Does Greater Economic Prosperity Bring Lower Mortality Rates?

Richer countries typically devote a growing share of national income to social services and health care. But does a nation’s greater income translate into longer life spans for its citizens?

In a recent Economic Synopses essay, Guillaume Vandenbroucke, an economist and assistant vice president at the St. Louis Fed, examined whether a country’s economic growth is the key driver behind gains in longevity.

Using annual data from the World Bank, Vandenbroucke analyzed real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and two measures of mortality, the crude death rate (CDR) and life expectancy at birth (LEB),The author defined the crude death rate to be the annual number of deaths per population. Life expectancy at birth is the expected life span of a newborn. for 86 nations.The author excluded China in these calculations because the country’s Great Leap Forward and then its one-child policy caused abnormal demographics.

Death Rates and Economic Growth

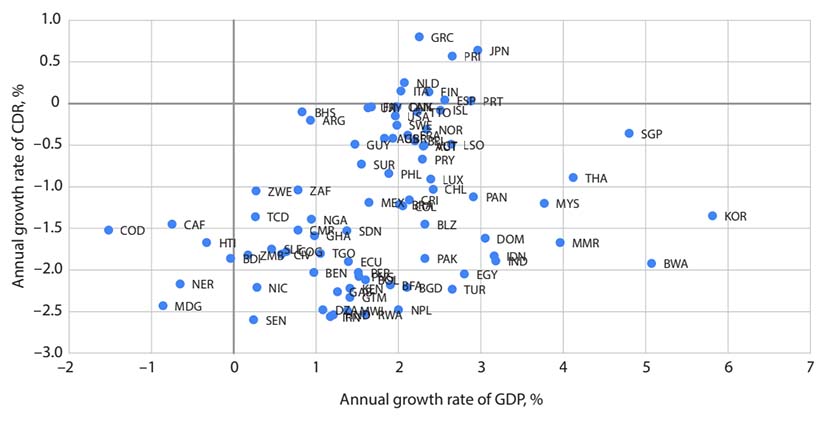

The figure below plots the relationship between a country’s crude death rate and its real GDP per capita between 1960 and 2019.

Economic Growth and Death Rates, 1960-2019

SOURCE: World Bank.

NOTE: CDR is crude death rate; GDP is real gross domestic product per capita.

As shown in the figure, the vast majority of countries experienced positive growth in real GDP per capita and a falling crude death rate during this period; these nations represented 86% of the world’s population in 1960.

Among his observations, the author pointed out that Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Puerto Rico and Spain were the only economies that experienced both increasing real GDP per capita and an increasing crude death rate; the seven countries and the U.S. territory represented 12% of the global population in 1960.

In a statistical analysis of the data, Vandenbroucke found that the correlation between growth of the crude death rate and real GDP per capita was 0.31.

“Thus, countries with higher economic growth had, on average, higher CDR growth; that is, their CDR tended to decrease slowly compared with countries with lower economic growth,” he wrote.

These findings appear to conflict with the idea that economic prosperity is a primary determinant of low mortality, the author noted, adding that the overall correlation between growth of the crude death rate and real GDP per capita should have been negative if that notion were true.

Vandenbroucke explained that this disconnect between economic growth and mortality may be due to the ability of poorer nations to implement cost-effective public health practices and education that reduce death, such as vaccinations.

A Look at Life Expectancy at Birth

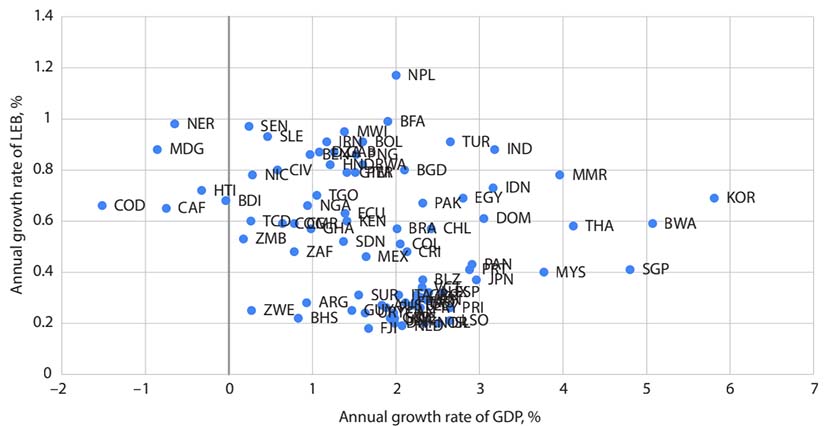

In a similar fashion, the author examined the relationship between life expectancy at birth and real GDP per capita, as shown in the figure below.

Economic Growth and Life Expectancy Rates, 1960-2019

SOURCE: World Bank.

NOTE: LEB is life expectancy at birth; GDP is real gross domestic product per capita.

The figure shows that life expectancy at birth improved for all countries, regardless of economic growth. This was true even for countries with a rising crude death rate; the author explained that this was possible because a country with an increasingly older population will experience a greater number of deaths per population.

In his statistical analysis, the author also found that countries with higher economic growth had, on average, lower growth rates for life expectancy at birth.

“In conclusion, the notion that mortality is determined largely by economic prosperity is not a good description of the world after 1960,” he wrote. “Reductions in mortality, measured by either decreasing CDR or increasing LEB, are not easily explained as resulting from economic growth.”

Notes

- The author defined the crude death rate to be the annual number of deaths per population. Life expectancy at birth is the expected life span of a newborn.

- The author excluded China in these calculations because the country’s Great Leap Forward and then its one-child policy caused abnormal demographics.

Citation

ldquoDoes Greater Economic Prosperity Bring Lower Mortality Rates?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 24, 2023.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions