How Do Rising Short-Term Rates Affect Uncle Sam?

When short-term interest rates rise, they affect borrowing costs for everyone, including the U.S. government. So how do these higher rates affect the borrowing costs of Uncle Sam?

Economist Miguel Faria-e-Castro and Research Associate Asha Bharadwaj looked at the complex relationship between short-term interest rates and the federal government’s borrowing costs in a recent Regional Economist article.

Short-term interest rates are rising because the Federal Reserve has been increasing its policy rate—the federal funds rate target—as part of the normalization of monetary policy. The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which banks lend to each other overnight.

“The government’s cost of borrowing is likely to become an increasingly important issue,” the authors wrote. “The federal debt stands at its highest level since the 1940s, having exceeded 103 percent of annual gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of 2017.”

What Determines Borrowing Costs?

The authors pointed out that interest payments are a product of both the interest rate and the total stock of federal debt. Assuming all else is constant, borrowing costs tend to increase when the amount of federal debt is higher or when the Fed raises interest rates.

However, this relationship is nonlinear, they noted.

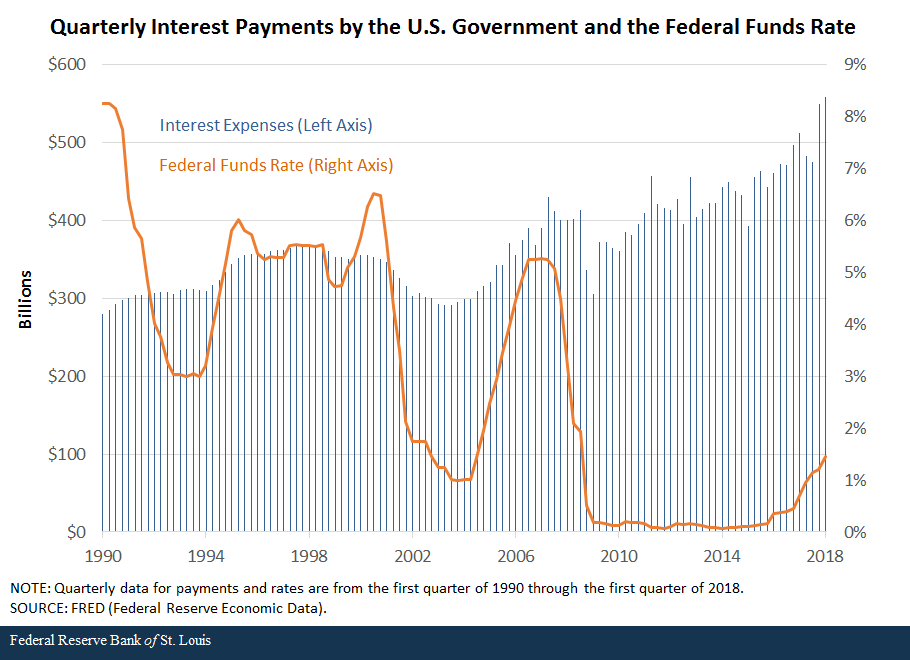

The figure below shows the relationship between interest payments by the federal government and the federal funds rate since 1990.

As the chart shows, interest payments don’t march in lockstep with the federal funds rate. Faria-e-Castro and Bharadwaj pointed out two reasons for this:

- The stock of debt matters. Though interest rates were roughly constant after 2009, interest payments rose due to increased debt levels that were the result of government-financed stimulus programs and interventions in the financial sector following the Great Recession.

- The Fed’s policy rate primarily affects short-term interest rates, but the Treasury borrows at many different maturities, which pay different interest rates. While influenced by the federal funds rate, these longer-term rates are also affected by other factors.

Three types of instruments with various maturities—Treasury bills, Treasury notes and Treasury bonds—made up almost 90 percent of marketable federal debt outstanding as of March 2018. Other types of marketable debt securities are Treasury inflation-protected securities and floating-rate notes. Marketable debt securities account for over 73 percent of total federal debt outstanding. The remainder—nonmarketable debt—is mostly accounted for by intragovernmental holdings and is ignored for the purposes of this blog post.

Treasury bills are typically issued with maturities of one year or less. Because they have very short maturities, the return on these instruments will typically be close to the policy rate set by the Fed, less so as the maturity increases.

Treasury notes are issued at two-, three-, five-, seven- and 10-year maturities, while Treasury bonds are issued with a maturity of 30 years.

“When deciding to invest in these securities, as opposed to ones with shorter maturities, investors take into account the fact that they are locking their funds into an asset that pays a fixed interest rate for a longtime horizon,” the authors wrote.

The Term Premium

So what determines the interest rate on longer-term Treasury debt? Investors will demand something called a “term premium,” which is extra compensation for holding longer-term debt. The authors estimated the term premium as the difference between the interest rates of the 10-year Treasury note and the one-year Treasury bill.

The term premium can depend on expectations of future macroeconomic indicators, such as economic growth and inflation, and on other factors, such as demographics, according to Faria-e-Castro and Bharadwaj.

“The term premium fluctuates over the business cycle and is generally positive (long-term rates are greater than short-term rates) for the reasons explained above,” they said.

While long-term rates tend to move up and down with short-term rates, movements in the term premium are crucial in determining whether long-term rates will move more or less than short-term rates, according to the authors.

Conclusion

The maturity structure of federal government debt, the stock of federal debt and the term premium are reasons why the relationship between rising interest rates and borrowing costs for the government is nonlinear, according to Faria-e-Castro and Bharadwaj.

The term premium “is especially relevant because longer-term securities (those with a term over five years) represent over 70 percent of marketable federal debt outstanding,” they wrote.

Notes and References

1 Other types of marketable debt securities are Treasury inflation-protected securities and floating-rate notes. Marketable debt securities account for over 73 percent of total federal debt outstanding. The remainder—nonmarketable debt—is mostly accounted for by intragovernmental holdings and is ignored for the purposes of this blog post.

2 The authors estimated the term premium as the difference between the interest rates of the 10-year Treasury note and the one-year Treasury bill.

Additional Resources

- Regional Economist: Rising Rates Impact Borrowing Costs for the U.S. Government, Too

- On the Economy: How Might Increases in the Fed Funds Rate Impact Other Interest Rates?

- On the Economy: Fed Payments to Treasury and Rising Interest Rates

Citation

ldquoHow Do Rising Short-Term Rates Affect Uncle Sam?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 13, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions