The Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax and the Value of the Dollar

The destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT) is currently under consideration in the House of Representatives. Such a tax could cause a significant change in the inflation-adjusted value of the U.S. dollar. So, what are the possible repercussions?

Features of the Proposed Tax

A laudable goal of the DBCFT is to reduce the U.S. corporate tax rate schedule, which is one of the highest in the world. The proposed DBCFT would have three important features:

- It would replace the current top marginal corporate profits tax rate of 35 percent with a rate of 20 percent.

- It would allow businesses to immediately deduct all expenses—including capital investments and labor—from revenue.

- It would be “border adjusted” to tax goods by where they are purchased rather than where they are produced. That is, the tax would be added to imports and rebated on exports.

Possible Impact on the U.S. Dollar

Because the taxes on imports and subsidies for exports would make U.S. goods less expensive relative to their foreign counterparts, economists and business analysts expect the U.S. dollar to appreciate by 25 percent in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms.

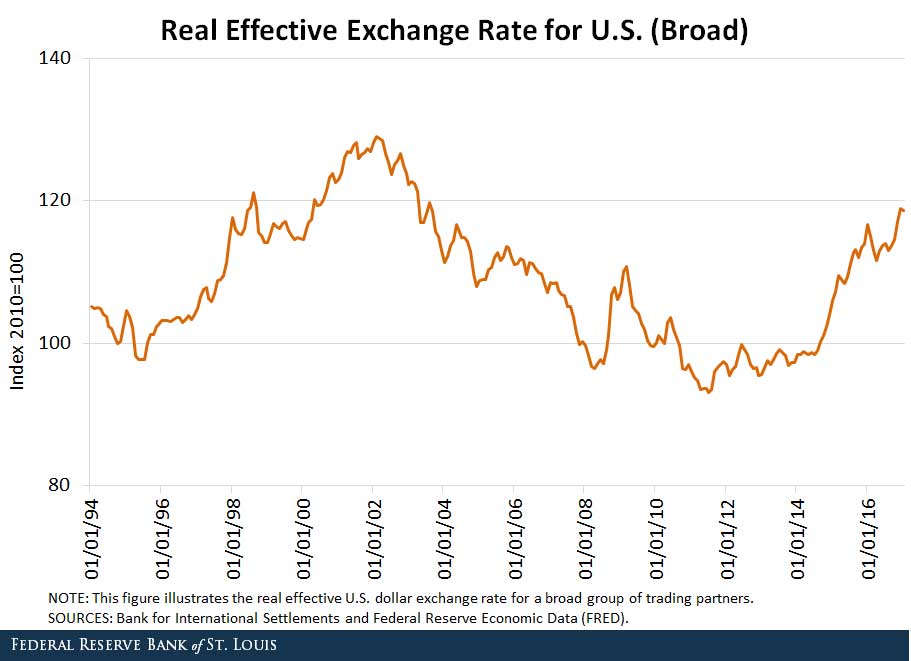

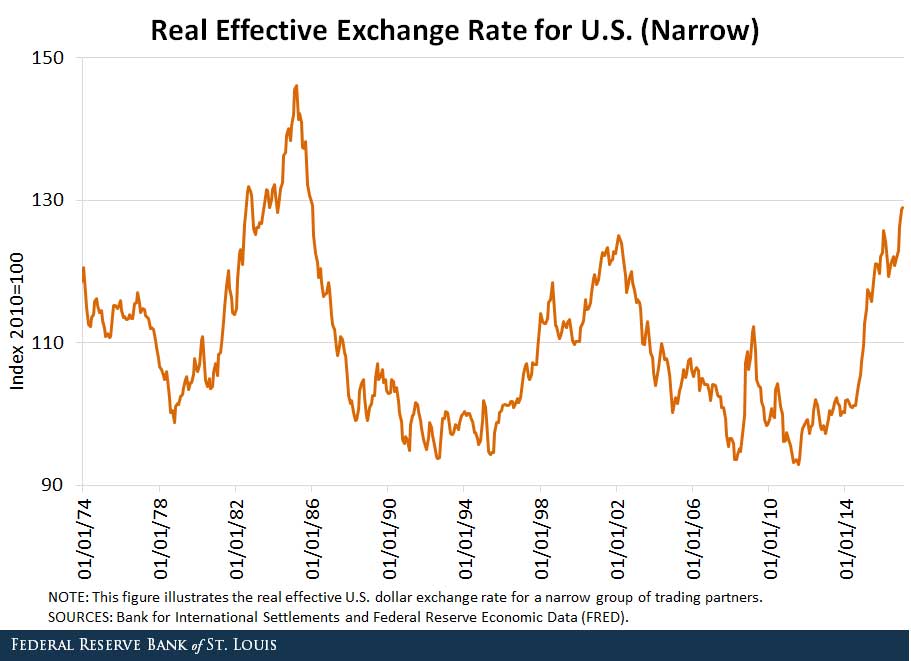

The figures below show that a 25 percent change in the real dollar exchange rate would be very large in historical terms. The total variation (maximum minus minimum) in the broad index, for example, is only about 35 percent.

Analyses of the DBCFT have focused on its effects on the tradable goods sector and tax revenues and on the likely change in the real exchange rate. There has been little consideration of the international and financial market effects of a large exchange rate adjustment, despite the potentially substantial size of such effects.

The Potential Effects on Markets

Any analysis of the change in the exchange rate should begin by noting that these changes are likely to be gradual, occurring as expectations change about how likely the DBCFT is to be adopted.

Markets, however, will not wait to price in the implications of adoption until the legislation passes or until the law takes effect. The reason for that is that an expectation of a jump in an asset prices would create a profit opportunity that would be bid away by foreign exchange market participants.

So, one should never expect a future jump in asset prices unless there is a lot of risk involved. Asset prices do jump, but those jumps are not widely expected ahead of time.

After the dollar begins gradually appreciating but before the taxes and transfers become law, U.S. firms will benefit or suffer from the real appreciation in the dollar because U.S. goods will become more expensive—at least until the taxes/subsidies take effect—relative to their foreign counterparts:

- Firms that import intermediate goods will benefit.

- Firms that compete directly with foreign firms in international markets will suffer, at least temporarily.

This is a potentially serious issue because only half of U.S. firms hedge their currency risk.1

Effect on Firms with Foreign Assets and Liabilities

The appreciation of the dollar will also affect the value of U.S. firms with foreign assets and liabilities because those will be revalued in dollars as the value of the dollar changes. U.S. firms with positive (negative) net foreign assets will lose (gain) value.

A large real appreciation of the dollar could create a serious problem for the many developing countries that fix their exchange rates to the dollar in some way. It would require these countries to either abandon or adjust those nominal exchange rate pegs—which could cause local inflation—or allow their currencies to appreciate very substantially against those of their trading partners.

The table below shows that many countries currently have exchange rates that are managed with respect to the dollar.

| Exchange Rate Arrangements Involving the U.S. Dollar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Pegs | Soft Pegs | ||||

| No Separate Legal Tender | Currency Board | Conventional Peg | Stabilized Arrangement | Crawling Peg | Other Managed Arrangement |

| Ecuador | Djibouti | Aruba | Guyana | Honduras | Cambodia |

| El Salvador | Hong Kong SAR | The Bahamas | Lebanon | Nicaragua | Liberia |

| Marshall Islands | Antigua and Barbuda | Bahrain | Maldives | ||

| Micronesia | Dominica | Barbados | Trinidad and Tobago | ||

| Palau | Grenada | Belize | |||

| Panama | St. Kitts and Nevis | Curacao and Sint Maarten | |||

| Timor-Leste | St. Lucia | Eritrea | |||

| Zimbabwe | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | Iraq | |||

| Jordan | |||||

| Oman | |||||

| Qatar | |||||

| Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Turkmenistan | |||||

| United Arab Emirates | |||||

| Venezuela | |||||

| SOURCE: International Monetary Fund. | |||||

| Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis | |||||

- Eight countries are fully dollarized and have no separate legal tender.

- Eight other countries have currency boards.

- 15 countries have conventional exchange rate pegs.

- Eight more countries have other managed arrangements, such as crawling pegs.

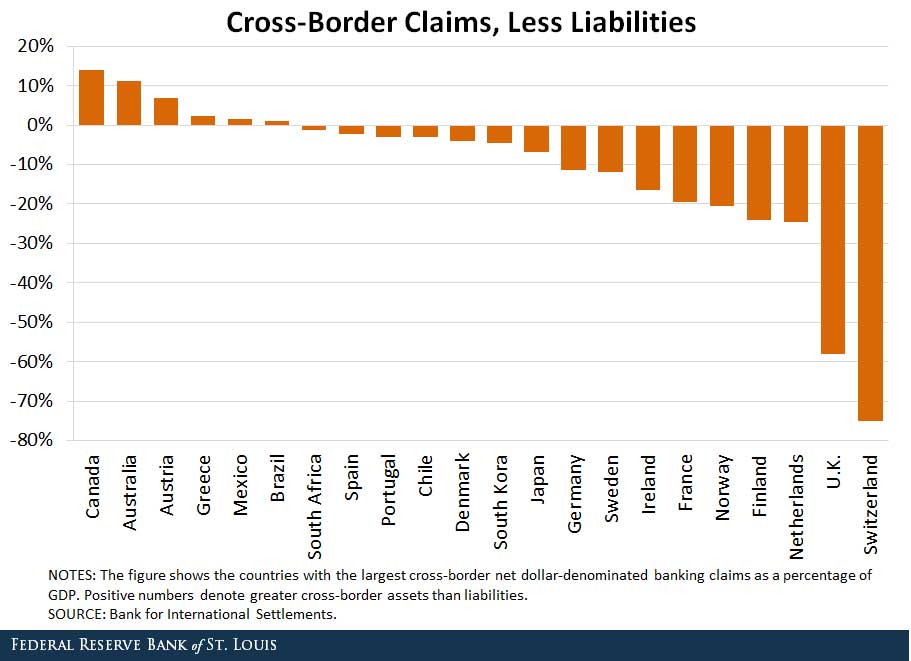

An appreciation of the dollar would also have wide ramifications for the many banks and firms that use the dollar for cross-border lending. The figure below illustrates the magnitude of net cross-border dollar-denominated claims as a percentage of GDP using data from the Bank for International Settlements' locational banking statistics.

Countries with positive (negative) cross-border banking claims would benefit (lose) from a dollar appreciation, at least along this limited dimension.

The takeaway is that the presence of nominal contracts, such as bonds and/or bank lending, means that a large revaluation of the dollar—even if it compensates for taxes and subsidies—would likely produce many arbitrary winners and losers and could have unintended consequences.

Notes and References

1 See Ryan, Vincent. “Only Half of Companies Hedging Currency and Other Risks.” CFO Magazine, Oct. 17, 2013.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Trading Ideas between Countries

- On the Economy: Which States Account for Our Trade Deficit with Mexico?

- On the Economy: The Exports of Innovative Countries

Citation

Christopher J. Neely, ldquoThe Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax and the Value of the Dollar,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 8, 2017.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions