How Much Does the U.S. Trade with China, Canada and Mexico?

With recent changes in U.S. trade policy—particularly towards China, Canada and Mexico—economists and policymakers alike have been trying to identify the potential impact of these changes on the U.S. economy. In previous posts, I have examined the role of imported intermediate inputs in the production of U.S. manufacturers, as well as the extent to which U.S. workers are involved in the production of goods sold overseas.

In this post, I investigate the importance of trade with China, Canada and Mexico relative to trade with the rest of the world. In particular, I used data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for 2017 to examine the composition of U.S. imports and exports across countries and product categories. Specifically, I used the OECD’s Bilateral Trade Database by Industry and End-Use

Potential Impact of Trade Barriers on Households and Firms

One concern is that if U.S. imports of certain types of goods are concentrated in countries towards which trade barriers are raised, then this might negatively impact households that consume such goods or firms that use such goods as intermediates to produce other goods.

Similarly, if U.S. exports of certain product categories are concentrated in countries towards which trade barriers are raised, then this might negatively impact workers and firms that produce such goods. The destination countries, for instance, could retaliate by raising trade barriers on imports of U.S. goods.

Imports Composition across Countries and Product Categories

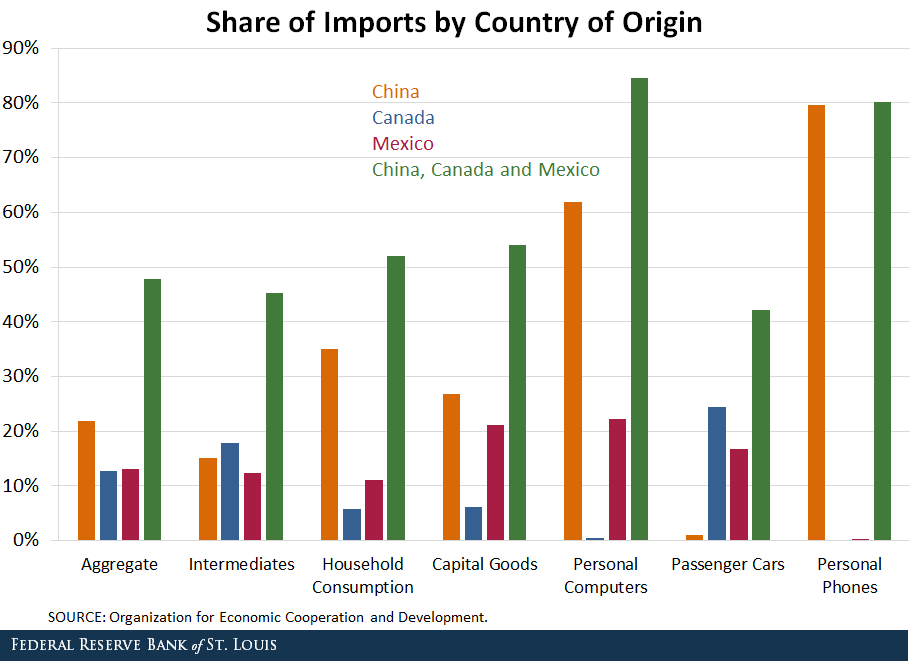

The figure below reports the import shares of goods from China, Canada and Mexico across different product categories.

First, U.S. imports of goods from China, Canada and Mexico accounted for a substantial share of aggregate U.S. imports. In particular, 22 percent of imports were purchased from China in 2017, while imports from Canada and Mexico each accounted for 13 percent. Thus, close to half of all U.S. imports came from these three countries.

Second, China is a particularly important supplier in particular product categories. For instance, 35 percent of all imports of household consumption goods were from China, while this was the case for 62 percent and 80 percent of imports of personal computers and personal phones, respectively.

Third, a significant fraction of imports of passenger cars were purchased from Canada and Mexico, with the three countries jointly accounting for 42 percent of total U.S. imports of these vehicles.

Finally, while none of these countries individually played a particularly crucial role in accounting for U.S. imports of intermediate inputs and capital goods, they jointly accounted for 45 percent and 54 percent, respectively.

These observations show that China, Canada and Mexico accounted for a very significant share of aggregate U.S. imports across key product categories. This evidence suggests that households, firms and workers that rely on goods imported from such countries may be hurt if the U.S. were to raise trade barriers on imports from these countries.

Households might be hurt by having to pay higher costs for imported goods. Firms might be hurt by having to pay higher costs for production inputs or by having to adjust production to use domestic alternatives. In either case, economic losses might result.

Exports Composition across Countries and Product Categories

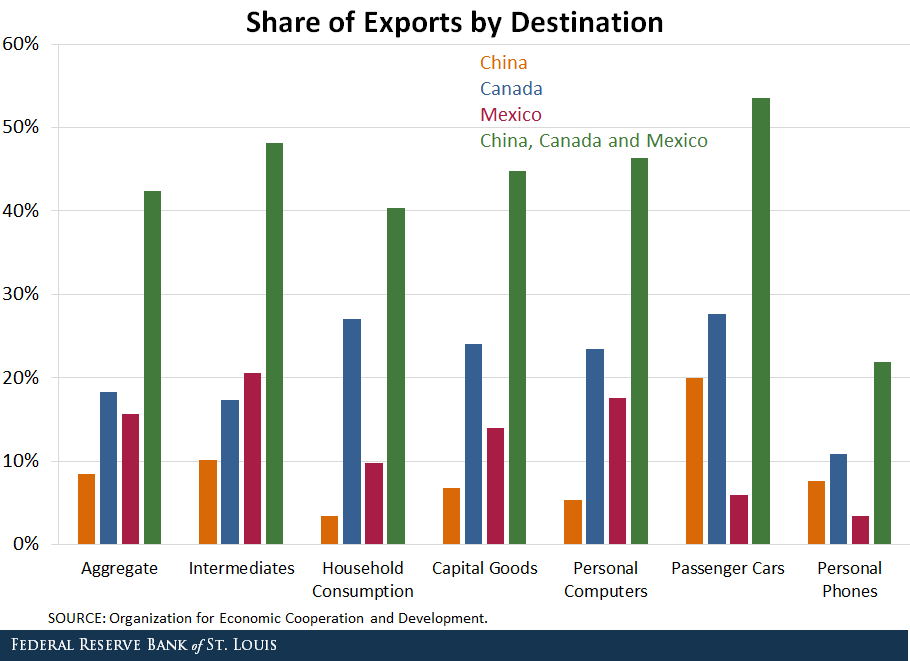

The figure below reports the export shares of U.S. goods to China, Canada and Mexico across different product categories.

As with imports, exports of goods to China, Canada and Mexico jointly accounted for a substantial share of aggregate U.S. exports:

- 8 percent of U.S. exports were shipped to China.

- 18 percent were shipped to Canada.

- 16 percent were shipped to Mexico.

Thus, exports to these three destinations accounted for 42 percent of aggregate U.S. exports.

China

In contrast to the case of imports, China was not a particularly important destination of U.S. exports. In addition to accounting for only 8 percent of aggregate U.S. exports, exports to China also accounted for 10 percent or less of U.S. exports of:

- Intermediates

- Household consumption goods

- Capital goods

- Personal computers

- Personal phones

The one exception was passenger cars: China accounted for 20 percent of U.S. exports of such vehicles.

These findings suggest that the impact of Chinese tariffs on imports of goods from the U.S. are likely to have a limited impact on the U.S economy on the whole.

Canada and Mexico

Exports to Canada and Mexico, on the other hand, were significantly larger across multiple product categories.

For instance, 17 percent and 21 percent of U.S. exports of intermediates were shipped to Canada and Mexico, respectively. Similarly, the U.S. shipped 24 percent and 14 percent of its exports of capital goods to Canada and Mexico, while the respective values for personal computers were 23 percent and 18 percent. Therefore, Canada and Mexico jointly accounted for a significant fraction of U.S. exports across several types of goods.

As in the case of imports, these observations show that China, Canada and Mexico play a fundamental role in accounting for U.S. exports of various types of goods. Thus, were these countries to raise trade barriers on imports of U.S. goods, then firms and workers that rely on exports to such destinations might be significantly affected.

USMCA and the Path Forward

The announcement of the United States – Mexico – Canada Agreement (USMCA) on Sept. 30 ensures the continuation of fluid access for U.S. goods in the Canadian and Mexican markets. Similarly, the agreement ensures that American households and firms continue to enjoy access to their Canadian and Mexican suppliers of goods.

Given the high dependence of aggregate U.S. trade flows on trade with Canada and Mexico, the recent announcement of the USMCA should allow the U.S. to avert the potentially negative impact that would have resulted from dissolving but not replacing the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Trade relations with China appear to be on less solid ground at the time that this post is being written. Yet, the relatively low share of U.S. exports shipped to China suggests that the potential damages inflicted by potential increases of Chinese tariffs on imports from the U.S. are likely to be limited.

Notes and References

1 Specifically, I used the OECD’s Bilateral Trade Database by Industry and End-Use.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Many Workers Make Goods That Are Sold Overseas?

- On the Economy: How Could Higher Tariffs Affect American Manufacturers?

- On the Economy: Tariff Increases and the Potential Economic Effects

Citation

ldquoHow Much Does the U.S. Trade with China, Canada and Mexico?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Oct. 9, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions