Why Do Gasoline Prices React to Things That Have Not Happened?

Have you ever wondered why gasoline stations raise their prices in response to fears about future supplies of oil? You may have thought to yourself, "I know the gasoline in the station's underground storage tank was purchased before the world price increased. How can they raise the gas price now? The gasoline market must be rigged."

In fact, gasoline stations should raise their prices to reflect increased future costs of replacing their inventories. Prices act like engine or voltage regulators—they automatically speed up or slow down the flow of the commodity in order to maximize performance, or what economists call allocative efficiency.1

Oil and Gas, Here and There, Then and Now

To understand why U.S. gas prices respond now to things that might happen in the future, halfway around the world, one must understand how spot and futures prices for storable commodities, such as oil or gasoline, are related to each other.

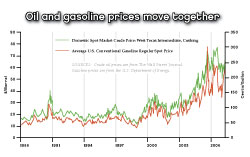

The cost of oil comprises about half the cost of gasoline, but oil is the most volatile component; other factors, such as taxes and profit margins, do not change often.2 The figure shows that while gasoline prices can diverge from oil prices for short periods because of seasonal demand, tax changes or other reasons, the two prices are closely linked over longer periods.3

Because oil can be transported anywhere, trading on global spot and futures markets determines the global price of a given grade of oil, aside from local taxes and transportation costs.4 Oil can either be sold for immediate delivery or stored for sale in the future; so, firms adjust their inventories in response to news about the future supply and/or demand for oil. For example, an unsuccessful terrorist attack on a Saudi Arabian oil facility might create fears of further incidents that would actually disrupt supplies from the Persian Gulf. These fears would raise expected future prices and current spot prices, too. Current prices rise because the rise in the futures price will encourage firms to take oil off the spot market and sell it for delivery in the future. This inventory increase keeps the spot and futures prices moving up together.

Because oil is such an important component of gasoline, wholesale gasoline prices react instantly to changes in oil prices, including those caused by expectations of future events. The price at your local gas station will change nearly as quickly as the wholesale price.

The close connection between world oil prices and local gasoline prices can be seen by considering how two hypothetical competing gasoline stations in a small town would react to a sudden increase in the price of oil. On one quiet morning, both the Conch Gas station and the Pegasus Gas station were charging $1.999 per gallon of regular gasoline. They each had bought their inventories a few days before at a cost of $1.48 per gallon. With federal, state and local taxes combining for 50 cents per gallon, each station calculated that it would make about 2 cents per gallon at a retail price of $1.999.5

During the late morning, news of an unsuccessful terrorist attack on Saudi Arabian oil fields spurred widespread fears of cuts in future oil supplies. As frenzied trading on exchanges in New York, London and elsewhere bid up the world price of oil, the owner-manager of the Conch Gas station learned that wholesale gasoline prices for delivery next week had increased by $1 per gallon. "Folks aren't going to like this," she muttered to herself as she adjusted the prices on her gasoline pumps and climbed the ladder to raise her posted price to $2.999 per gallon. The owner-manager of the Pegasus Gas station had just finished changing his price to $2.999 when the two managers shrugged and nodded to each other across the street before they walked back into their respective stations.

Despite much grumbling at the price increases, sales at the Conch Gas and the Pegasus Gas stations proceeded much as before—both stations sold out their existing inventories right on schedule and then took delivery on a new load of gasoline at the new, higher wholesale prices. The station owners made a tidy, unexpected profit that week—$1.02 per gallon.

Are the Gas Stations Gouging Us?

Did the stations' simultaneous price changes the week before wholesale prices actually went up prove that Conch Gas and Pegasus Gas were colluding to gouge consumers? No. These competing station owners did not have much choice if they wanted to remain as profitable as their competitors and stay in business over the long haul. Let's consider why they raised their prices in response to announcements of wholesale price increases and what would have happened if they had not done so.

Suppose first that only Conch Gas had held its price at $1.999, while Pegasus Gas had raised its price to $2.999. Conch Gas obviously would have captured all of the traffic that day, but its storage tank would have run dry much sooner than expected. By the first or second day after the overseas disruption in the oil market, the owner-manager of Conch Gas might as well have gone on vacation—although she would have been better off if she worked throughout the week and charged the higher price. Meanwhile, the manager of Pegasus Gas—who took his vacation in the first two days of the crisis—returned to sell out his remaining inventory at $2.999 per gallon. In the end, the Pegasus Gas station made a much larger profit. The manager of Conch Gas will not make this pricing mistake again.

Now suppose that both Conch Gas and Pegasus Gas had decided to show home-town solidarity by keeping their prices at $1.999, at least until the new, higher-cost gasoline inventories arrived in a few days. Local residents certainly would have been appreciative, but so would all of the eager drivers from neighboring towns who would have driven in to enjoy "cheap" gas. In this case, consumers would have had to line up for gas, and both the Conch and Pegasus stations would have run dry before their replacement inventories arrived. Anyone in this town who was unfortunate enough to need gas on the third day of the crisis would have been out of luck. Taking the entire region into account, it is likely that about the same amount of gasoline would have been sold during the first days after the crisis as otherwise would have been the case. But there would have been wasteful driving by out-of-towners seeking cheap gas, while local residents would have been inconvenienced by the gas lines and the shortage when the Conch and Pegasus stations ran dry.

Consider one final possibility: What if all the gasoline stations in the state had agreed to keep their prices at $1.999 until higher-cost supplies started arriving? Even if the flow of out-of-state bargain hunters turned out to be small, a state-wide shortage of gasoline would have been almost guaranteed in short order. How could this happen? Recognizing that gas prices were only temporarily low and were bound to rise soon, all rational owners of cars, trucks, tractors, off-road vehicles, lawn mowers or leaf blowers would fill up their tanks as quickly as possible. That is, any attempt to constrain the retail price of gasoline in the face of higher future prices simply induces a scramble among buyers to beat the price increase. Many people would make wasteful extra trips to top off half-full tanks, and others would be genuinely inconvenienced as shortages developed.

Thus, the simultaneous price increases by Conch and Pegasus Gas are not harmful price gouging at all. Although no one likes to pay more for gas, market-determined gasoline prices operate to prevent shortages and maximize economic efficiency.

Endnotes

- Allocative efficiency means that consumers get the goods for which they are willing and able to pay. [back to text]

- See Energy Information Administration. [back to text]

- Although the figure shows just one grade of oil, West Texas Intermediate, the prices of all grades of oil tend to move closely together. [back to text]

- A spot market is one in which commodities are traded for near-term delivery—within a month for oil markets (Haubrich et al.). A futures market is one in which a commodity is traded for delivery on a specified future date, which could be months or years away. Major fuel users, such as airlines and trucking companies, often buy oil in futures markets to guarantee the cost of the fuel they will use. Oil suppliers are more likely to sell oil contracts in futures markets. [back to text]

- Other components of gasoline prices include taxes and the retail markup. The federal tax on gasoline is 18.4 cents per gallon; state and local taxes vary from 8 to 50 cents per gallon. The local service station makes about 1-4 cents of profit per gallon. See National Association of Convenience Stores. [back to text]

References

Energy Information Administration. "A Primer on Gasoline Prices." U.S. Department of Energy, May 2006. See www.eia.doe.gov/bookshelf/brochures/gasolinepricesprimer/printerversion.pdf.

Haubrich, Joseph G.; Higgins, Patrick; and Miller, Janet. "Oil Prices: Backward to the Future?" Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Commentary, December 2004. See http://clevelandfed.org/Research/Commentary/2004/Decnew.pdf.

National Association of Convenience Stores. "Retailer Margins Shrink as Prices Climb." Industry Resources, May 2007.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us