What's a Countercyclical Capital Buffer? Here's a Rundown

You may have heard the term “capital buffer” or “countercyclical capital buffer” in the news, and are curious about what that is. A countercyclical capital buffer sounds complex, but the concept is simpler than it seems.

What Is a Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) in Banking?

Let’s break down the term, building it one word at a time.

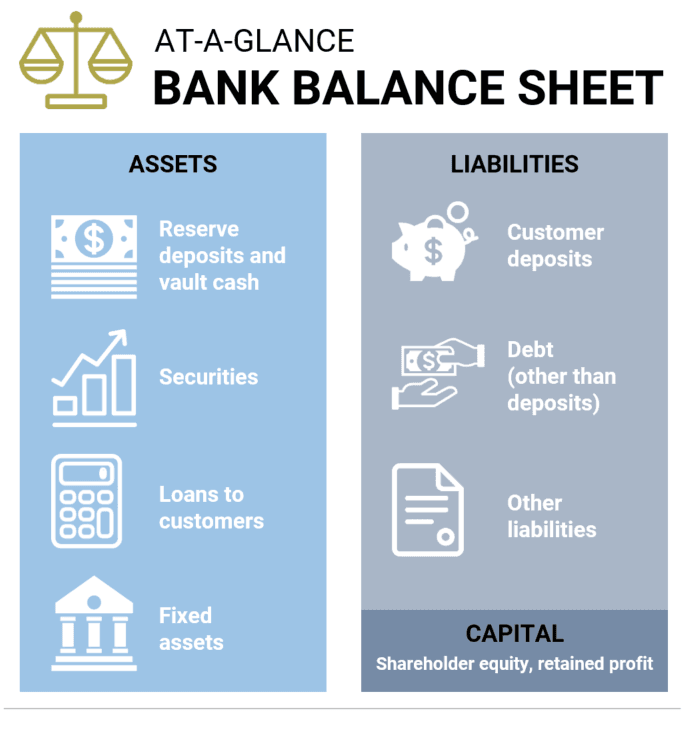

We’ll start with capital by way of a simplified explanation of a bank’s balance sheet. Generally speaking, capital is the difference between a bank’s assets, or what it owns (e.g., cash, interest-bearing loans and securities) and its liabilities, or what it owes (e.g., customer deposits).

Capital can be considered the bank’s net worth, or its equity value to shareholders. The more capital on a bank’s balance sheet, the better its ability to absorb losses. Commercial banks are subject to minimum regulatory capital requirements, taking into account the risk characteristics of assets.

A capital buffer is capital that a bank must hold in addition to the minimum requirement. One type of capital that matters for regulatory purposes is Common Equity Tier 1, which consists mostly of the bank’s common stock; Tier 1 capital is a gauge of the financial strength of a bank.

A countercyclical capital buffer is a type of capital buffer that regulators might impose on banks. The first word, “countercyclical,” adds a “when” element to the term.

A countercyclical capital buffer would raise banks’ capital requirements during economic expansions, with banks required to maintain a higher capital-to-asset ratio when the economy is performing well and loan volumes are growing rapidly. Conversely, it would require a lower capital-to-asset ratio during recessions, as the Cleveland Fed explained in a 2018 Economic Commentary article.

How Do Countercyclical Capital Buffers Work?

A buffer is often used to describe a cushion or protective barrier of some sort, aimed to reduce shock or damage. A countercyclical capital buffer is meant to do just that.

By forcing banks to hold proportionally more capital “when their assets grow rapidly (i.e., when they make a lot of loans), regulators can ensure that a larger buffer protects bank solvency should the value of those assets drop,” wrote St. Louis Fed Economist Miguel Faria e Castro in a 2019 Economic Synopses essay.

During a recession, he explained, bank assets (e.g., loans) are likely to lose value. Banks need more capital during downturns, said the Cleveland Fed, since they sustain capital losses during recessions that decrease their capital-to-asset ratios. In order to restore these ratios, banks may lend less, leading to more severe recessions and even larger capital losses.

The extra capital buffer can help ensure that banks have sufficient capital—a bigger cushion—to absorb those losses. This is a proactive attempt to protect against insolvency and possible future downturns.

What Would Be an Advantage of the Countercyclical Capital Buffer?

One possible advantage of implementing CCyBs is that they could help limit systemic risks. Many economists argue that rapid growth of credit contributed to the global financial crisis of 2007-09 and the Great Recession that followed.

Faria e Castro of the St. Louis Fed has found that use of the CCyB as a regulatory tool could have helped prevent the financial crisis and a large drop in consumption around 2007-08, though not necessarily the Great Recession that followed. He said it would have created a “soft landing” for the U.S. economy.

For banks, though, a possible bottom-line downside to the CCyB is that lending wouldn’t be as profitable during good times if they are required to hold higher levels of capital.

Who Sets the CCyB?

The Buffer Was Introduced after the Financial Crisis

The rule was first introduced in Basel III as an extension of another buffer (called the capital conservation buffer). Basel III is a voluntary set of measures agreed upon by central banks all around the world. These measures were drafted by the Bank of International Settlements’ Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in response to the financial crisis of 2007-09, in order to strengthen regulation of banks and fight risks within the financial system.

While the committee provides guidelines “to assist authorities in determining an appropriate framework,” says the BIS (PDF), rulemaking is ultimately up to individual authorities in their respective countries.

The Federal Reserve Has Not Turned on the Buffer

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve Board of Governors can consult with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the FDIC to set the CCyB. According to the Board, any buffer would apply to banking organizations subject to certain capital rules; generally, that includes those with over $250 billion in assets.

In 2016, the Board released a statement detailing the framework it would follow in setting the CCyB. It described the buffer as a “macroprudential tool that can be used to increase the resilience of the financial system by raising capital requirements on internationally active banking organizations when the risk of above-normal losses is elevated.”

As Fed Gov. Lael Brainard explained during September 2019 testimony before Congress, those risks often follow periods of rapid asset price appreciation or credit growth.

The Board votes on the capital buffer rate once a year. March 2019 was the last time it voted on it, deciding to affirm the current rate of zero. Therefore, this tool has not been used in the U.S.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has said that he views the level of capital requirements and the level of capital in the system as being “about right,” although he has acknowledged the potential usefulness of the CCyB. “The idea of putting it in place so you can cut it, that’s something some other jurisdictions have done, and it’s worth considering,” he said at a July 2019 press conference (PDF).

Meanwhile, Brainard noted in a May 2019 speech that turning on the buffer would add “an extra layer of resilience and signal restraint, helping to damp the rising vulnerability of the overall system.” She dissented from the Board’s vote last March to leave the buffer at zero.

Has the CCyB Been Used in Other Countries?

The concept of CCyBs isn’t unique to the U.S. Other countries also have them in place, including Sweden, the United Kingdom and France. Thirteen countries had announced a CCyB above zero as of March 2019, according to a speech by Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Randal Quarles. In the speech, he suggested studying how other nations have used this tool.

“Given that the CCyB is a relatively new element of our regulatory toolkit,” Quarles said, “the international experience has the potential to provide useful information on how the CCyB can be made most effective.”

Quarles voted in March 2019 to leave the CCyB rate at zero. “A notable feature of the Board's current framework is the decision to maintain a 0 percent CCyB when vulnerabilities are within their normal range,” he said in the speech, adding that the Fed’s presumption has been that the CCyB in the U.S. “would be zero most of the time.”

While future actions of the Board of Governors regarding the countercyclical capital buffer are unknown, it is likely that the subject will keep popping up in the news as economists debate the effectiveness of this relatively new tool.

Where to Find More Information:

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us