Trade and Gold Reserves after the Demise of the Classical Gold Standard

The following post is the second in a two-part series that examines the changing relationship between trade and U.S. gold reserves throughout history. The first post looked at the period from around 1870 to the start of World War I.

There have been significant changes to U.S. gold holdings over time. Were the changes linked to trade flows?

In a Regional Economist article, Assistant Vice President and Economist Yi Wen and then-Research Associate Brian Reinbold explored the relationship between trade and America’s gold reserves throughout the country’s history.

They explained that, under a gold standard, one would expect the U.S. to accumulate gold when it runs trade surpluses and for gold to flow out when the U.S. runs trade deficits.

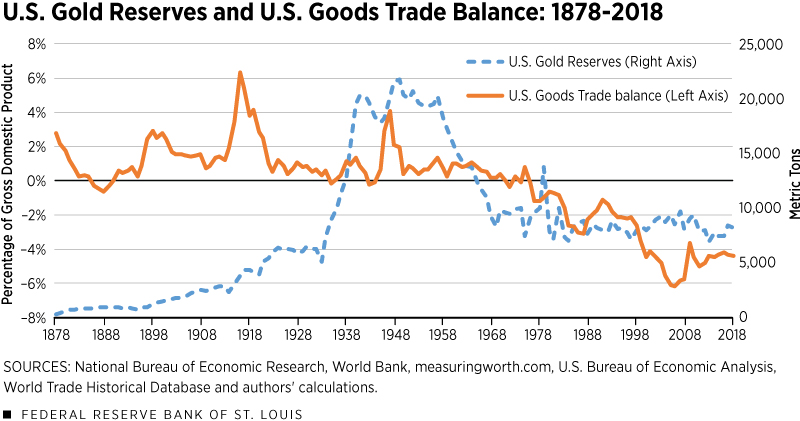

“In general, we see the U.S. accumulating gold as it ran trade surpluses from 1878 until the early 1920s, but afterward this relationship was tenuous at best as the international payments system experienced heightened uncertainty and significant change,” the authors wrote.

Trying to Save the Gold Standard

From around 1870 to the outbreak of World War I, the classical gold standard ensured that changes in a nation’s gold reserves were closely linked to changes in its trade balance, Wen and Reinbold wrote.

When World War I began, European countries suspended convertibility to gold to make financing the war effort easier. The war left the international payments system in ruins and the gold standard struggling. In addition, the costs of the war led to huge trade imbalances that, in turn, led to large fluctuations in countries’ gold reserves, the authors explained.

To return to the gold standard after the war, Great Britain needed to lower the price level, wait for sterling appreciation and attract gold reserves to return to the old parity, the authors wrote. In order to accomplish this, Great Britain raised its Bank rate to as high as 7% by 1920 at the expense of the domestic economy. This led to an economic depression due to shrinking credit.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve Banks raised the discount rate to as high as 7% by 1920. This was in an effort to fight inflationary pressures and defend the gold standard, which led to an economic depression, the authors noted.

This competition between the U.K. and the U.S. to attract gold by raising rates made it more difficult to realign world gold reserves and exchange rates, Wen and Reinbold wrote.

While most of the developed world had returned to the gold standard by the mid-1920s, systemic imbalances still existed, the authors pointed out.

The Shift from Gold

Unprecedented international deflation during the Great Depression destroyed any remnants of the classical gold standard, Wen and Reinbold wrote. Great Britain abandoned the gold standard in 1931.

The U.S. suspended gold convertibility and gold exports in 1933. The following year, the U.S. dollar was devalued and gold began to flow into the country, quadrupling its gold reserves within eight years. By 1950, the U.S. controlled nearly two-thirds of the world’s gold reserves, up from about 40% in 1930. The large U.S. gold stockpile created a world imbalance and prevented other nations from returning to the gold standard under the old parities, the authors noted.

The Bretton Woods System

The Bretton Woods system was created after World War II. Under this system, the U.S. dollar was tied to gold and other currencies were tied to the value of the U.S. dollar, the authors explained. This created a system of fixed exchange rates.

Yet, the relationship between gold and trade that was seen before World War I did not return.

“Although gold indirectly backed the international payments system during Bretton Woods, the mechanism to balance trade flows through the exchange of gold did not function as we saw under the classical gold standard,” Wen and Reinbold wrote.

They pointed out that from 1957 to 1970, the U.S. ran slight trade surpluses, yet the country saw a large outflow of gold. U.S. gold reserves were halved by 1970, as shown by the figure below.

Eventually, fear that the U.S. couldn’t meet its gold-dollar exchange rate ended this system in the 1970s, giving rise to the current system of fiat currencies and floating exchange rates, Wen and Reinbold explained.

U.S. gold reserves have remained relatively stable despite increasing U.S. trade deficits since the end of Bretton Woods, which, the authors concluded, underscores the present weak (and possibly nonexistent) link between gold and trade flows.

Citation

ldquoTrade and Gold Reserves after the Demise of the Classical Gold Standard,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 1, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions