How Many Workers Make Goods That Are Sold Overseas?

With the ongoing changes to U.S. trade policy, countries are beginning to retaliate in kind. For instance, the U.S. raised tariffs on $46.3 billion of Chinese products on June 15. That same day, China raised tariffs targeting $44.9 billion of imports from the U.S. The value of imports affected is based on 2017 numbers. See Bown, Chad P.; Jung, Euijin; and Lu, Zhiyao (Lucy). “China’s Retaliation to Trump’s Tariffs.” Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 22, 2018. Similar actions are being taken or considered by other countries affected by the recent and ongoing increases in U.S. tariffs.

As U.S. exporters begin to face higher trade barriers for selling their goods across the world, they might need to respond by reducing their growth prospects or scaling down their operations. Not only might sales and profits be affected, but jobs might also be lost as U.S. exporters adjust their production decisions to the new economic environment.

In this post, I look at the sectoral composition of the jobs that might be negatively affected by the ongoing tariff retaliation by U.S. trade partners. In particular, I used data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for 2011 (the latest year available) to examine the distribution of U.S. jobs involved in the production of goods shipped overseas. For details, see the OECD’s Trade in Employment.

Jobs Working on Exported Goods

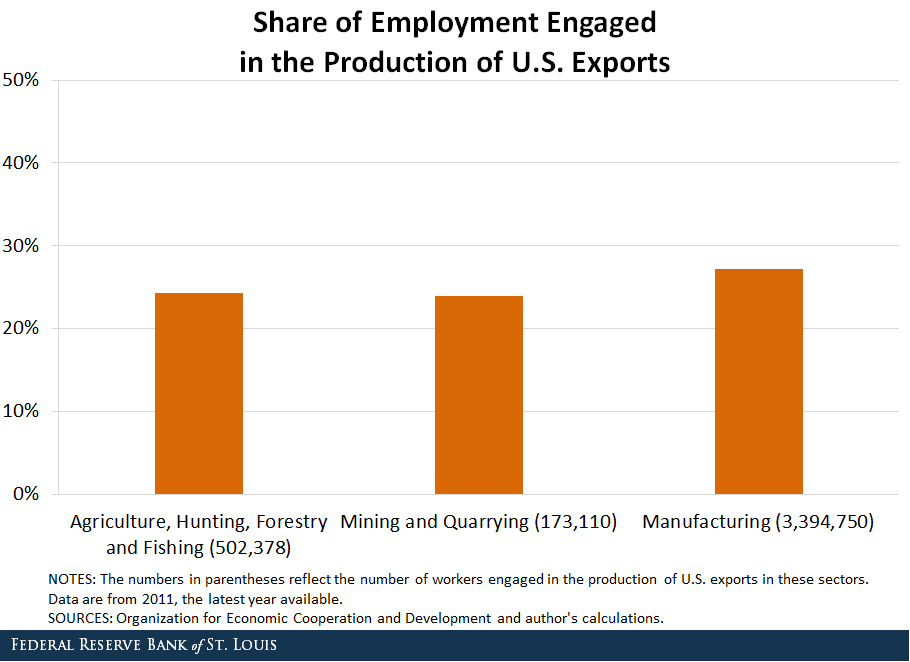

The figure below reports the share of workers involved in the production of goods sold internationally across three broad sectors of the economy. I found that approximately 25 percent of all workers employed in these three sectors produce goods that are sent abroad:

- Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing

- Mining and quarrying

- Manufacturing

These jobs amounted to around 4.1 million workers in total, with a majority of them in manufacturing.

Who Gets the Goods?

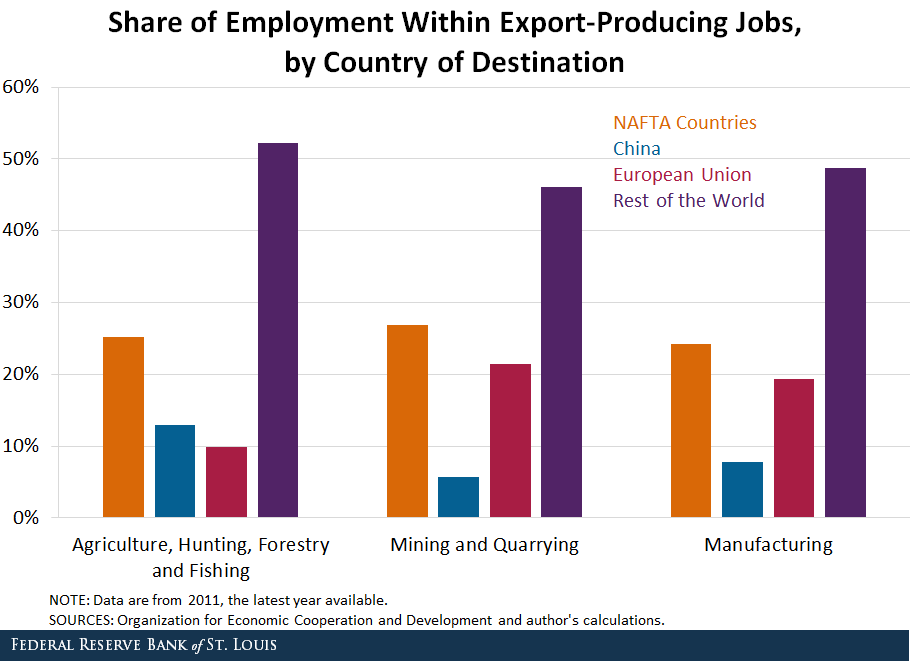

The figure below examines the composition of workers involved in the production of U.S. exports by destination. I found that exports to NAFTA countries accounted for around 25 percent of all workers employed by exporters in each sector. Exports to China accounted for 6 percent, 8 percent and 13 percent of workers involved in the production of exports of mining, manufacturing and agriculture, respectively.

In contrast, the share of workers involved in exports to the European Union differed markedly across sectors: While the share was 10 percent in agriculture, it was approximately 20 percent in mining and manufacturing. Workers involved in the production of exports sold to the rest of the world accounted for the rest, around 50 percent in each sector.

Manufacturing Industries and Exported Goods

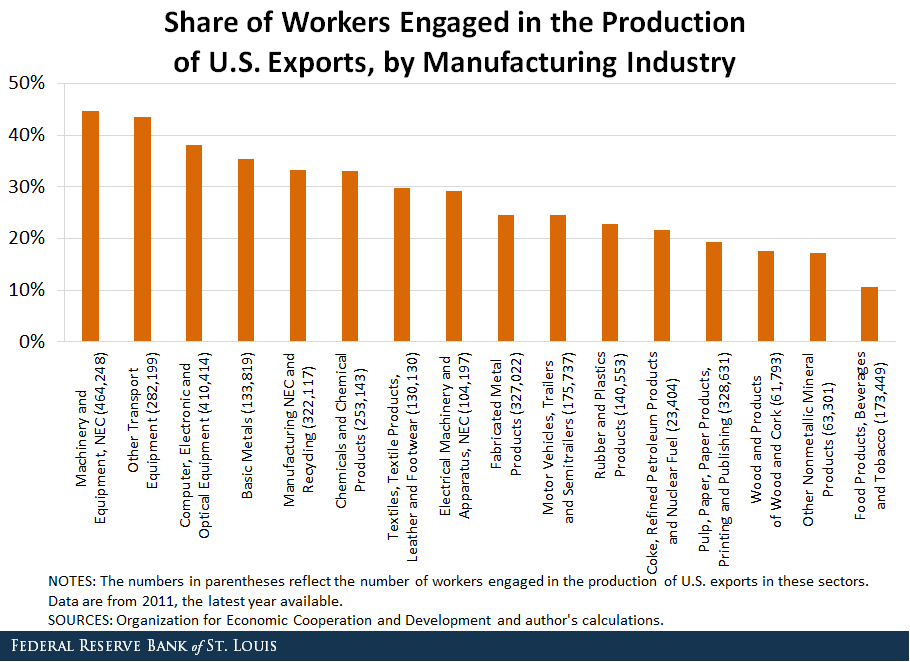

Finally, in the figure below, I examined the composition of workers involved in the production of U.S. exports across different manufacturing industries. On one end, there were sectors that employed more than 35 percent of their workforce in the production of goods sold internationally:

- Machinery and equipment

- Other transport equipment

- Computer, electronic and optical equipment

- Basic metals

On the other end, there were industries in which less than 20 percent of their workers were involved in the production of goods sold overseas:

- Pulp, paper, paper products, printing and publishing

- Wood and products of wood and cork

- Other nonmetallic mineral products

- Food products, beverages and tobacco

This evidence shows that a considerable number of U.S. workers are involved in the production of goods sold overseas. This suggests that several jobs might be at risk as U.S. trade partners raise trade barriers on American goods.

The evidence also shows that while workers in agriculture, mining and manufacturing are similarly prone to be affected, the vast majority of jobs employed by U.S. exporters are in the production of manufactured goods. Within manufacturing, however, industries differ in their exposure to potential tariff hikes by U.S. trade partners.

Further research needs to be conducted to quantify the extent to which higher tariffs on exporters of U.S. goods might affect employment and economic activity.

Notes and References

1 The value of imports affected is based on 2017 numbers. See Bown, Chad P.; Jung, Euijin; and Lu, Zhiyao (Lucy). “China’s Retaliation to Trump’s Tariffs.” Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 22, 2018.

2 For details, see the OECD’s Trade in Employment.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Could Higher Tariffs Affect American Manufacturers?

- On the Economy: Tariff Increases and the Potential Economic Effects

- On the Economy: How Do Americans Feel about NAFTA?

Citation

Fernando Leibovici, ldquoHow Many Workers Make Goods That Are Sold Overseas?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 9, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions