How COVID-19 May Be Affecting Inflation

COVID-19 dramatically altered the spending patterns of U.S. consumers, as people avoided restaurants, bars and movie theaters. Has the pandemic also upturned the measurement of inflation?

Most years, measuring inflation is a pretty dull affair. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses surveys to gather data on the prices of goods and services purchased across the U.S., weights these prices by how much they contribute to the typical basket of expenditures, and then aggregates to form the consumer price index (CPI). Inflation is then measured as the rate of growth of the CPI over a specific period.

Weighting of Expenditures

While not immediately obvious, the chosen weights are crucial to appropriately measuring the price pressures faced by the typical consumer. Due to their importance, these weights are reevaluated each year as consumer purchasing patterns change over time.

As an example, consider the “Food at Home” category, which is an aggregate bundle of food and nonalcoholic beverages purchased at grocery stores and consumed at home. This category is given a weight that declined modestly from 9.6% to 7.6% over the last twenty years. In particular, a weight of 7.6% for Food at Home was used to construct the official CPI-based inflation across all of 2020.The weights used to construct the official CPI-based inflation for 2020 were determined in December 2019, and these weights were based on consumer spending habits in 2017-18. Expenditure data for 2019 would have been considered preliminary and hence were not used in the construction of the weights.

The problem is that 2020 was not your typical year. Consumer spending patterns changed dramatically because of COVID-driven stay-at-home orders and behavioral changes associated with social distancing. This implies that the “true” weights in 2020 were probably unlike the official weights that the BLS constructed based on the consumption habits of consumers in the 2017-18 period. While this is intuitively true, constructing weights for 2020, using data from 2020, is not a trivial exercise.

Adjusting for the Pandemic

Nevertheless, Alberto Cavallo, an economics professor at Harvard Business School, constructed expenditure weights for each month of 2020 using data from the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker at Harvard University and Brown University as compiled by Raj Chetty and other economists.

Cavallo’s weights are, no doubt, imprecise but seem reasonable. For example, we know that consumer expenditures at restaurants fell sharply in 2020. It therefore seems likely that expenditures on Food at Home (Food Away from Home) likely increased (decreased) in 2020 and hence the true expenditure weights should be higher (lower) than normal for these categories. In fact, these weights are estimated to have increased (decreased) by 3.76 (3.07) percentage points during the month of April 2020, when stay-at-home orders were most severe for much of the country.

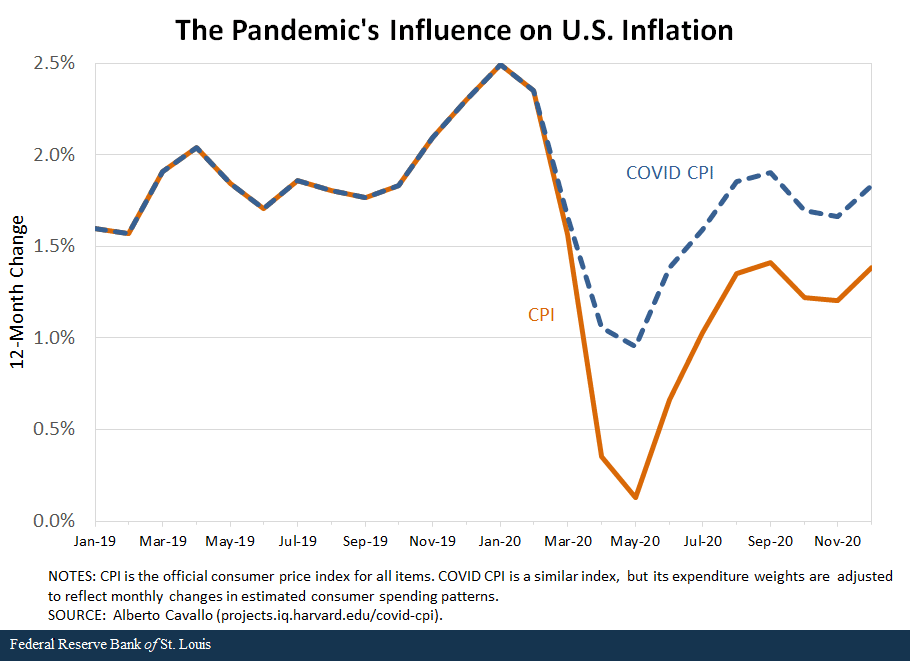

Having the estimated expenditure weights for 2020, we can then compare the official CPI-based inflation with an unofficial COVID CPI-based inflation that is easily accessible at Cavallo’s website. Below we replicated his figure “U.S. COVID inflation (all-items, 12-month change).” There are two lines. The solid orange line represents year-over-year CPI-based inflation while the blue dashed line represents the same, but for the COVID CPI measure.

It is immediately clear that there is a substantial difference between the two lines. COVID CPI-based inflation is typically about 50 basis points higher than that associated with the official measure produced by the BLS.

In the context of our Food at Home example, this makes sense. Across much of the year, food shortages at grocery stores led to higher prices as those retailers competed for access to goods from disrupted supply chains. Similarly, the lack of demand for inside dining at restaurants led to lower prices at these restaurants as they struggled to entice customers to purchase their products.

Together, the combination of higher (lower) than normal expenditures of and higher (lower) than normal prices of Food at Home (Food Away from Home) would imply a higher COVID CPI-based inflation rate than the official one reported by the BLS.

Long-run Impact of the Gap

Moving forward, the gap between the two CPI measures introduces problems for the BLS. In subsequent years, will they treat 2020 as an anomaly or use data from 2020 to estimate expenditure weights? The answer likely depends on whether consumer behavior has changed permanently.

An example of where it might be a permanent change is associated with individuals who can work from home. If many consumers continue to work from home, spending on transportation may remain lower than it was pre-pandemic as the number of people commuting remains diminished. Similarly, the demand for housing may increase in the long run as these individuals rent and purchase larger units that have extra space for home offices.

The BLS’s methodology to deal with these changes could have many large implications for the economy. For example, workers and recipients of government assistance programs (e.g., Social Security) often receive adjustments to their wages and benefits based on the CPI.

Notes and References

- The weights used to construct the official CPI-based inflation for 2020 were determined in December 2019, and these weights were based on consumer spending habits in 2017-18. Expenditure data for 2019 would have been considered preliminary and hence were not used in the construction of the weights.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: COVID-19: Forecasting with Slow and Fast Data

- On the Economy: The St. Louis Fed's Financial Stress Index, Version 2.0

- On the Economy: Why the Same Inflation Target May Not Fit All Countries

Citation

Michael W. McCracken and Aaron Amburgey, ldquoHow COVID-19 May Be Affecting Inflation,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Feb. 2, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions