Will Real Yields Decline Further if Inflation Rises?

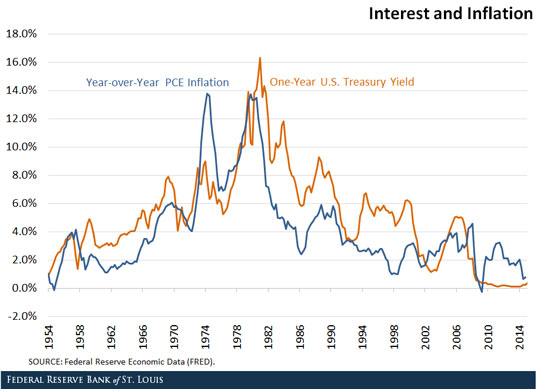

The most striking property of nominal interest rates in the U.S. in the post-Korean War period is their long climb up to and down from a peak of about 16 percent in 1981, as shown in the figure below.

The conventional explanation for this secular dynamic is that loose monetary policy in the late 1960s and 1970s led to rising inflation and inflation expectations. In turn, bondholders demanded higher yields (lower bond prices) as compensation for the expected loss of purchasing power associated with higher inflation.1 Tight monetary policy initiated in the early 1980s had the opposite effect.

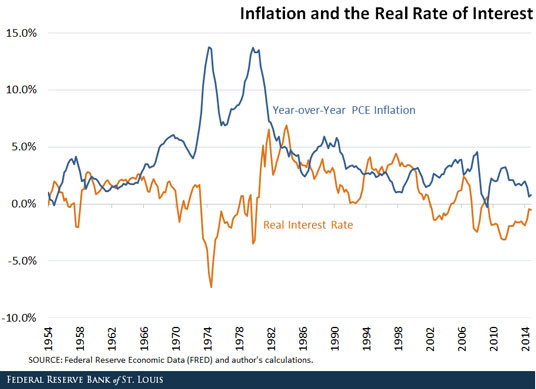

If inflation follows something close to a random walk, then realized inflation (plotted as the blue line in the figure above) serves as a reasonable proxy for one-year-ahead inflation expectations. The difference between the one-year nominal bond yield (the orange line in the figure above) and expected inflation then gives us a measure of the expected real rate of interest—the inflation adjusted return on U.S. Treasury debt. The figure below plots the inflation rate alongside the real rate of interest.

Many commentators have noted that the real interest rate is presently very low by historical standards. But as the figure above reveals, this is not the first time that real bond yields have been so low. In particular, the real interest rate was negative for much of the 1970s. (It is also interesting to note that the real interest rate was unusually high in the early 1980s.)

In a 1983 paper, Joel Fried and Peter Howitt argued that the observed relationship between inflation and the real interest rate is consistent with an economic theory that recognizes the liquidity value of U.S. Treasury debt.2 When inflation is high, the real rate of return on money is low. One should expect that the real return on close money substitutes would follow suit. The converse should hold true in a low-inflation regime, as experienced during the transition from high to low inflation in the early 1980s.

The preceding explanation, however, cannot account for real interest rate behavior since 2000. Inflation has remained relatively low and stable for more than 25 years. Yet the real return on U.S. Treasury debt declined into negative territory.

Evidently, there are factors other than expected inflation that determine the value of U.S. Treasury debt. Nominally safe assets like U.S. government bonds are valued throughout the world as high-grade collateral in lending arrangements and as a (relatively) safe store of value in private and public savings funds. Recent changes to financial regulations have also contributed to the demand for safe assets. If calls for higher inflation and inflation targets are heeded, then the implication here is that real yields are likely to decline even further.

Notes and References

1 Bonds are a promise to future money, so what matters to the bondholder is the purchasing power of the future money.

2 Fried, Joel; and Howitt, Peter. “The Effects of Inflation on Real Interest Rates.” American Economic Review, December 1983, Vol. 73, Issue 5, pp. 968-80.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Predicting the Impact of Oil Prices on Inflation

- On the Economy: Has the Phillips Curve Relationship Broken Down?

- On the Economy: Why Do Job Finding Rates Fall the Longer Someone Is Unemployed?

Citation

David Andolfatto, ldquoWill Real Yields Decline Further if Inflation Rises?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 5, 2015.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions