Career Switching Is Occurring Less Often, not More

In “Career Opportunities” on their eponymous album, the Clash dismiss an array of careers. Among other occupations, guitarist Mick Jones and lead singer Joe Strummer hate the army, the Royal Air Force and the civil service and apparently don't much care for making tea at the BBC. In a famous line from the song, Jones also bemoans his previous occupation as a mail clerk: He “won't open letter bombs for you.” Luckily, they found careers as punk rock pioneers instead.

This process of switching occupations until settling into a career is quite common in the U.S. But it seems that people are switching careers less often than before.

The conventional wisdom is that we switch occupations more often than previous generations. For a while, this was true. People were indeed switching occupations at an increasing frequency through the 1970s and 1980s, as was well documented by Gueorgui Kambourov and Iourii Manovskii.1 But at some point in the mid-1990s, this trend reversed, and occupational mobility has been falling since.

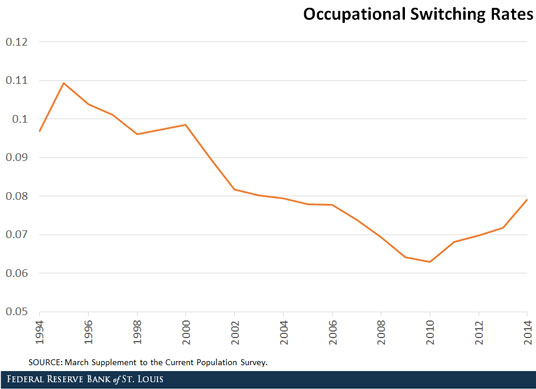

To illustrate this trend, we measured occupational switching at an annual frequency using the March Supplement to the Current Population Survey (CPS) from 1994 through 2014. Reading the figure below requires some care because it is somewhat difficult to measure occupational switching. In part, this is because an occupation is a nebulous category, and so counting a switch requires one to draw borders. For example, did an occupation switch occur if someone moved from teaching high school history to teaching government? Or do only more dramatic shifts count, such as a teacher becoming an administrator?

The CPS categorizes occupations at various levels of aggregation, some of which combine all subject teachers and others which distinguish. For the figure below, we use a level of aggregation which distinguishes dance teachers from social studies teachers, but not history teachers from economics teachers.2 Despite the difficulties associated with measuring switches, they will mostly affect the level of the switching rate. But, if these problems are constant over time, they will not affect the trend.

From its peak in 1995 to the trough in 2010, the rate nearly halved, though it has recovered some since the end of the Great Recession. This decline is echoed in other forms of labor mobility, such as employer switching and industry switching.

The meaning behind this time series, however, is uncertain. We have good evidence that people tend to switch into occupations that better use their skills, and so a decline in mobility may exacerbate the mismatch of talents.3 On the other hand, the decline may indicate that people are doing a better job of finding a good match in the first place.

While both explanations would be consistent with the decline in occupational mobility, they have drastically different implications. In the first scenario, Joe Strummer might still be called John Mellor. In the second, the Clash might have found each other earlier and had bit more time to learn how to play their instruments.

Notes and References

1 Kambourov, Gueorgui; and Manovskii, Iourii. “Rising Occupational and Industry Mobility in the United States: 1968-97,” International Economic Review, February 2008, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 41-79.

2 Another challenge is that some people may classify themselves differently from year to year despite holding the same job. For example, an economics professor may consider himself an economist one year and a professor of social sciences in another year. The March Supplement of the CPS helps in this regard by asking for the respondent’s current occupation and his occupation the previous year. However, this poses another challenge: We may note that a change has occurred, but we don’t know exactly when it occurred. Therefore, it is not strictly correct to interpret the switching rate in the figure as an annual rate.

3 Guvenen, Fatih; Kuruscu, Burhanettin; Tanaka, Satoshi; and Wiczer, David. “Multidimensional Skill Mismatch,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21376, July 2015.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Does Moving for a Job Mean Higher Wages?

- On the Economy: What Sitzfleisch Has To Do with Wages

- On the Economy: Does a Falling Unemployment Rate Imply Rising Wages?

Citation

David G Wiczer, ldquoCareer Switching Is Occurring Less Often, not More,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 24, 2015.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions