The Impact of the Fed’s Response to COVID-19 So Far

As part of the measures undertaken to alleviate the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve lowered its policy rate back to zero and opened a series of credit facilities designed to support the functioning of financial markets.See Martin, Fernando M. “Economic Realities and Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Part I: Financial Markets and Monetary Policy,” Economic Synopses, 2020, No. 10; and Neely, Christopher J. “Central Bank Responses to COVID-19,” Economic Synopses, 2020, No. 23. In addition, the Fed announced actions aimed at relieving cash-flow stress for small and medium-sized businesses, as well as municipalities.For example, see the Federal Reserve announcements on April 9, April 27, April 30 and June 8. Here, I use the Fed's balance sheet to help illustrate what has been done so far.

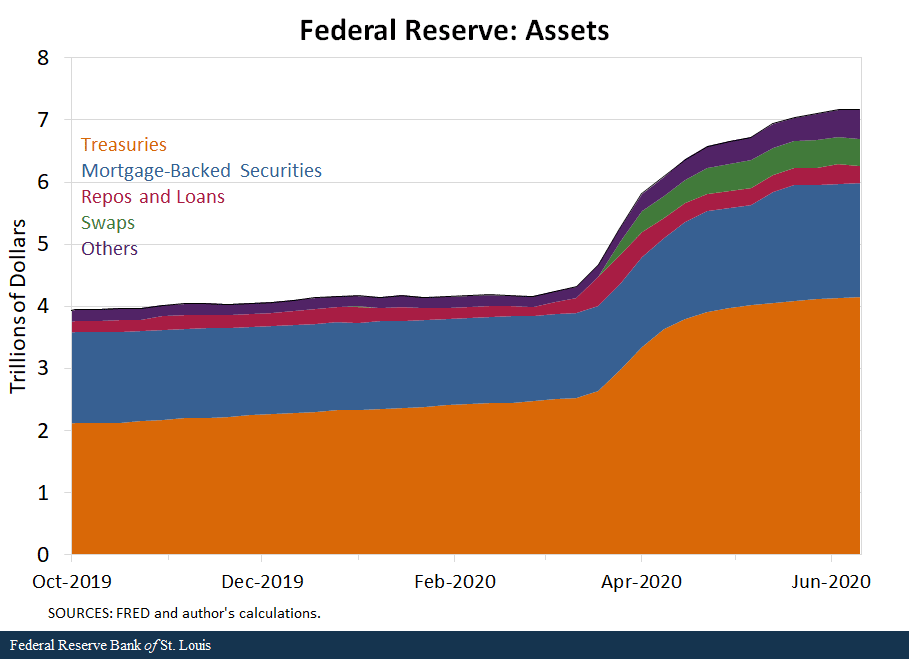

The figure below shows a decomposition of the assets of the Federal Reserve. These data are published weekly by the Fed. As of June 10, the latest data available, total assets were about $7.2 trillion. Since the end of February, assets have grown $3.0 trillion, a 72% increase.

The majority of this increase, about $1.7 trillion, was due to purchases of Treasury securities, mostly notes and bonds (i.e., with a maturity longer than a year). Two other important, though much smaller, contributors to asset growth were purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and liquidity swaps with other central banks, roughly $450 billion each. The remaining components contributed a combined $400 billion; notably, given the opening of several credit facilities as described above, repurchase agreements (repos) and loans have so far increased only slightly, roughly $100 billion.

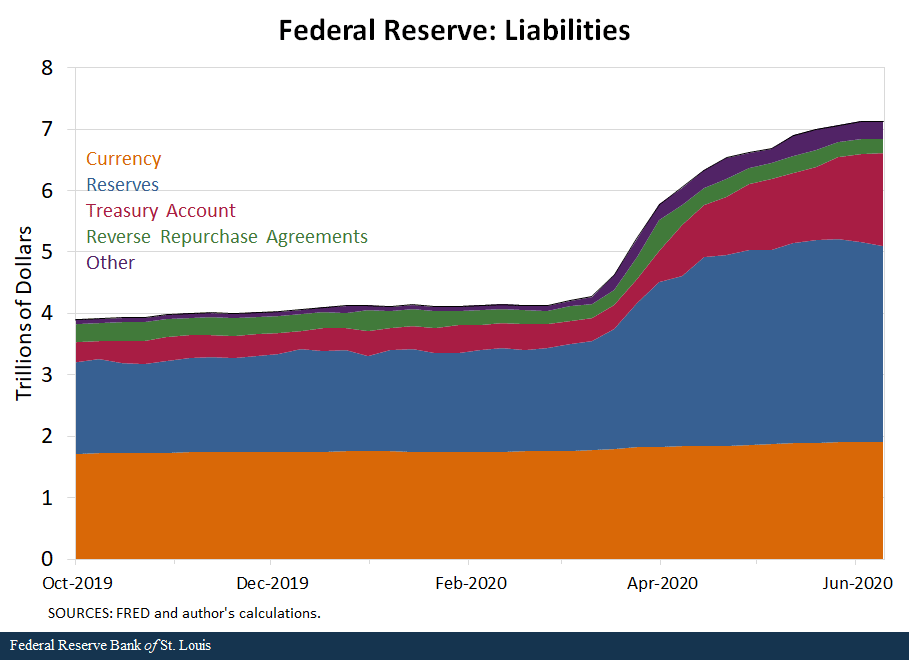

An increase in assets implies a corresponding increase in liabilities. The next figure shows a decomposition of the liabilities of the Federal Reserve.

Not surprisingly, the purchase of Treasury securities was roughly met by an increase in the reserves of depository institutions, about $1.5 trillion since the end of February. Bank reserves peaked in late May at $3.3 trillion, the highest they have ever been, and are now slightly lower, at about $3.2 trillion. In contrast, currency in circulation has grown only $150 billion.

Another big contributor to liabilities growth was the general account of the U.S. Treasury, which increased by $1.1 trillion. This component will eventually contract and convert into currency and reserves, as the Treasury spends the proceeds from its recent debt issuance. The use of reverse repurchase agreements saw an initial surge, rising from roughly $200 billion at the end of February to $500 billion at the beginning of April, but has since declined and returned to pre-pandemic levels.Most of the surge in early April is due to the use of the Overnight Repurchase Agreement Facility. This facility allows primary dealers and an expanded set of counterparties—such as banks, money market funds and government sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—to lend liquidity to the Fed. More information on this facility is available at the Federal Reserve and the New York Fed.

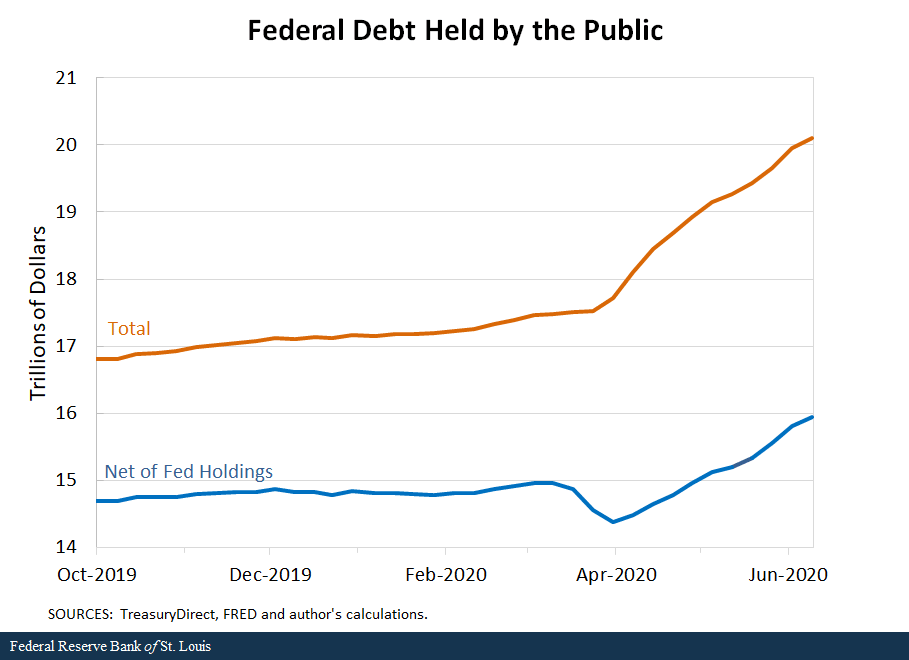

While the Fed has been buying government debt, the Treasury has been running large deficits and thus issuing more debt. The figure below shows the net effect. During the current fiscal year, which started on Oct. 1, 2019, federal debt in the hands of the public has increased about $3.3 trillion. The definition of the public includes the Federal Reserve.

If we net out these holdings, there has been a much smaller increase in the government debt held by the non-Fed public, about $1.25 trillion. So far this fiscal year, the Federal Reserve has purchased over $2 trillion in Treasury debt, $1.7 trillion since the end of February, as described above. Put differently, the Federal Reserve has bought 62% of the debt issued by the Treasury to the public during the current fiscal year.

Fed intervention thus far has mostly consisted of absorbing longer-term Treasury debt from markets. These purchases implied a corresponding increase in bank reserves. In effect, the Fed has transformed Treasury liabilities into central bank liabilities.

According to the latest estimates by the Congressional Budget Office, the federal budget deficit in fiscal year 2020 would reach $3.7 trillion.See the CBO’s monthly budget review for April. This would roughly equal an additional $400 billion in public debt during the remainder of the current fiscal year. It remains to be seen whether this new debt will end up being held by the private sector or being transformed into bank reserves.

Notes and References

1 See Martin, Fernando M. “Economic Realities and Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Part I: Financial Markets and Monetary Policy,” Economic Synopses, 2020, No. 10; and Neely, Christopher J. “Central Bank Responses to COVID-19,” Economic Synopses, 2020, No. 23.

2 For example, see the Federal Reserve announcements on April 9, April 27, April 30 and June 8.

3 Most of the surge in early April is due to the use of the Overnight Repurchase Agreement Facility. This facility allows primary dealers and an expanded set of counterparties—such as banks, money market funds and government sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—to lend liquidity to the Fed. More information on this facility is available at the Federal Reserve and the New York Fed.

4 See the CBO’s monthly budget review for April.

Additional Resources

Citation

Fernando M. Martin, ldquoThe Impact of the Fed’s Response to COVID-19 So Far,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, June 16, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions