What Sitzfleisch Has To Do with Wages

Quincy Jones, who produced the exemplary music video for Michael Jackson’s hit Thriller, tried to describe the key to Jackson’s success. According to Jones, Jackson had an incredible ability to “be emotionally ready to put as much energy into it as it takes to make it right.”1

English has borrowed a lovely German word for this characteristic: sitzfleisch. It is the “power to endure or to persevere in an activity; staying power.”2 The word’s etymology refers to the flesh one sits on; it is alluding to one’s ability to stay seated for the long hours necessary to “make it right,” and also to perfectly choreograph every last hip thrust and moonwalk. Data show that sitzfleisch has market rewards even for those of us who are not the King of Pop.

How can we measure this advantage of persevering at a task, at staying seated until the task’s conclusion? It turns out that the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) includes a measure. The U.S. military designed this series of tests to help place new soldiers into jobs in the armed forces. Many of the tests cover straightforward topics such as “Word Knowledge.” However, one test stands out as peculiar: “Coding Speed.” Test-takers match words with numbers from a list in accordance with another separate key. This is a tedious exercise to do over and again, and returning and checking one’s answers is a true test of stamina.

The 1979 cohort of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth provides a way for measuring potential connections between performance on the ASVAB and future earnings, as this group’s test scores, subsequent earnings and labor force status are reported. I restricted the sample to men who had some labor force experience. In this sample, the respondents’ rank in the coding speed test has a 64 percent correlation with their rank in the AFQT, a composite based on the more academic tests within the ASVAB.

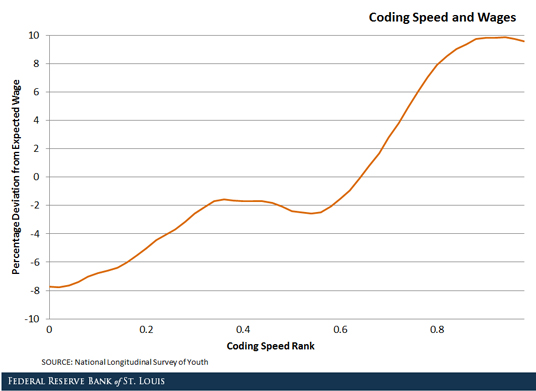

I estimated a simple regression of log wages on a bevy of traditional determinants of wages—work experience, tenure in the occupation, tenure with the employer, education level and race—and I controlled for industry and occupation. On average, someone with a coding speed score ranked 10 percentage points higher than another had a 1 percent wage advantage every year of his life. Compare this to a 10 percentage point advantage in the AFQT, which corresponds to a 3.3 percent increase. In fact, the effect is about one-quarter of the strength of a college degree.

The figure below shows the same effect, but via a semi-parametric method: The horizontal axis displays the percentage deviation from the expected wage, given all of these previously mentioned determinants except for coding speed. Quite clearly, respondents in the survey with higher ranks in coding speed made more than would otherwise be expected. Sitzfleisch has its rewards.

Notes and References

1 “50 Best Michael Jackson Songs.” Rolling Stone, June 23, 2014.

2 “Sitzfleisch.” Oxford Dictionaries. Accessed March 17, 2015.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Should Labor Productivity Be Measured?

- On the Economy: What Size Firm Has Created the Most Jobs in the Recovery?

- On the Economy: A Deeper Look at the Effect of High School Choice on Wages

Citation

David G Wiczer, ldquoWhat Sitzfleisch Has To Do with Wages,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, March 23, 2015.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions