What Does the Market Say about the Presidential Election?

In recent months, all eyes have been on the presidential race between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Many people have been watching the polls to get a feel for the likely outcome, partly to make optimal economic decisions.

Unfortunately, polling is complex, perhaps more so this year than in previous campaigns. How many people in each demographic or political group should be sampled? Should one poll only registered voters or likely voters? How should the poll handle third-party candidates or undecided voters?

Polling Via Financial Markets

Because polls differ on the best procedures, it is not at all clear which polls to trust. The behavior of financial markets provides an alternative source of information that complements polls.

For example, there have been several columns on the behavior of asset markets during the recent debate on Sept. 26. One such column in The Wall Street Journal interpreted the appreciation of the peso and a decline in gold prices during the most recent debate as indicating that market participants believed that the debate improved Mrs. Clinton’s standing.1 This type of analysis is known as an “event study” and is often used to infer the effect of particular events or announcements on asset prices.

Issues with Reading Market Activity

Watching financial markets around specific events gives some idea how the market reacts to those events—i.e., who was helped or harmed by an event—but it doesn’t tell us who is ahead or what the longer trends have been. Neither can we look at longer trends in asset prices, such as the peso or gold, to tell us with any certainty who is gaining or losing, because asset prices are influenced all the time by incoming news of all sorts.

For example, the value of the Mexican peso is influenced by incoming news about Mexican monetary policy, the Mexican business cycle and Mexican elections. Only in a short window around particularly important events, such as the presidential debate, can we ascribe the reaction of asset prices to the event. In other words, most standard financial markets offer only limited information about longer trends in the election.

Financial Markets for the Election

There are markets, however, that exist to directly assess the likelihood of electoral outcomes.2 The Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM), operated by the University of Iowa Tippie College of Business, runs a market that directly assesses the likelihood of election outcomes. It provides participants the opportunity to buy and sell securities with payoffs that depend on the outcome of elections.3

The idea behind the market is that one can purchase a security that pays off if a particular candidate wins the election. The price of this security should directly reflect the probability of this event. If the security is priced too low compared to the probability, market participants will presumably try to buy more of that security, bidding up the price until it reflects the participants’ assessment of the likelihood of the given candidate winning.

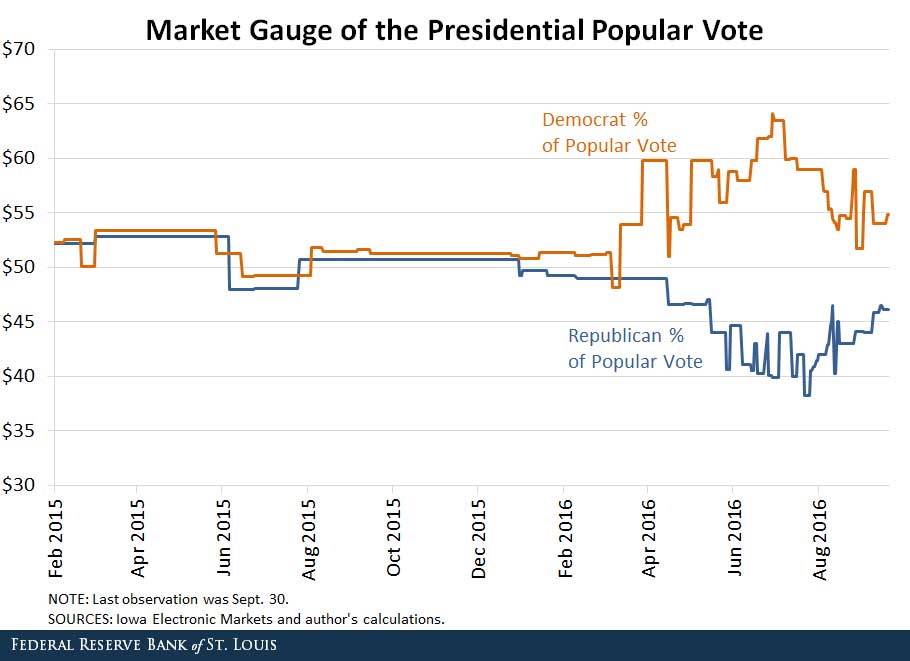

Similar securities pay off in proportion to the candidates’ share of the popular vote, so the prices of these latter securities are expected to reflect the predicted share of the popular vote.

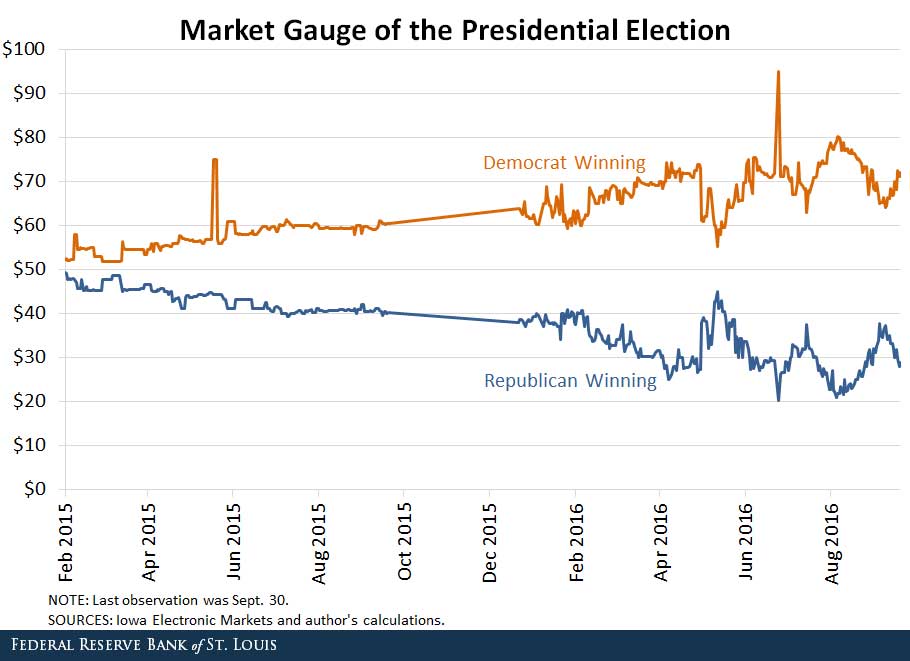

The first chart below shows the prices of two securities. The first pays off in case of a Democrat party victory and the second pays off in case of a GOP victory. The chart shows that there was a 70 percent chance that the Democrat candidate will win the presidency, as of Sept. 30. The second chart shows that the market expected the popular vote margin to be about 52 to 46 percent.

These markets are useful tools to aggregate information from many participants—“the wisdom of crowds”—because the participants must risk money to express their views, making it less likely that they will act frivolously.

One potential problem is that the IEM is relatively small. However, even a small market can accurately reflect a broad base of information if knowledgeable investors can easily enter the market to bid prices to more realistic levels.

The IEM is not an independent source of information from polls. Indeed, it is very likely that much of the information in the IEM prices likely comes from polls. The IEM’s advantage over polls is that participants have a monetary incentive to analyze the information in many polls and other data, to account for possible biases or bad procedures and to distill all available information into a price that reflects their considered view of the most likely outcome.

Notes and References

1 Russolillo, Steven. “Presidential Debate: Financial Markets Declare Winners and Losers.” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 27, 2016. Bizarrely, the asset price graphs on the page show the most recent 24 hours of data, rather than showing the prices at the time of the debate.

2 International betting establishments run some similar markets. One can place a bet on the outcome of the election, and the odds on such a bet can be used to assess the “risk-neutral” probability of the outcome. A risk-neutral probability is the probability that would make a risk-neutral trader indifferent between buying and selling the security. For example, if the Green Bay Packers are 2:1 favorites over the Minnesota Vikings, the risk-neutral probability of a Packer victory is 66.67 percent. We can’t say that this is necessarily the real probability because there could be a risk premium associated with a bet on the Packers-Vikings game.

3 In the interest of full disclosure, I worked for the Iowa Electronic Markets about 25 years ago.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: What Will Inflation Be over the Next Year?

- On the Economy: Was the Great Moderation Simply on Vacation?

- On the Economy: Aging Populations May Mean Lower Economic Growth

Citation

Christopher J. Neely, ldquoWhat Does the Market Say about the Presidential Election?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Oct. 6, 2016.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions