Fed Payments to Treasury and Rising Interest Rates

The Federal Reserve increased the federal funds rate target seven times since between Dec. 2015 and June 2018. This has implications for the path of the federal deficit and federal debt in two ways:

- Directly through net interest payments

- Indirectly through the yearly remittances from the Fed to the U.S. Treasury Department

The yearly remittances to the Treasury are essentially the leftover Fed revenue after operating expenses. By law, this additional revenue must be turned over to the Treasury.

The revenue sent to the Treasury peaked at $97.7 billion in 2015 and has been steadily falling since. In January, the Fed sent $80.2 billion to the Treasury. In this blog post, I explore why these transfers are likely to continue declining.

Interest Rates and Treasury Payments

The federal deficit is the sum of the primary deficit and net interest payments:

- The primary deficit is the difference between government expenditures (excluding interest payments) and government revenues (excluding interest receipts).

- Net interest payments correspond to total interest paid on government debt to the public (minus interest earned) and depend directly on the path for short- and long-term interest rates. The effects of the gradual increase in the federal funds rate target on government net interest payments have been explored in a previous article in the Regional Economist: Rising Rates Impact Borrowing Costs for the U.S. Government, Too.

The primary deficit comprises mostly government spending and tax revenue, and both of these components depend on interest rates only to the extent to which interest rates affect the business cycle. Over two-thirds of government spending is related to entitlements and spending with social programs, and more than half of federal revenue originates in the personal income taxes. These types of instruments are known as automatic stabilizers and are designed in such a way that spending increases (falls) during recessions (expansions), and revenue falls (increases) during recessions (expansions), leading to countercyclical fiscal deficits (that is, fiscal deficits that rise during recessions and fall during expansions).

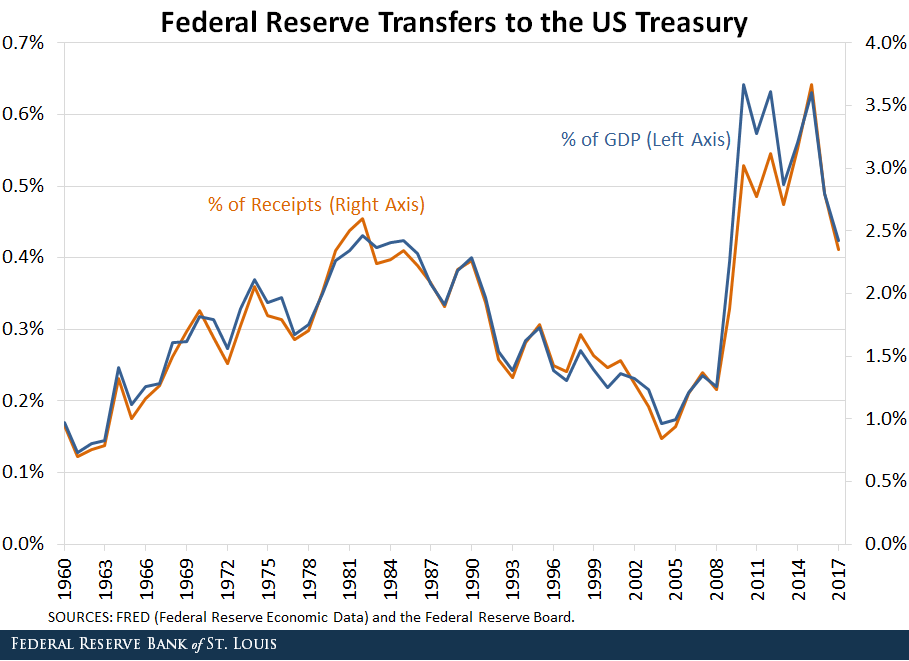

However, the Fed’s transfers to the Treasury depend more directly on interest rates. The Fed generates income while conducting monetary policy and exercising its financial regulation functions. This income must then be transferred to the U.S. Treasury and affects the federal deficit. The evolution of these transfers—as a share of current gross domestic product (GDP) and of total federal receipts—can be seen in the figure below.

Historically, these transfers have mostly fluctuated between 0.2 percent and 0.4 percent of GDP. They increased rapidly starting in 2009 and reached its record in 2015, In addition to the $97.7 billion in revenue mentioned earlier, the Fed also sent a one-time capital surplus of $19.3 billion, which was related to a change in how Fed dividends to member banks are computed. Transfers were historically high in 2015 even when this extraordinary surplus is not included. after which they seem to start declining.

Where Does the Fed’s Surplus Come from?

To understand this behavior, it is important to understand where the net income of the Fed comes from. In response to the financial crisis, the Fed launched a series of asset purchase programs that resulted in its balance sheet expanding from about $900 billion in mid-2008 to over $4.5 trillion in 2015. This expanded the Fed’s balance sheet from 6 percent of GDP to over 20 percent, as seen in the figure below.

Most of the purchased assets were agency-issued mortgage-backed securities, longer-term U.S. Treasury bonds and debt securities issued by government sponsored enterprises. All of these assets generate interest income, which explains why the Fed’s transfers to the Treasury increased.

As the Fed raises rates, its balance sheet has started to shrink, which helps to explain why transfers may be lower going forward.

Effects of Interest on Excess Reserves

Still, the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet is just one part of the story. Starting in 2008, the Fed also started paying interest on excess reserves held by banks. These asset purchase programs entailed the creation of an equal amount of reserves, on which interest was paid.While interest rates were low during this period, the amount of reserves was very large. This contributed to moderating the size of the transfers to the Treasury.

These transfers are likely to keep falling for two reasons:

- The rate of interest on excess reserves will likely increase as the federal funds rate target increases, which has been gradually increasing.

- The Fed is reducing the size of its balance sheet, thus reducing the interest income it receives on purchased securities.

It is, therefore, to be expected that these transfers return to their historical, lower levels.

Notes and References

1 The effects of the gradual increase in the federal funds rate target on government net interest payments have been explored in a previous article in the Regional Economist: Rising Rates Impact Borrowing Costs for the U.S. Government, Too.

2 Over two-thirds of government spending is related to entitlements and spending with social programs, and more than half of federal revenue originates in the personal income taxes. These types of instruments are known as automatic stabilizers and are designed in such a way that spending increases (falls) during recessions (expansions), and revenue falls (increases) during recessions (expansions), leading to countercyclical fiscal deficits (that is, fiscal deficits that rise during recessions and fall during expansions).

3 In addition to the $97.7 billion in revenue mentioned earlier, the Fed also sent a one-time capital surplus of $19.3 billion, which was related to a change in how Fed dividends to member banks are computed. Transfers were historically high in 2015 even when this extraordinary surplus is not included.

4 While interest rates were low during this period, the amount of reserves was very large.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Risky Are Government Intervention Programs?

- On the Economy: The Fed, Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

- On the Economy: How Might Increases in the Fed Funds Rate Impact Other Interest Rates?

Citation

Miguel Faria-e-Castro, ldquoFed Payments to Treasury and Rising Interest Rates,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 4, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions