Are Parents’ Labor Participation Rates Returning to Pre-Pandemic Levels?

The child care sector was significantly impacted from the pandemic and it has yet to return to pre-pandemic employment, as my previous research has shown. Moreover, rising labor costs for child care workers, higher costs of food and baby formula shortages have placed additional strains on child care providers and families with young children during the past year.

There have been reports that the lack of affordable quality child care has kept parents out of the labor force. For example, a 2021 FEDs Notes found that caregiving reasons attributed to one-third of the decrease in the labor force participation rate (LFPR) among parents. More recently the Federal Reserve’s March 2023 Beige Book report, which is based on anecdotes, noted, “Several Districts indicated that a lack of available childcare continued to impede labor force participation.”

Labor Force Participation Rates among Parents

While it is difficult to clearly disentangle the factors that are keeping people out of work (such as limited affordable child care options, lack of transportation and health issues, among others), the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics does report annual LFPRs for men and women with children of various ages. Surprisingly, these data indicate that in 2022, the LFPR for mothers with young children have returned to or even surpassed their pre-pandemic levels.

The figures below plots the LFPR for native-born men and native-born women for three different parental groups:

- parents with children younger than 3

- parents with children younger than 6

- parents whose children are all between 6 and 17, none youngerParents with children under 3 or under 6 may also have older children in their household. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provided LFPR data by native-born and foreign-born people; for easing of viewing the figures, data for the foreign-born population were excluded. However, the results for those born abroad are qualitatively similar although the levels of overall participation are generally lower for the foreign-born population than the native-born population.

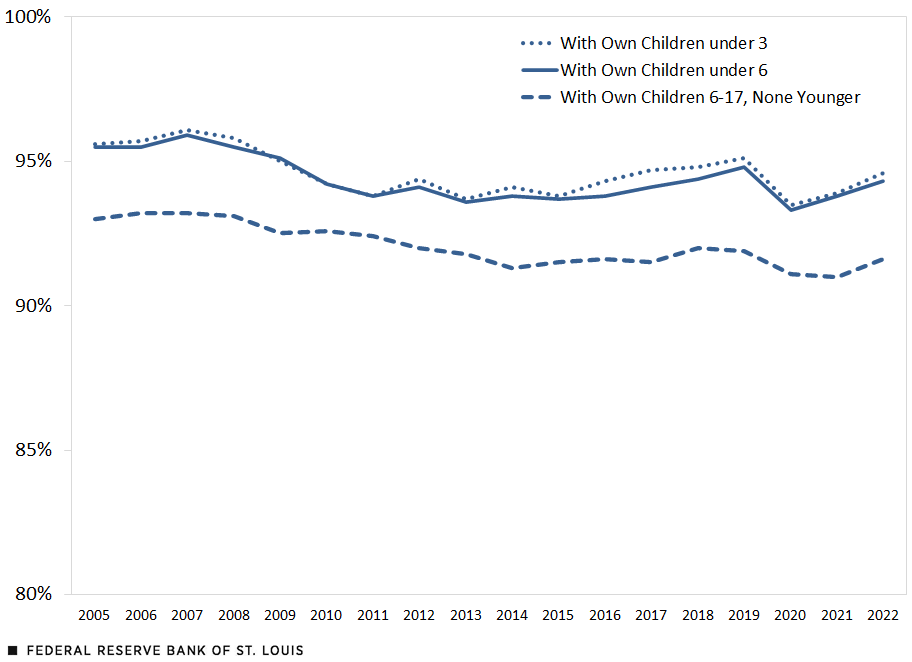

Labor Force Participation Rate, Native-Born Men

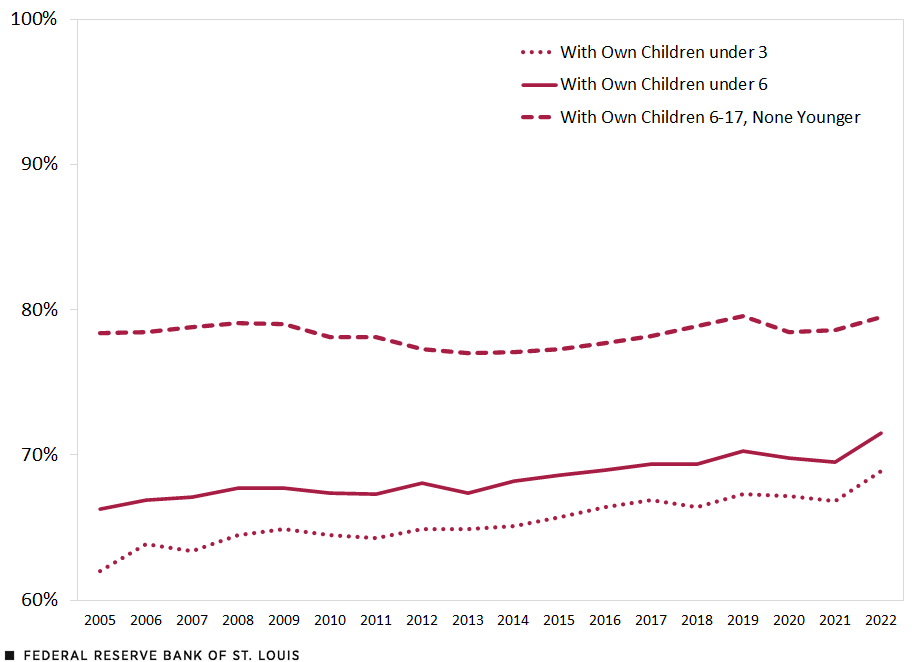

Labor Force Participation Rate, Native-Born Women

SOURCE FOR BOTH FIGURES: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The first takeaway from the figures is that the participation rate for men with children is higher than women with children. Second, notice the ordering of the lines from top to bottom for men and women is different. Men with children under 6 tend to have a higher LFPR than men with older children, whereas women with children under 6 tend to have a lower LFPR than women with older children. These first two takeaways appear to be structural attributes of the economy, not attributed to short-term fluctuations due to recessions or expansions.

The final takeaway, which also appears structural, is the upward trend for women with young children and very slight downward trend of the LFPR for men with young children. This trend has been enough to narrow the large gap between the LFPR of males and females with children under 6 by about 6 percentage points—from 29.2 percentage points to 22.8 percentage points—or about a 20% reduction since 2005.

Pandemic’s Impact on Parents’ LFPRs

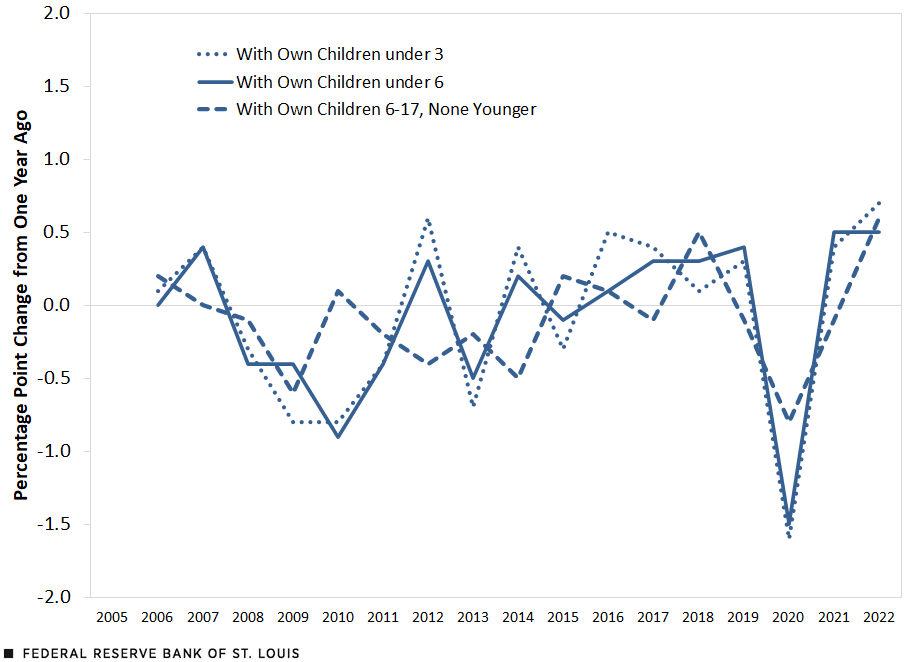

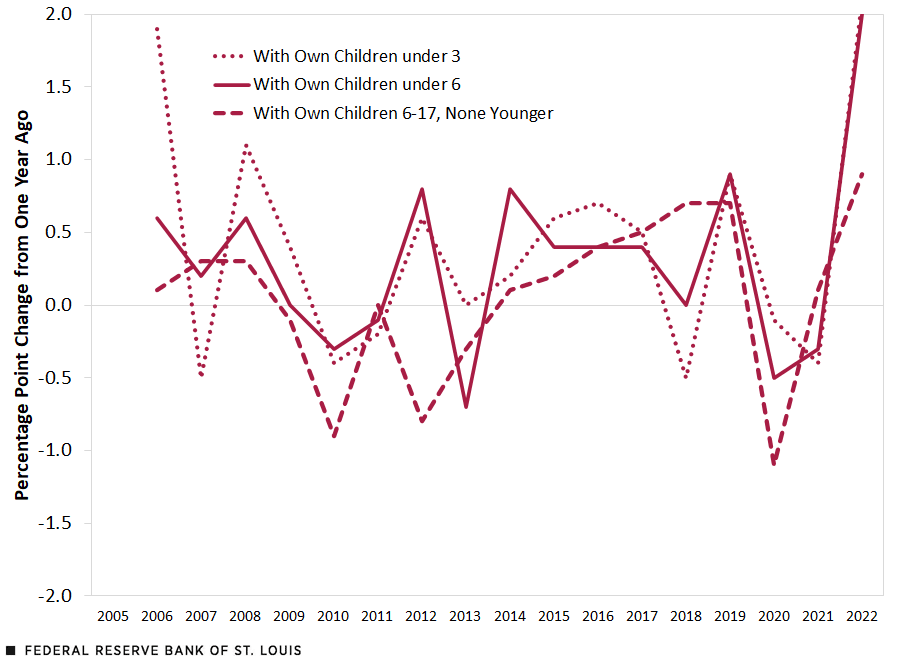

Now I’ll turn to how the pandemic affected the LFPR of parents. I plot the same data, but this time as the change from one year ago in order to account for the structural gap between men and women and more clearly depict changes. As a result, the vertical axis values on the charts below are in alignment.

Change in Labor Force Participation Rate, Native-Born Men

Change in Labor Force Participation Rate, Native-Born Women

SOURCES FOR BOTH FIGURES: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

First, note that all series declined between 2019 and 2020. This drop occurred across all age groups regardless of parental status.See the Feb. 2, 2023, FRED Blog post “Who Left the Labor Force during the Pandemic?” The LFPR of all people between ages 25-54 declined 1.1 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. Among both men and women, the steepest declines in the LFPR during the pandemic were observed among men with young children under 3 (-1.6 percentage points). For women, those with children between 6 and 17 experienced a greater decline than those with children under 6 and those with children under 3.

Lastly, the figures show recovery in the LFPR for almost all groups between 2021 and 2022. Turning back to the second figure, we see that the LFPR for women with children under 3 were about 1.6 percentage points higher than 2019 levels, though last year’s rate was almost 11 percentage points lower than the rate for those with children between 6 and 17. For men, the LFPRs have also recovered, but to a lesser extent, with the current LFPRs for the three groups about 0.5 percentage points below 2019 levels.

In summary, the data is consistent with other studies on the impact of childbirth on household work/childcare dynamics and division on labor. Among parents with young children, the LFPR for men is consistently higher than the rate for women, and although the gap has narrowed since 2005, it remains quite large. However, the data present little evidence that the continued challenges of child care—which remains costly and difficult for many to access—are keeping parents out of the workforce after 2020. Among parents with young children, only men had a lower LFPR in 2022 relative to 2019; and this result is in line with the longer-run decline in the male LFPR.

These results do not necessarily contradict analysis that finds that the lack of quality affordable childcare is a barrier to increasing the LFPR. First, a counterfactual “what-if” analysis may indicate that LFPRs of parents have the potential to be higher, including the pre-pandemic rates (as child care was a challenge before the pandemic). Second, difficulties with child care may be inhibiting parents’ ability to take on more hours, be productive at work, or accept a job with higher pay and less flexibility, which would not appear in LFPRs.

Lastly, anecdotal reports indicate that firms have adjusted work requirements to help retain workers that have caregiving responsibilities, such as allowing workers to work from home at odd hours, or not operating certain shifts, these changes by employers could effectively push up LFPRs.

Notes

- Parents with children under 3 or under 6 may also have older children in their household. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provided LFPR data by native-born and foreign-born people; for ease of viewing the figures, data for the foreign-born population were excluded. However, the results for those born abroad are qualitatively similar although the levels of overall participation are generally lower for the foreign-born population than the native-born population.

- See the Feb. 2, 2023, FRED Blog post “Who Left the Labor Force during the Pandemic?”

The Economic Impact of Child Care by State

Get child care data for all 50 states, including:

- child care affordability estimates

- data on the percentage of single parents

- labor force participation rates

- statistics about workforce-related struggles facing child care providers

Fact sheets prepared by Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis researchers.

Citation

Charles S. Gascon, ldquoAre Parents’ Labor Participation Rates Returning to Pre-Pandemic Levels?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 18, 2023.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions