Money and Inflation Explained: Feducation Video Series

[VIDEO AUDIO]

Scott Wolla: Alright, I’d like to welcome you to Feducation. This is our first go at Feducation, and if it’s a success, our plan is to make this a regular program. Today, our topic is money and inflation.

[VIDEO AUDIO FADES; VOICEOVER BEGINS]

Wolla: My name is Scott Wolla. I’m an economic education specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Feducation was developed to provide economic content and equip people with a better understanding of the Federal Reserve and its policy actions.

Our first topic was “Money and Inflation,” and we began by comparing three separate yet similar items – the front page of The Wall Street Journal, a subscription card to The Economist magazine, and a $20 bill. I asked the audience to compare these three types of paper, and then I crumpled everything together into a ball and asked for a volunteer to throw it away.

As expected, the volunteer wanted to keep the $20, and she promised to throw the rest away later. But why? What makes that type of paper – money – so special?

[VOICEOVER ENDS; VIDEO AUDIO RESUMES]

Wolla: So, we’re going to talk a little bit about functions of money to get things started.

Ok, these are characteristics that forms of money have. Money is a medium of exchange. A medium of exchange means that it makes transactions easier to conduct. So, in the absence of money, we might have to barter for goods and services. This would be a problem, maybe say for me, as an economic educator. If I wanted my transmission fixed on my car, I would have to find a mechanic who would exchange his transmission repair services for a lesson on aggregate supply and aggregate demand. In absence of a barter economy, we have this medium of exchange. So, I come to work, they pay me in cash and it’s easier to find someone who will fix my transmission for money than it is for economics lessons. So, that’s the first function of money is that money is a medium of exchange.

It’s a store of value. So, you can take the cash out of your wallet, put in your sock drawer and leave it there for three or four years. When you pull it out again, it’s got the same value, minus inflation, as when you put it I, unlike bushels of corn. In a commodity or barter-based economy, you might take a few bushels of corn and stick them in the corner of your shed, and then the chickens might eat it, or it might rot. But money is actually a very good store of value.

It’s a measure of value. So, I was talking to one of my friends on the phone this weekend, and I was saying how happy I was that the gas prices were down. I quoted the price; it was $3.29 on Friday, and he said “well here, it’s $3.04,” and I was not quite as excited as I once was about cheap gas prices. But, we were both quoting prices as a measure of value. I didn’t quote the price of gas in terms of corn and then he comes back and price it in terms of chickens. We both quoted the price in terms of money, and that makes those transactions easier as well.

[VIDEO AUDIO ENDS; VOICEOVER RESUMES]

Wolla: To further our discussion of money, I introduced a guest auctioneer, and we conducted an auction. Each audience member was given a certain amount of plastic chips, and each chip was worth $1. Our first round consisted of three separate lots for auction items, which represented the total output of our auction economy. These items included a voodoo doll keychain, two chocolate bars and a gift card, and a FRED® hoodie from the St. Louis Fed.

The bidding was fast and furious, and at the end of the first round, we tallied up the winning bids. Then we handed out more chips and held a second auction for an identical group of items. Once again, bidding was fast paced, and again we tallied the winning bids at the end of the auction.

[VOICEOVER ENDS; VIDEO AUDIO RESUMES]

Wolla: So, this is how things turned out: in our first round, the total price paid for all three goods was $30; in round two it was $103. Now, were there any differences in the goods that were sold in the two rounds? No, because they were identical, weren’t they? So, how would you explain the difference in the price? In round two, more than three times the total price was [paid for the three goods.] It was the quantity of chips, right? And the chips in this auction represented… money. Alright, so would it be safe to at least make an early conclusion that the amount of money had something to do with the price of the goods in the two auctions or markets? Ok, so we’ll go with that. So, our prices were higher, presumably because there was more money in the second round than the first round.

All right. So, we’re going to talk about inflation today, which we’ll define as a sustained increase in the average price level of all goods and services produced in the economy. There are a couple key terms. One of them is “average price level.” So, for instance, when the price of gas goes up and down, or the price of milk goes up and down, it doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s inflation, because inflation is a basket – it’s the average price level. So, instead of looking at the prices of individual goods, when we look at inflation, we look at the price level of that entire basket of goods that are in the measure. So what causes inflation?

[VIDEO AUDIO ENDS; VOICEOVER RESUMES]

Wolla: Inflation is caused when the money supply in an economy grows at a faster rate than an economy’s ability to produce goods and services. In our auction economy, the production of goods and services was unchanged, but the money supply grew from round one to round two. Because the money supply grew, and the output of goods and services did not grow, our economy experienced inflation.

I needed volunteers for the next part of the program and recruited five willing audience members. The volunteers were each given a sign displaying one of five symbols, which formed the equation of exchange.

[VOICEOVER ENDS; VIDEO AUDIO RESUMES]

Wolla: So, let’s define our variables. M we’re going to define as the money supply in the economy. We’re going to think about coins. We’re going to think about currency. We’re going to think about deposits and checking accounts, traveler’s checks, and anything that you spend as money.

V is velocity. When you think velocity, you think speed. In this case, velocity is the number of times per year that the average dollar is spent on goods and services. So you have the amount of money and then the number of times that it’s spent in a time period, in this case, a year.

Our equal sign is just kind of our placeholder there.

P is the overall price level – not the prices of individual goods – this is the price level of that basket of goods, all the output sold in the economy.

And Q is the quantity of goods and services produced, also known as output.

[VIDEO AUDIO ENDS; VOICEOVER RESUMES]

The equation of exchange is a simple model of a macroeconomy during a time period. MV represents the total amount spent by buyers, and PQ represents the total amount received by sellers. Because this is an equation, one side must equal the other. If there’s a change of the variables in one side of the equation, then this must be reflected by a change on the other side of the equation in order to keep MV equal to PQ. I asked M to raise her letter and Q and V to remain steady. In this example, what happens to P? P must increase in order to keep both sides of the equation equal.

In other words, when the money supply increases and neither velocity nor quantity changes, the price level must also increase. We call this inflation. This equation helps us understand the relationship between money supply and price level. The opposite holds true as well. If M decreases and we hold V and Q constant, then P must decrease. Think about a recession. During a recessionary period, V might decrease as people cut spending. Remember, V is the velocity of money or the number of times a year that the average dollar is spent on final goods and services. So, if we see a decrease in V while M and Q remain constant, we can expect to see a decrease in P as well.

On the other hand, during an inflationary period, V might increase as people rush to make purchases before prices rise too much – so the money supply might turn over faster – and keeping M and Q constant, P might increase as well, leading to even higher prices and further inflation.

The equation of exchange is most often used to describe what will happen over the long run, but it has both long and short run considerations, and this is where it may be more applicable to Fed policy. Assuming that resources are underutilized in a recession – this means there is high unemployment, and that factories and equipment are sitting idle – we would expect to see a decrease in Q, the quantity of all goods and services produced in the economy. Under these conditions, how would the variables respond to an increase in M, the money supply?

In an economy where resources are underutilized, Q might start to rise a response to an increase in M. Seems simple, right? But what if M stayed high for an extended period? How would these other variables respond? Eventually, P would start to rise as well and that’s where we get the “short run, long run” story of inflation. During periods of underutilization, when the money supply is increased, there will be an increase in output. However, as those idle resources are utilized – idol factories return to production and the labor market begins to tighten up – an increase in the money supply will be reflected in the price level. This is inflation caused by too much money chasing too few goods.

The equation of exchange can be useful in terms of macroeconomic application. It provides a framework for understanding the economy, and it tells about the importance of the money supply. M can be used to influence P and Q. In the short run, it can have some effect on Q, but in the long run, it’s all about P. It’s all about the price level.

The Federal Reserve is the central banking system in the United States and, among other things, the Fed has the job of conducting monetary policy to influence the growth of the money supply. Monetary policy is when a nation’s central bank uses its monetary policy tools to achieve such goals as maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates. The Federal Reserve’s dual mandate is to promote the two co-equal objectives of maximum employment and price stability.

When people think about the Federal Reserve, they often think about the monetary policy piece. They see Chairman Bernanke testifying in front of Congress, or hear about what the FOMC did, but the link between the money supply and the other variables is not always well understood.

To summarize, the money supply is important because if the money supply grows at a faster rate than the economy’s ability to produce goods and services, inflation will result. Also, a money supply that does not grow fast enough can lead to decreases in production, leading to increases in unemployment.

This video was produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. For more information, visit us online at stlouisfed.org.

Money, as a concept, is largely dependent on the functions it serves in any given economy, but how is the value of money itself determined? In this video, review the functions of money, the relationship between the supply of money and inflation, and how changes in the money supply affect the economy.

More Feducation Videos

Unemployment and Monetary Policy

Discover how unemployment is defined and measured in economic terms, and how the Fed pursues maximum employment and price stability.

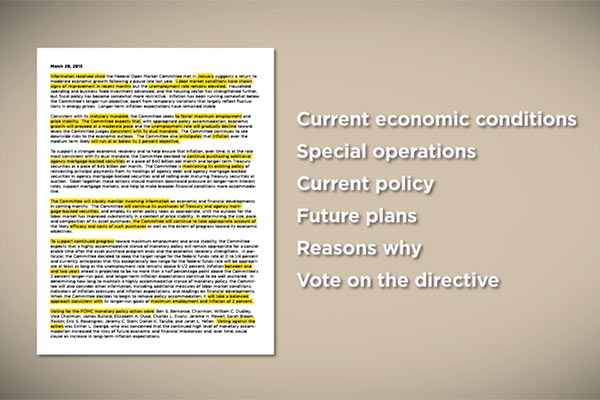

Understanding an FOMC Statement

Learn how to read and understand an FOMC statement and what the statements mean. This video overviews Fed communication strategies for transparency and clarity.

---

If you have difficulty accessing this content due to a disability, please contact us at economiceducation@stls.frb.org or call the St. Louis Fed at 314-444-8444 and ask for Economic Education.