Trade and U.S. Gold Reserves during the Classical Gold Standard Era

The following post is the first in a two-part series that examines the changing relationship between trade and U.S. gold reserves throughout history. The second post looks at trade and gold reserves after the demise of the classical gold standard.

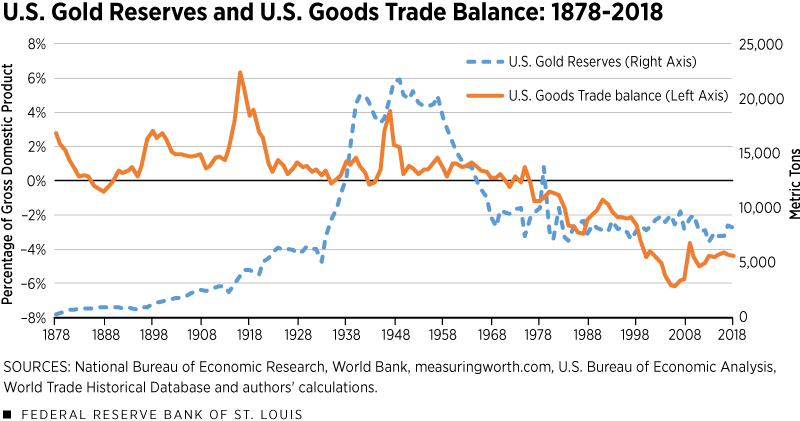

The dollar was tied to the value of gold throughout most of U.S. history, and the U.S. experienced significant changes to its gold holdings over time. But how did U.S. trade patterns affect America’s gold reserves before World War I?

In a Regional Economist article, Assistant Vice President and Economist Yi Wen and then-Research Associate Brian Reinbold explored the relationship between trade and America’s gold reserves during different time periods throughout history. This post focuses on the classical gold standard era, during which changes in a nation’s gold reserves were closely linked to changes in its trade balances.

The Gold Standard Flourishes

From around 1870 to the start of World War I—the period referred to as the classical gold standard—the value of gold formed the basis of the international monetary system. During this time a nation’s currency could be exchanged at any time for a fixed quantity of gold, the authors explained.

This led to a system of fixed exchange rates, they added, and balance of payments between nations were adjusted by gold flows to maintain the rates. Wen and Reinbold provided the example that if a nation runs a trade surplus under this system, that nation will then have a net inflow of gold; conversely, a trade deficit leads to a net outflow of gold. Therefore, it becomes difficult for a country to sustain persistent trade deficits because that leads to persistent net outflows of gold, in turn making it difficult to defend the gold parity.

“Ultimately, adhering to the gold standard prevents large gyrations in a nation’s balance of payments,” Wen and Reinbold wrote. “In addition, fixed exchange rates make the cost of foreign goods more predictable, which can facilitate international trade.”

Overall, the authors determined, the gold standard functioned well during this period, and the industrialized world experienced unprecedented peace, economic growth and stability, and trade openness.

World War I Brings Struggles

During World War I and its aftermath, the gold standard struggled. When World War I started, European countries suspended convertibility to gold so that they could more easily finance the war effort. Nations resorted to inflationary financing of their debt, the authors wrote, which could not easily be done when constrained by gold.

After the war ended, the international payments system was left in ruins, they noted.

“Especially for Europe, returning to the gold standard presented a formidable task after four years of inflation, price controls and exchange controls,” Wen and Reinbold wrote. “It would require deflation to return to the prewar price level under the old parity.”

The authors noted that the costs of the war led to huge trade imbalances that then led to large fluctuations in countries’ gold reserves. A return to the gold standard under the old parity would have required international adjustments in nations’ gold reserves, as the U.S. ran large trade surpluses and accumulated gold reserves during World War I and many European countries ran trade deficits and saw their gold reserves decline.

Citation

ldquoTrade and U.S. Gold Reserves during the Classical Gold Standard Era,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 31, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions