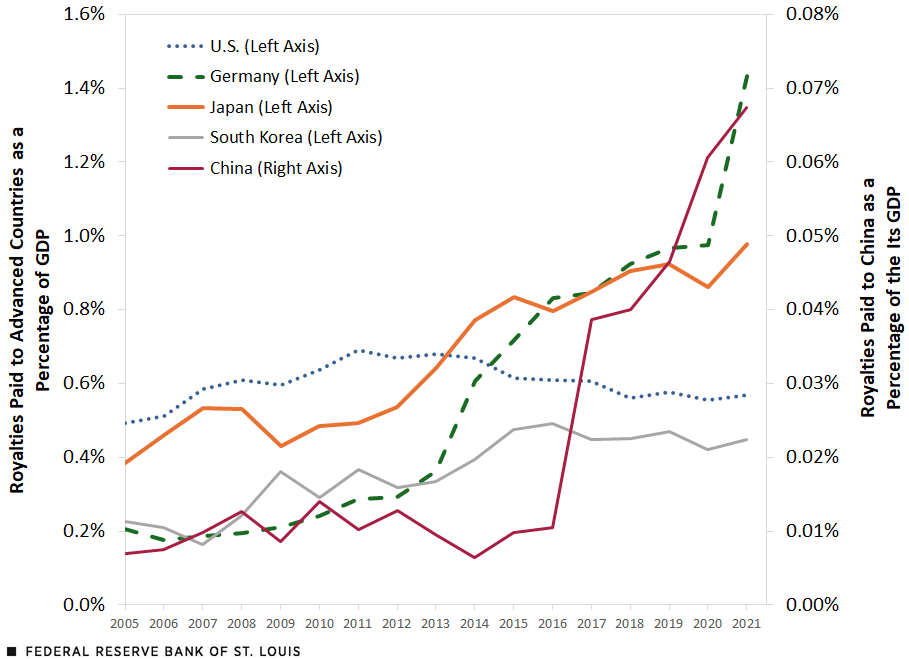

Yet absolute values alone do not fully capture China’s rise. When we scale royalty receipts by gross domestic product (GDP), a clearer picture emerges. The next figure plots royalties received as a share of GDP for China and four advanced economies. China’s royalty intensity still trails the top-tier countries: Royalties represented 0.07% of China’s GDP versus 0.45% of South Korea’s GDP. However, China’s growth rate is considerably faster than those of advanced countries in recent years. To make this trajectory more visible, China’s series is plotted on a separate (right-hand) axis. This helps highlight the acceleration in royalty-to-GDP terms, without compressing the variation across advanced economies. Even if China has not yet reached parity, it is catching up quickly, and the gap is narrowing.

Royalties Received from Other Countries as a Share of GDP

SOURCES: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and authors’ calculations.

Why It Matters

This evolution has important implications. For firms in advanced economies, competitive dynamics with China are no longer limited to cost advantages in manufacturing. Increasingly, Chinese firms are active in high-tech sectors where innovation, know-how, and intellectual property play a central role.

At the global level, this shift points to a more multipolar innovation landscape. While the U.S. and Europe have historically anchored global technological leadership, China’s growing presence suggests a diversification in the sources of innovation. This may ultimately enhance resilience and broaden the global base of knowledge production. At the same time, this shift introduces new complexities, both in terms of competition and in coordinating rules and standards across jurisdictions with different institutional frameworks.

Importantly, these changes are not inherently problematic. Innovation is not a zero-sum game: Knowledge is nonrival, meaning that its use by one person does not diminish its availability to others, and a broader technological frontier can yield widespread productivity gains. The rise of new innovation hubs, including China, has the potential to benefit the global economy as a whole. Still, as China transitions from being primarily a site of production to also a source of invention and licensing, the focus is no longer on whether it will catch up—but rather on how other countries and firms will adapt to its evolving role in global innovation networks.

Notes

- See Florencia Airaudo, François de Soyres, Alexandre Gaillard and Ana Maria Santacreu’s paper, “Recent Evolutions in the Global Trade System: From Integration to Strategic Realignment (PDF),” presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking 2025 in Sintra, Portugal; François de Soyres, Ece Fisgin, Alexandre Gaillard, Ana Maria Santacreu and Henry L. Young’s article “The Sectoral Evolution of China’s Trade,” FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Feb. 28, 2025; and François de Soyres, Ece Fisgin and Ana Maria Santacreu’s blog post, “Understanding China’s Technological Rise through Patent Data,” St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 3, 2025.

- See Jaedo Choi, George Cui, Younghun Shim and Yongseok Shin’s 2025 unpublished paper “The Dynamics of Technology Transfer: Multinational Investment in China and Rising Global Competition (PDF).”

- See Ana Maria Santacreu’s 2025 paper, “Dynamic Gains from Trade Agreements with Intellectual Property Provisions,” in the Journal of Political Economy.

Citation

François de Soyres, Ana Maria Santacreu and Ethan Hunt, ldquoChina’s Role in Global Innovation Is Changing,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 14, 2025.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions