Economic Forecasting: Comparing the Fed with the Private Sector

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Fed needs to forecast the U.S. economy to properly conduct monetary policy. Evidence suggests the Fed has generally been more accurate than private forecasters.

- Economists offer several reasons why the Fed may have an advantage, including more timely access to economic data and knowledge about the path of future monetary policy.

- Evidence also suggests an erosion of the Federal Reserve’s forecasting advantage.

Before the Federal Reserve can properly conduct monetary policy, it must first evaluate the state of the economy. To that end, the Fed expends considerable resources in generating forecasts of macroeconomic variables, including the growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP), the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. Many of these forecasts are contained in the Greenbook (now called the TealbookPrior to June 2010, the staff at the Board of Governors produced both the Greenbook and the Bluebook in preparation for FOMC meetings. In June 2010, the staff at the Board of Governors merged the content to form the Tealbook.), which is distributed to members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) a few days prior to the meetings at which they set monetary policy.

Academics seem to have spent nearly as many resources studying the Fed forecasts as the Fed has spent creating them. One robust finding is that the Fed forecasts have been, on average, more accurate than many private sector forecasts.Accuracy is often measured by computing the average of the squared forecast error (the difference between the forecast and the realization) over a period of time. A lower value of the average of the squared forecast error indicates a higher level of accuracy.

Why might the Fed have an advantage over the private sector forecasters? Three reasons are often cited:

- The Fed simply devotes more resources to forecasting or has better forecasters.

- The Fed has access to more timely information.

- The Fed knows about the path of future monetary policy, but the private sector does not.

Federal Reserve and Private Sector Forecasts

The Federal Reserve produces a number of different forecasts. One example is the Summary of Economic Projections, an anonymized survey of the Fed’s reserve bank presidents and the board governors, which is commonly discussed in the media covering monetary policy.

The Greenbook forecasts, on the other hand, are produced by the Board of Governors staff. To construct the Greenbook forecasts, the board staff uses both econometric models and subjective assessments. Moreover, the Greenbook forecasts are constructed using a “suggested path” for monetary policy. (Economists call forecasts constructed in this manner "conditional" or "scenario" forecasts). These forecasts do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any single member of the FOMC nor the FOMC as a whole, as they are calculated before the committee makes a decision on policy.

The Greenbook forecasts are made publicly available five years after the FOMC meeting for which they were constructed.The Greenbook forecasts that are publicly available can be found at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia's website. Prior to the 1980s, the Greenbook forecasts were available monthly; after 1981, the Greenbook was produced only for FOMC meetings, which have changed their timing and frequency over the years. (Currently, the FOMC meets eight times a year.)

While the Greenbook includes a number of forecasts, academic research has typically concentrated on these three series:

- Output growth—GDP or gross national product (GNP) growth, depending on when the forecasts were made

- Inflation—The rate of change of the GNP or GDP deflator, the consumer price index (CPI) or the personal consumption expenditures price index, depending on when the forecasts were made

- Unemployment rate

Private sector forecasts are constructed by banks, firms and private forecasting consultants. One private sector forecast that many academic studies use is the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) consensus forecast, which is constructed from a number of individual private sector forecasts.

In the late 1960s, the National Bureau of Economic Research and the American Statistical Association began collecting the individual forecasts that make up the SPF. The SPF was taken over by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in 1990, at which point the collection of forecasts became publicly available.The Survey of Professional Forecasters is available on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia's website. The survey is quarterly, meaning that the private sector forecasts do not always correspond in timing to the Greenbook forecasts produced by the Fed. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia aggregates the individual forecasts to form a consensus forecast, which is often taken to be a market representative forecast.

Are Fed Forecasts Better than Private Sector Forecasts?

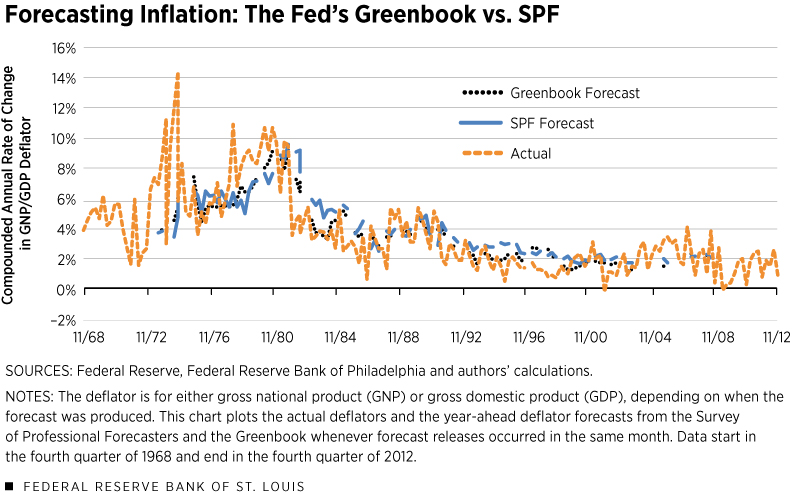

Given the volume of resources that the Fed devotes to forecasting, it is perhaps not surprising that academic studies have found Greenbook forecasts to dominate many private sector forecasts, including the consensus SPF forecast. In their 2000 study, economists Christina and David Romer compared the Greenbook’s forecasts for the compounded annual rate of change in the GNP deflator, which is one measure of inflation, with the SPF consensus forecast for the period 1968 to 1991. (In 1991, the Greenbook switched from forecasting the GNP deflator to forecasting the GDP deflator.) The Romers found that the Fed, generally, was more accurate forecasting inflation than the private sector.

The accompanying figure plots the one-year-ahead Greenbook forecasts for the change in the deflator for GNP and then GDP, the one-year-ahead SPF forecasts for the change in the GNP/GDP deflator, and the released value (third release) for the change in the GNP/GDP deflator over the period starting in the fourth quarter of 1968 and ending in the fourth quarter of 2012.Both the Greenbook and the SPF changed their measure of the deflator forecasts two times during the sample period. In the start of the sample (1968-1991), the deflator is measured as the price index for GNP; from 1992 through 1995, it is the price index for GDP, and from 1996 onward it's the chain-weighted GDP price index.

Using only observations when there were Greenbook and SPF forecasts in the same month, we calculated that the Fed's forecasts are more accurate than the SPF's, with the mean squared error of the Greenbook forecast being 3.40 compared with 4.77 for the SPF forecast. The Romers’ result extended to forecasts of output growth, but the results were neither as stark nor as robust.

Why Does the Fed Have a Forecasting Advantage?

There are a number of reasons why the Fed might have a forecasting advantage over the private sector. One reason—and the reason advanced by the Romers—is that the Fed simply devotes more time and resources to forecasting than does the private sector. While this might be reasonable on its face, it does not explain more recent findings that the Fed’s forecasting advantage has appeared to decline over the years.See Gamber and Smith.

A second reason is that the Fed has access to data in a more timely fashion than does the private sector. For example, the FOMC has access to the current value of industrial production before it is released to the public because the Fed constructs it. This informational advantage, however, lasts only a few days and is often dissipated by the time the private sector forecasts are collected. This explanation is discounted by studies, such as the one by the Romers, that argue that accounting for the possible discrepancy in the information set does not alter the Fed's apparent informational advantage.

A third reason stems from the fact that the Fed forecasts are made conditional on a path for future policy. If the Fed knows the monetary policy but the private sector does not, the Fed would have an informational advantage. This explanation could also account for the erosion of the Fed's advantage: The Fed has taken steps to increase transparency in recent years, thus giving the private sector more information about the likely path for policy. The Romers discounted this explanation, though, arguing that the Fed's apparent informational advantage shows up in short-term forecasts. Given that monetary policy is generally thought to be only effective at long and variable lags, the Romers argued that the Fed’s forecasting advantage at short horizons suggests that knowing the path of policy is not the source.

After the Romers’ article, studies published by economists Edward N. Gamber and Julie K. Smith as well as Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco economist Pascal Paul suggest that the Fed's forecasting advantage has eroded. Are any of these hypotheses consistent with a decline in the Fed's forecasting advantage? If the Fed's forecasting advantage is due to its knowledge of the future path of monetary policy, the Fed's increased communication and transparency that began in 1994 may have contributed to the private sector "catching up" with the Fed.

Gamber and Smith also argued that the nature of forecasting has changed over time. Since 1984, the volatility of many U.S. macroeconomic variables, including GDP and inflation, has declined. During the same period, economists have found that it has become harder to beat even the simplest forecasting models.For example, a univariate autoregressive forecast (a forecast built using only lags of the variable being forecasted) is hard to beat when it comes to forecasting inflation post-1984. In this sense, if the Fed's forecasting advantage stemmed from its devotion of more resources to forecasting than the private sector, but sophisticated models are no longer advantageous, one would suspect the Fed's advantage to decline.

Julie K. Bennett, a research associate at the Bank, provided research assistance.

Endnotes

- Prior to June 2010, the staff at the Board of Governors produced both the Greenbook and the Bluebook in preparation for FOMC meetings. In June 2010, the staff at the Board of Governors merged the content to form the Tealbook.

- Accuracy is often measured by computing the average of the squared forecast error (the difference between the forecast and the realization) over a period of time. A lower value of the average of the squared forecast error indicates a higher level of accuracy.

- The Greenbook forecasts that are publicly available can be found on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s website.

- The Survey of Professional Forecasters is available on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s website.

- Both the Greenbook and the SPF changed their measure of the deflator forecasts two times during the sample period. In the start of the sample (1968-1991), the deflator was measured as the price index for GNP; from 1992 through 1995, it was the price index for GDP; and from 1996 onward it’s the chain-weighted GDP price index.

- See Gamber and Smith.

- For example, a univariate autoregressive forecast (a forecast built using only lags of the variable being forecasted) is hard to beat when it comes to forecasting inflation post-1984.

References

Gamber, Edward N.; and Smith, Julie K. “Are the Fed’s Inflation Forecasts Still Superior to the Private Sector’s?” Journal of Macroeconomics, June 2009, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 240-51.

Paul, Pascal. "Does the Fed Know More about the Economy?" Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2019-11, April 8, 2019.

Romer, Christina D.; and Romer, David H. “Federal Reserve Information and the Behavior of Interest Rates.” American Economic Review, June 2000, Vol. 90, No. 3, pp. 429-57.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us