COVID-19: What Do FREDcast Users Think about Economic Growth?

Questions abound about the economic effects of the COVID-19 outbreak. For example, what will its effect be on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP)? While expert opinions are both interesting and valuable, we ask a different question: What does the general public think about the economic effects of the coronavirus outbreak?

FREDcast Data

To answer this question, we used FREDcast forecasts. FREDcast is an online forecasting game in which participants compete through their forecasts of four macroeconomic indicators:

- GDP growth

- Inflation

- Payroll employment growth

- Unemployment rate

While available for free to the general public, FREDcast is primarily used by students and teachers as a real-world application of economic content: Students learn the data (and, consequently, the economic theory) through repeated exposure via monthly forecasts. Real-time events—such as the COVID-19 outbreak—can be integrated into the instructors' lessons to demonstrate how they can affect economic data.

FREDcast forecasts are due on the 20th of each month. During the first three months of the year, participants forecast first-quarter GDP growth. Thus, through Feb. 20—before the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S.—FREDcast participants forecasted first-quarter GDP twice: once in January and once in February.

By March 20, participants also forecasted first-quarter GDP growth; however, during this period, they became aware of the spread of the coronavirus and had the opportunity to update their beliefs about first-quarter GDP.While news of the virus circulated before the Feb. 20 deadline, the decline in the stock market began in earnest after the February deadline.

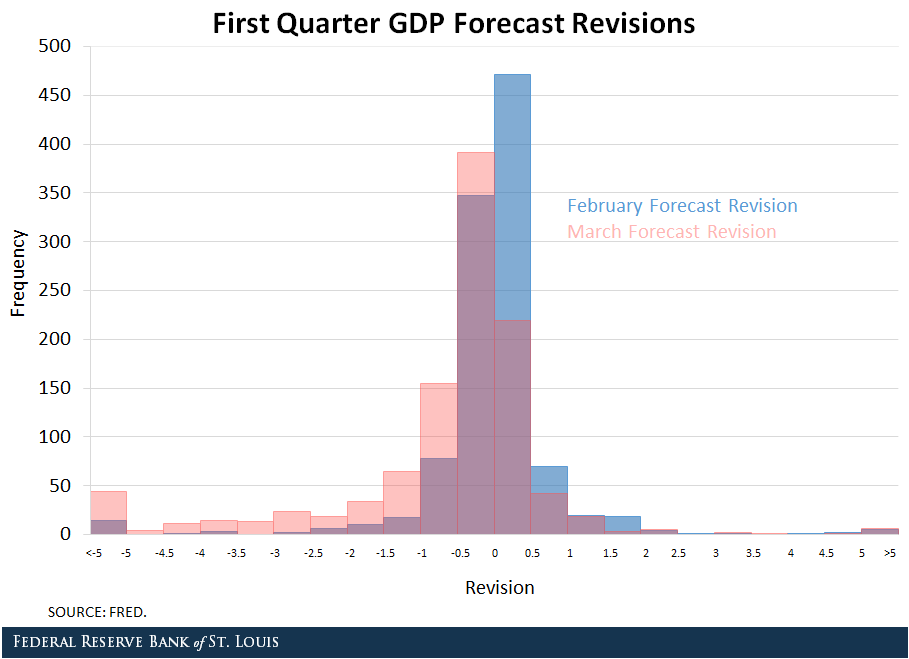

The figure below shows changes in first-quarter GDP growth forecasts between months:

- The blue histogram displays the distribution of percentage-point changes in individuals' first-quarter GDP growth forecasts from January to February.

- The red histogram displays the distribution of the changes in the same individuals’ forecasts from February to March, after the virus began to spread in the U.S.

We can treat the changes from January to February as a baseline forecast revision, or how people change their outlooks as the horizon shrinks and news comes in.

What FREDcast Users Think

FREDcast users became a bit more pessimistic about U.S. GDP growth in February: Their average forecast revision from January to February was -0.2 percentage points, and their median revision was 0 percentage points.

However, just after Feb. 20, the stock market fell on the announcement of a dramatic increase in COVID-19 cases outside of China, and it continued to decline through March. Additionally, over the March forecast period, health care professionals and state governments issued social distancing and “stay-at-home” recommendations, curbing consumer spending in many industries.

In light of these developments, users had the opportunity to revise their opinions about the future of the economy. The average revision between February and March was -1 percentage points—meaning that users, on average, marked their forecasts down a full 100 basis points—and the median revision was -0.3 percentage points.

Moreover, 44 users marked their first-quarter GDP growth forecast down 500 basis points or more. These results suggest the responsiveness of the general public’s view of the economy to major news events. Some economic surveys (such as the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers) endeavor to generate a representative distribution of households. While FREDcast users are generally not professional forecasters, they typically are taking or have taken some economics classes and should not be considered a representative sample of households (and should not be thought of as reflecting any opinion of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).

FREDcast Users Versus Professional Forecasters

FREDcast users’ forecast revisions generally follow the same trend as those of professional forecasters. In late February, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase forecasted 1.2% and 1.5% first-quarter GDP growth, respectively. As of March 24, those forecasts had fallen to -6% and -4%.See the Goldman Sachs forecast in February versus in March and the JP Morgan Chase forecast in February versus in March.

With so much uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak, it is difficult to determine exactly what its effect will be on GDP growth, and forecasters are updating their projections frequently to account for the most up-to-date news. Over the course of the pandemic and in the months following, it will be interesting to keep a pulse on how both professionals as well as the general public expect the U.S. economy to change.

Notes and References

1 While news of the virus circulated before the Feb. 20 deadline, the decline in the stock market began in earnest after the February deadline.

2 Some economic surveys (such as the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers) endeavor to generate a representative distribution of households. While FREDcast users are generally not professional forecasters, they typically are taking or have taken some economics classes and should not be considered a representative sample of households (and should not be thought of as reflecting any opinion of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).

3 See the Goldman Sachs forecast in February versus in March and the JP Morgan Chase forecast in February versus in March.

Additional Resources

Citation

Michael T. Owyang, Julie Bennett and Hannah Shell, ldquoCOVID-19: What Do FREDcast Users Think about Economic Growth?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, March 29, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions