Global Debt Is Rising, Especially in Emerging Economies

The world has become used to cheap credit. And the increase in borrowing by emerging economies could pose a risk as monetary policy normalizes.

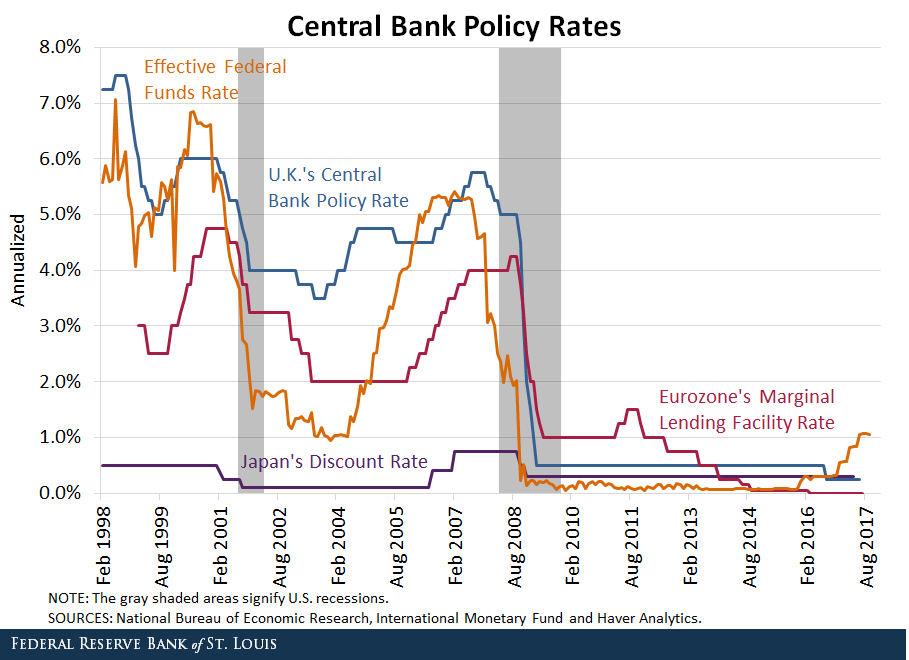

In response to the most recent recession, central banks around the world decreased their main policy rates to almost zero, as seen in the figure below.

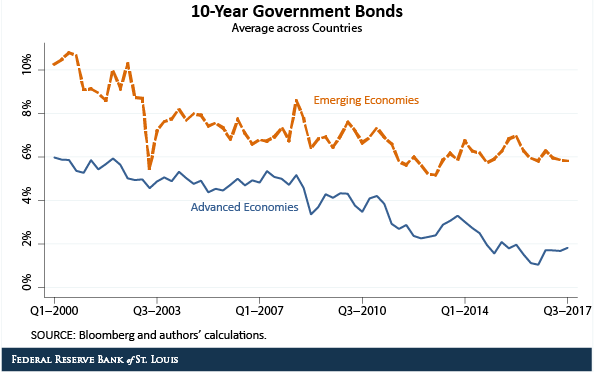

The next figure shows that long-term interest rates also declined in both advanced and emerging economies.

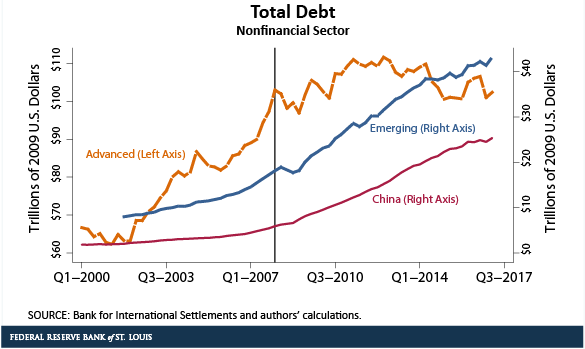

The downward trend in short-term and long-term interest rates has made borrowing cheaper over time. As a result, global debt has increased substantially since 2007.

Increasing Global Debt

According to Bank for International Settlements (BIS) data, total debt of the nonfinancial sector (that is, households, government and nonfinancial corporations) amounted to $145 trillion in the first quarter of 2017, an increase of 40 percent since the first quarter of 2007.1

Most of this increase has been driven by an increase in total debt in emerging economies, especially in China, as seen in the following figure.

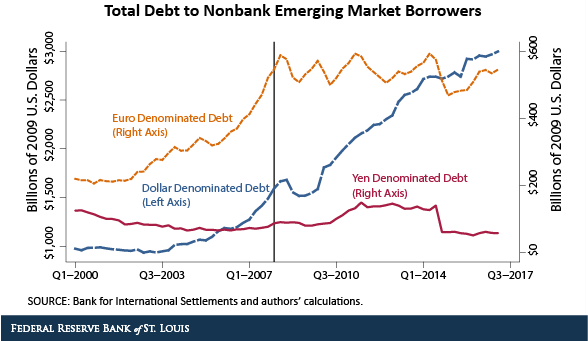

Furthermore, emerging economies have borrowed heavily in foreign currency, mainly in U.S. dollars, shown in the figure below.

According to the BIS, total dollar-denominated debt outside the U.S. reached $10.7 trillion in the first quarter of 2017, and about a third of this debt is owed by the nonfinancial sector of emerging economies.2

Risks of Rising Global Debt

Analysts have stressed that the rapid accumulation of debt in emerging economies could pose risks for the global economy in the presence of U.S. monetary policy normalization.

Market expectations of a rapid increase in the policy rate and the reduction of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet could lead to higher borrowing costs and an appreciation of the U.S. dollar. This, in turn, would increase the cost of refinancing debt in emerging economies.

If these risks materialized, there could be an increase in the demand for safe assets, particularly U.S. Treasuries. This would lead to a decrease in long-term rates. In times of monetary normalization, the yield curve would flatten, and banks profitability could be eroded.

Treasuries and Current Account Balances

Furthermore, the amounts of U.S. Treasuries in emerging markets (as part of their foreign reserves) are closely associated with their current account balances. For example, the Chinese central bank increased its foreign reserves substantially by running large current account surpluses in the 2000s. However, the amount of these foreign debts began declining when current account surplus decreased.3

Addressing Rising Global Debt

To maintain a relatively large holding of U.S. Treasuries, one possible scenario for the emerging economies is to depreciate the value of their currency. In that case, the U.S. and other advanced economies could face challenges reducing current account deficits.

Rapid increases in leverage in emerging economies could pose risks for advanced economies if the cost of refinancing the debt increased more rapidly than expected. Even expectations of rapid increases in interest rates could lead to reversals of capital flows out of emerging markets and an increase in demand for safe assets, leading to negative consequences for advanced economies.

Notes and References

1 Bank for International Settlements, “Credit to the non-financial sector” statistics description. Updated Sept. 17, 2017. Total debts accounts for loans, debt securities (bonds and short-term paper), and currency and deposits. We converted the reported numbers into constant 2009 U.S. dollars.

2 Richter, Wolf. “China is binging on dollar-denominated debt.” Business Insider, Oct. 12, 2017, and Whitehouse, Mark. “The World Can’t Stop Borrowing Dollars.” Bloomberg, Sept. 25, 2017. Number cited directly from the article.

3 Santacreu, Ana Maria and Zhu, Heting. “China’s Foreign Reserves Are Declining. Why, and What Effects Could This Have?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis On the Economy Blog, Oct. 3, 2017.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: China’s Foreign Reserves Are Declining. Why, and What Effects Could This Have?

- On the Economy: How Did China Build Up Its Reserves?

- On the Economy: Why Does China Have Large Foreign Exchange Reserves?

Citation

Ana Maria Santacreu and Heting Zhu, ldquoGlobal Debt Is Rising, Especially in Emerging Economies,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 20, 2017.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions