Monetary Policy’s Potential Effects on the Deficit, Debt and Fiscal Policy

Over the next decade, the federal government is expected to continue running substantial deficits, resulting in further debt accumulation. According to the latest projections by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the primary deficit will average 2.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) from 2020 to 2029.All years in this post are fiscal years. The U.S. fiscal year begins on October 1, ends on September 30 of the subsequent year and is designated by the year in which it ends. Before 1977, the fiscal year began on July 1 and ended on June 30. CBO projections are as of August 2019.

Though this figure is lower than the average primary deficit sustained since the financial crisis (2008-2019)—about 3.7% of GDP—it is still much higher than in the preceding postwar period (1955-2007), when the average primary deficit was roughly zero.

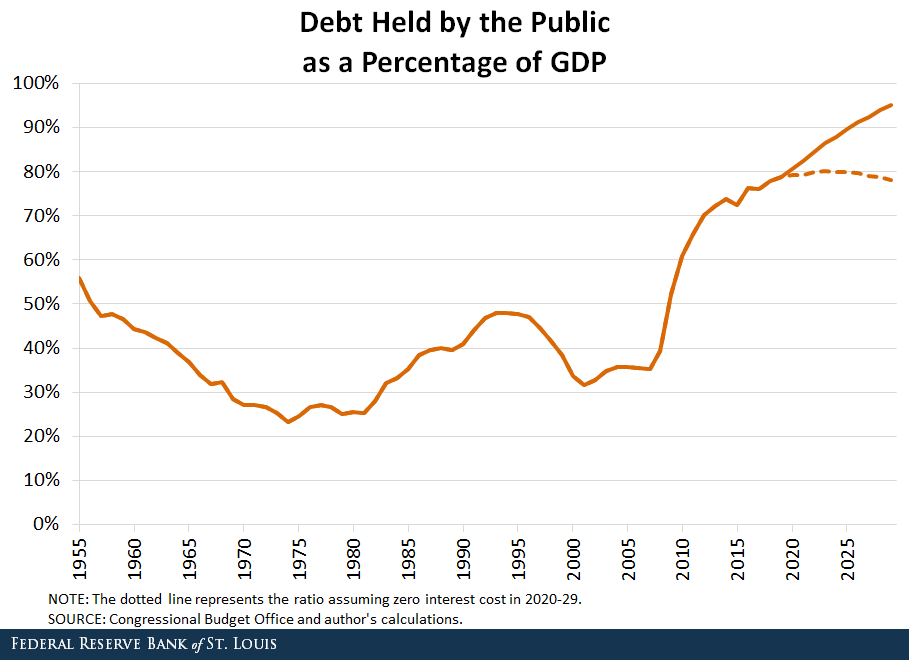

The natural consequence of these mounting deficits is a substantial accumulation of government liabilities. Debt held by the public was 35% of GDP in 2007, climbed to 79% of GDP by 2019 and is projected to reach 95% of GDP by 2029.“Debt held by the public” excludes holdings by federal agencies (such as Social Security trust funds) but includes holdings by Fed banks.

Monetary Policy, Debt and the Deficit

While monetary policy as conducted by the Fed does not aim at directly assisting the Treasury Department’s financial needs, it nevertheless has a non-trivial impact on the deficit and debt:

- First, the Fed’s interest rate policy affects the cost of servicing the public debt.

- Second, the Fed’s balance sheet includes substantial holdings of U.S. Treasury securities, providing relief to the financing the Treasury needs to procure from the private sector.

- Third, the Fed remits its profits to the Treasury, which count as additional revenue for the government.

The CBO’s projections make assumptions on the future path of monetary policy. Specifically, it needs to assume a certain path for interest rates to project the service cost of debt.

The most recent projections expect the annual federal funds rate to steadily climb from 2.3% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2029. Correspondingly, the interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond is expected to increase from 2.3% to 3.2%. And while the CBO projects Fed profit remittances to the Treasury, it does not provide estimates on how much debt held by the public will be absorbed by Fed banks.

Possible Effects of Lowering Interest Rates

At its July meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target range for the federal funds rate, reversing the trend of raising rates since December 2015. It again lowered the target range at its September and October meetings.

Given this policy reversal and the domestic and global downward pressure on government bond yields, one could argue that current CBO projections overestimate the future cost of servicing the public debt. Estimating the likely path of interest rates over the next decade is of course a difficult task. Instead, I will provide a sense of the potential impact that interest rate policy can have on the federal debt.

Consider the extreme scenario that the federal government is able to issue all its debt at an interest rate of zero.This scenario is not as unlikely as it sounds: Currently, yields on 10-year German and Swiss bonds are negative. Consistent with this scenario, I will assume Fed remittances drop to zero as well, though the impact of this assumption is relatively minor.

The figure below shows debt held by the public as a fraction of GDP, as estimated by the CBO and assuming no interest cost (and zero Fed remittances) from 2020 onwards.

Two main lessons arise. First, the impact of interest costs on debt accumulation is significant: By 2029, the added debt due to service costs amounts to about 17% of GDP, a figure similar to the yearly outlays of the federal government.

Second, even if the government were able to issue all its debt at zero cost, the size of the debt would remain significant at about 78% of GDP by 2029. The impact of assuming zero Fed remittances is 2% of GDP. That is, the debt-to-GDP ratio would climb to 76% of GDP by 2029 if they were to remain at current projected levels instead of going to zero.

Balance Sheet Implications

Projecting the impact of the Fed’s balance sheet policy is even trickier. The FOMC recently reaffirmed its intentions to operate in an “ample reserves” regime for the effective conduct of monetary policy. But ample reserves are hard to quantify. Again, we can run scenarios to gauge the potential impact.

For example, one could expect the balance sheet of the Fed to grow with the demand for currency. Currency in circulation has recently been growing around 6% annually, mostly driven by foreign demand for high-denomination bills.Martin, Fernando. “Foreign Demand for Currency and the Fed’s Balance Sheet,” St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 7, 2019.

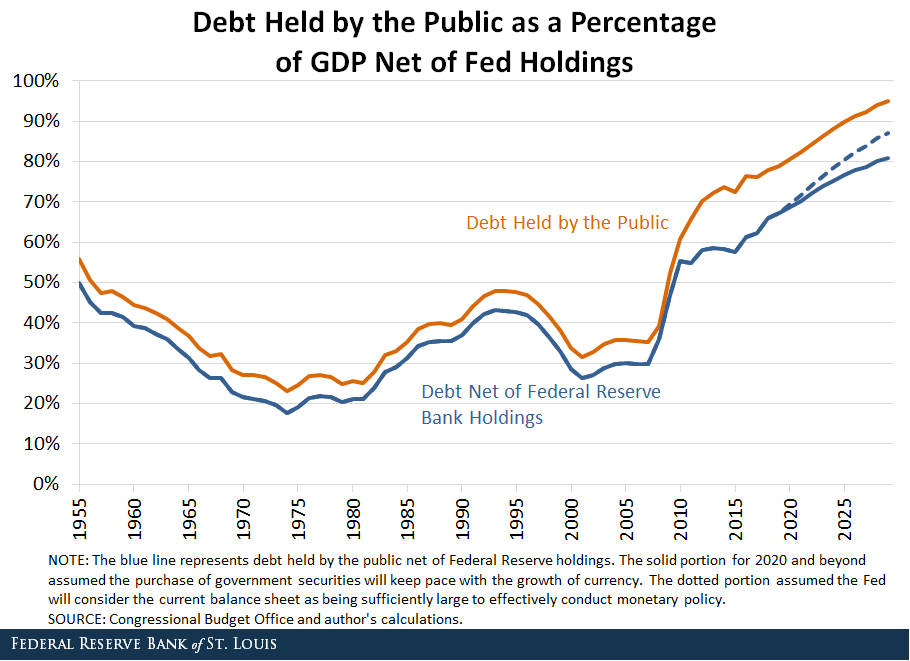

One could assume that the purchase of government securities will keep pace with the growth of currency. On the other extreme, one could also assume that the Fed will consider the current balance sheet as being sufficiently large to effectively conduct policy. The impact of these two disparate scenarios is illustrated in the figure below.The most recent projections for the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio estimate the evolution of Fed liabilities between now and 2025. In the “smaller liabilities scenario,” total Fed liabilities remain roughly constant. Under the “larger liabilities scenario,” total Fed liabilities grow at about 3.8% per year. The assumed annual growth rate for currency is 3% and 6% for each case, respectively.

The difference between the two scenarios described above would account for about 6% of GDP in terms of accumulated debt by 2029. Under the first scenario described, debt in the hands of the public—net of Fed holdings—would climb from 67% of GDP in 2019 to 81% of GDP in 2029. Under the second scenario, debt would increase to 87% of GDP by 2029.

One could further finesse these estimates by evaluating the impact on Fed remittances, but the bottom line remains the same: These are significant numbers, affecting how much financing the federal government would need to procure from the private sector, domestic and abroad.

The Fed is tasked with achieving low and stable inflation, promoting maximum employment and maintaining a stable financial system. The policies implemented to achieve these goals have an impact on the federal government’s deficit and debt. These effects are potentially large and, in turn, affect the future conduct of fiscal policy.

Notes and References

1 All years in this post are fiscal years. The U.S. fiscal year begins on October 1, ends on September 30 of the subsequent year and is designated by the year in which it ends. Before 1977, the fiscal year began on July 1 and ended on June 30. CBO projections are as of August 2019.

2 “Debt held by the public” excludes holdings by federal agencies (such as Social Security trust funds) but includes holdings by Fed banks.

3 This scenario is not as unlikely as it sounds: Currently, yields on 10-year German and Swiss bonds are negative.

4 Martin, Fernando. “Foreign Demand for Currency and the Fed’s Balance Sheet,” St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 7, 2019.

5 The most recent projections for the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio estimate the evolution of Fed liabilities between now and 2025. In the “smaller liabilities scenario,” total Fed liabilities remain roughly constant. Under the “larger liabilities scenario,” total Fed liabilities grow at about 3.8% per year. The assumed annual growth rate for currency is 3% and 6% for each case, respectively.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Safe Assets in the U.S. Economy

- On the Economy: Did Bond Purchases and Forward Guidance Affect Bond Yields?

- On the Economy: Is the Fed’s Taper Making the National Debt Situation Look Worse?

Citation

Fernando M. Martin, ldquoMonetary Policy’s Potential Effects on the Deficit, Debt and Fiscal Policy,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 14, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions