The Economic Impact of Child Care by State

April 15, 2025

Child care is not just an issue for working parents; it also affects the wider economy. About 1 in 5 Americans ages 25 to 54 have a young child living with them. To work, they need access to child care, whether it’s formal—such as at a day care facility—or informal—such as with a family member.

However, high child care costs can be a financial burden on families and make it more challenging for parents and caregivers to contribute to the economy through the workforce. The data show that mothers of young children are less likely to participate in the labor force than other adults. Access to child care is particularly important for single parents, who are more likely to be women than men. While parents and caregivers may struggle with access and affordability, U.S. child care workers also earn significantly lower wages than the typical worker.

Child Care Data: Fact Sheets for All 50 States

Prepared by researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, these fact sheets include child care affordability estimates, data on single parenting and labor force participation rates (that is, the share of the civilian population working or looking for a job), and statistics about child care worker wages. Data are available for all 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

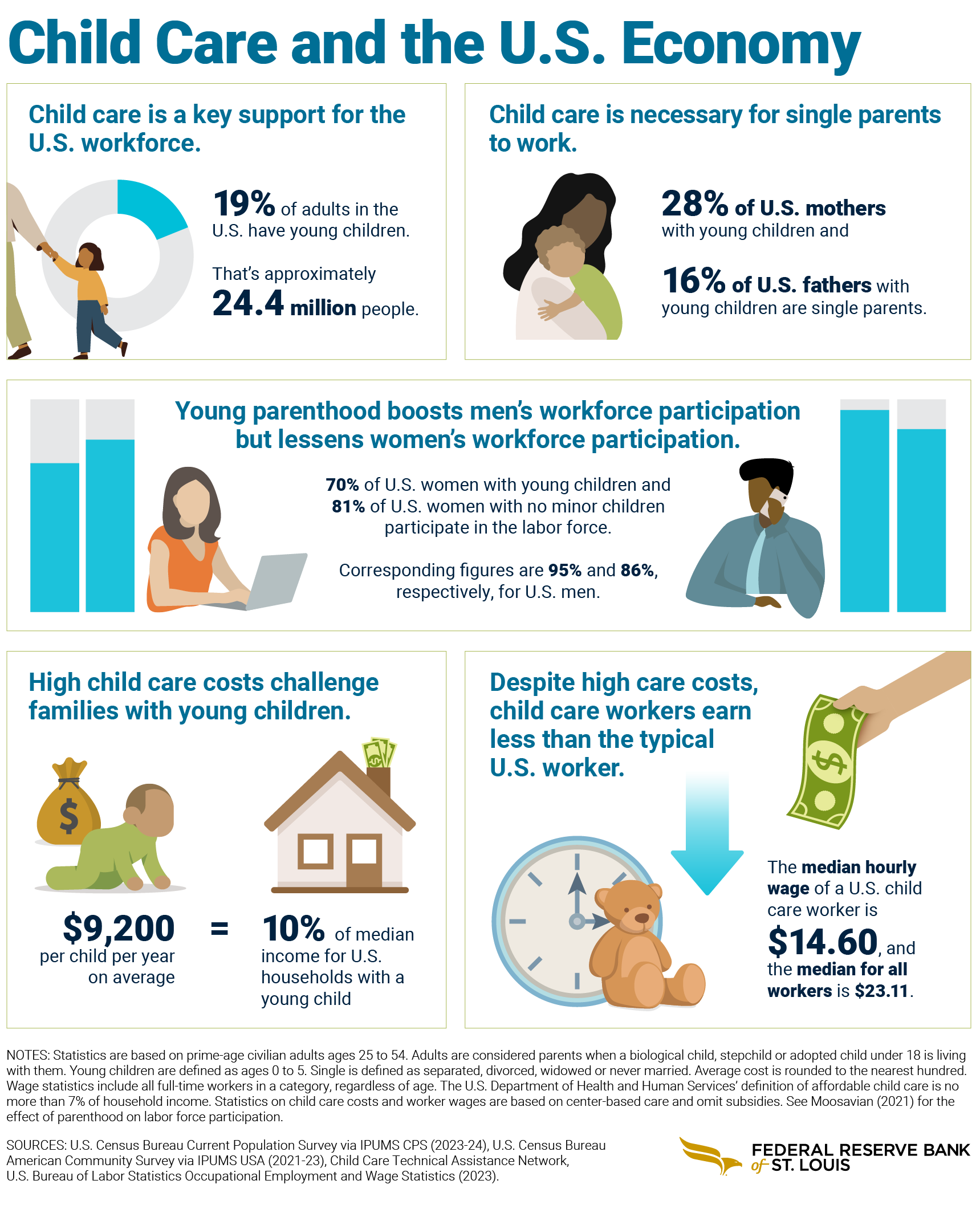

Snapshot: Child Care and the U.S. Economy

Below are some key U.S. child care and labor force statistics at a glance. Data are sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (via IPUMS CPS), U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (via IPUMS USA), Child Care Technical Assistance Network, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, and calculations by St. Louis Fed researchers.

Child care is a key workforce support.

- In 2024, 19% of adults in the U.S. had young children.

- That’s approximately 24.4 million people.

Child care is necessary for single parents to work.

- Between 2021 and 2023, 28% of U.S. mothers with young children and 16% of U.S. fathers with young children were single parents.

Young parenthood boosts men’s workforce participation but lessens women’s workforce participation.

- In 2024, 70% of U.S. women with young children and 81% of U.S. women with no minor children participated in the labor force.

- Corresponding figures were 95% and 86%, respectively, for U.S. men.

High child care costs challenge families with young children.

- In 2023, the average cost of child care in the U.S. was:

- $9,200 per child per year

- 10% of the median income for households with a young child

Despite high care costs, child care workers earn less than the typical worker.

- The median hourly wage of a U.S. child care worker was $14.60 in 2023.

- The median for all U.S. workers was $23.11.

Regional Economy: Child Care in the Eighth Federal Reserve District

The St. Louis Fed serves all of Arkansas and portions of six other states: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. Below are fact sheets for Eighth District states.

- View statistics for Arkansas (PDF)

- View statistics for Illinois (PDF)

- View statistics for Indiana (PDF)

- View statistics for Kentucky (PDF)

- View statistics for Mississippi (PDF)

- View statistics for Missouri (PDF)

- View statistics for Tennessee (PDF)

Related Resource

This information was prepared by Charles S. Gascon, Ana Hernández Kent and Jack Fuller using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (via IPUMS CPS), U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (via IPUMS USA), Child Care Technical Assistance Network, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, and their own calculations.

These fact sheets replace those published in 2021. In some cases, new information replaces previously available data. Statistics for the share of adults who are parents and the labor force participation rate use data from 2024. Statistics for the share of single parents combine data for 2021 through 2023. Statistics for child care costs and affordability use data from 2023. Statistics for wages use data from 2023.

- Statistics are based on prime-age civilian adults ages 25 to 54.

- Adults are considered parents if a biological child, stepchild or adopted child under age 18 is living with them.

- Young children are defined as those 5 years old and under.

- Single is defined as separated, divorced, widowed or never married.

- Average cost of child care is rounded to the nearest hundred.

- Statistics for wages include all full-time workers in a category, regardless of age.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ definition of affordable child care is no more than 7% of household income.

- Statistics on child care costs and worker wages are based on center-based care and omit subsidies.

- See Zeytoon Nejad Moosavian’s 2021 Journal of Economics and Political Economy article, “Identifying the Effect of Parenthood on Labor Force Participation: A Gender Comparison,” for the effect of parenthood on labor force participation.

Please contact mediainquiries@stls.frb.org.