Labor Force Composition during the COVID-19 Pandemic

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Compared with the U.S., the Eighth Federal Reserve District’s labor market experienced a slightly milder downturn in 2020-21.

- In the District, Black workers, workers of other races, high school dropouts and older workers were more likely to be out of the labor force.

- The District’s sectors with relatively more unemployed workers were manufacturing, transportation, and administrative and support services.

Examining the ins and outs of the labor force is essential for understanding the dynamics of the labor market, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. This article focuses on two dimensions of the labor force, both in the Eighth District and nationally. The first is the demographic makeup of who is in the labor force (i.e., employed or unemployed people) versus out of the labor force. The second is the industrial composition of employment and unemployment.

We found that, compared with the U.S. as a whole, the Eighth District experienced a slightly milder downturn in 2020-21. Although the pool of individuals who left the labor force in the Eighth District looks similar to that of the nation, the recovery of employment in the hardest-hit industries has evolved faster in the Eighth District.

What Labor Force Participation Reveals

We began by analyzing labor force participation. An individual is considered out of the labor force, or a nonparticipant, if he or she is not currently searching for work. Although workers who are out of the labor force do not contribute to the unemployment rate, they do contribute to the shortfall in the number of jobs that the U.S. has seen since the start of 2020.As of August 2021, employment remained 5.3 million below its value in February 2020.

We used microdata from the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is a source for the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ official employment reports. In this survey, respondents can be tracked from month to month (in four-month blocks), which means we can record changes in labor force status.

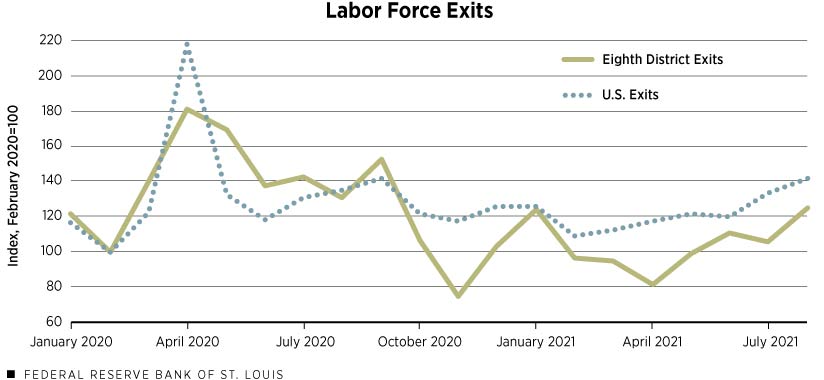

In the first figure, we report the number of workers who exited the labor force in each month for the entire U.S. and the Eighth District.Because of the high incidence of missing values in the CPS’ county variable, we classified a respondent as being a resident of the Eighth District if he or she reported living in one of its metropolitan statistical areas; people living outside of the District MSAs were excluded from this study. In all cases, the series is normalized to 100 in February 2020, immediately before the pandemic impacted the economy.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

The figure shows that, relative to pre-pandemic levels, labor force exits increased over the rest of 2020, with the largest spike early on. Compared with the U.S. as a whole, the Eighth District had a lower incidence of exiters initially, but they have since followed a similar path.

Labor force exits are now slightly lower in the Eighth District. Note that these exits are not necessarily permanent, but once somebody exits, their probability of being reemployed in the future decreases relative to someone who remains unemployed but is still actively searching for a job. Therefore, the pattern of exits is relevant to how quickly the recovery unfolds.

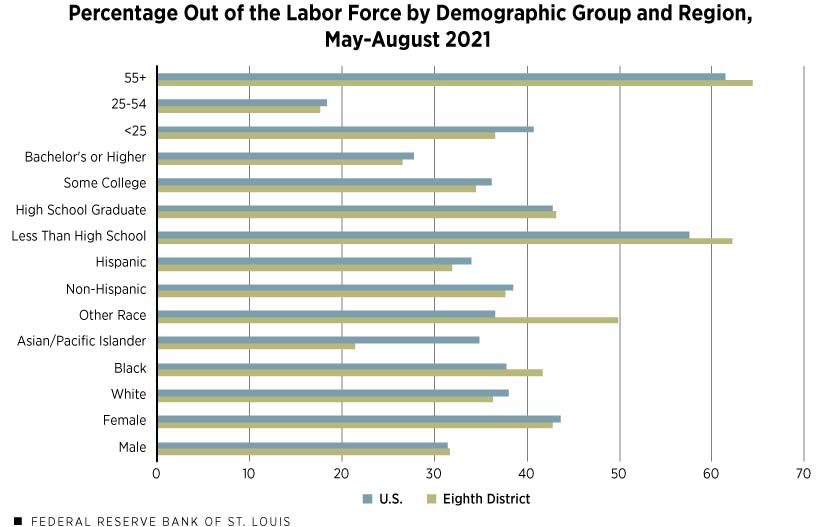

Next, we examined who remained out of the labor force from May to August 2021. Specifically, we looked at how an individual’s demographic characteristics relate to whether they are in or out of the labor force. The second figure shows the probability that a member of each demographic group was out of the labor force.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

The general trends are similar in the U.S. as a whole and in the Eighth District. Women, less-educated workers and non-prime-age workers are most likely to be out of the labor force. These facts are robust and have generally held true over the past several decades, regardless of the state of the business cycle.

The likelihood of being out of the labor force is similar for individuals inside and outside the Eighth District, with the exception of a few groups: Blacks, other race, high school dropouts and workers older than 55 are slightly more likely to be out of the labor force in the Eighth District; Asians and Pacific Islanders, as well as workers younger than 25, are more likely to be in the labor force in the Eighth District.Note that there is overlap between the different bars in this chart. For example, if a certain gender, education or racial group is disproportionately composed of prime-age workers, the bar will exhibit a lower probability of those workers being out of the labor force.

Industry-Specific Statistics during COVID-19

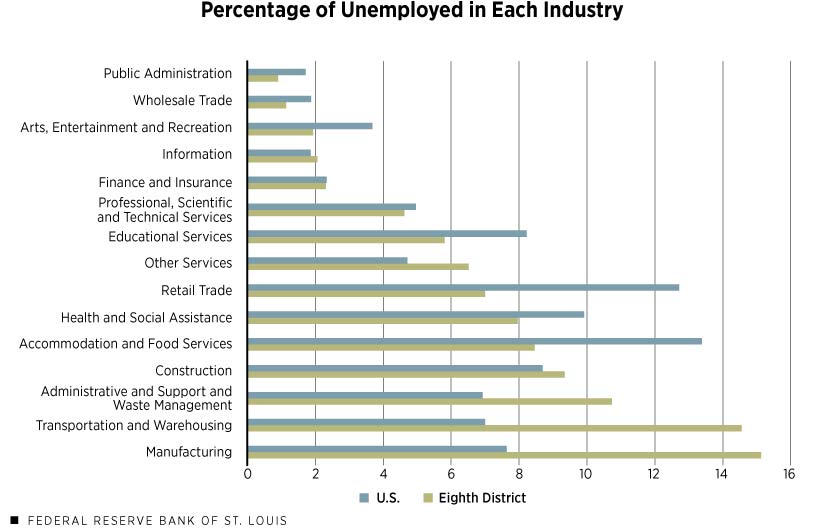

Next, we analyzed how different industries have been impacted by the pandemic. The CPS microdata enabled us to observe the most recent industries for respondents who reported being unemployed. Using these responses, we calculated the percentage of unemployed workers who were previously in each industry.

The results are shown in the third figure below. The industry composition of the unemployed partly reflects the number of jobs in each industry: For example, nationwide, there were many unemployed health care workers because there are a lot of health care jobs. Relative to the rest of the U.S., the Eighth District had more unemployed workers in manufacturing; transportation and warehousing; administrative and support and waste management services. It had fewer unemployed workers in accommodation and food services; health care and social assistance; retail trade; and educational services.

How quickly these workers get reabsorbed into jobs will depend on several factors: demand for each industry’s output, the bounce-back from pandemic-related shutdowns and wages offered. Note also that the facts reported in the third figure do not account for new labor market entrants (who, by definition, do not have a previous industry of employment) and may not be indicative of the industries in which these workers are truly focusing their job search efforts.

SOURCES: Current Population Survey and authors’ calculations.

We can get some sense of how quickly each industry is recovering by looking at the evolution of employment for different industries during the pandemic. This gives a more complete picture of what has been happening across time. These changes in employment also reflect people who have left the labor force and do not appear in the unemployment pool. These data come from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), which aggregates employer-related counts of employment and wages.However, employment is reported monthly in the QCEW.

| Industry and Region | April 2020 | March 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| All Industries | ||

| Eighth District | -13 | -3 |

| U.S. | -16 | -5 |

| Retail Trade | ||

| Eighth District | -14 | -1 |

| U.S. | -16 | -2 |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | ||

| Eighth District | -10 | -3 |

| U.S. | -11 | -4 |

| Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | ||

| Eighth District | -55 | -21 |

| U.S. | -49 | -27 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | ||

| Eighth District | -39 | -9 |

| U.S. | -46 | -19 |

| Other Services, Except Public Administration | ||

| Eighth District | -23 | -7 |

| U.S. | -30 | -11 |

| SOURCES: Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages and authors’ calculations. | ||

The results for overall employment, as well as a few select industries, are shown in the table. Each column shows the percentage drop in employment relative to February 2020. The table shows that in the U.S. as a whole, employment had fallen to 84% of its pre-pandemic level by April 2020—a 16% decline. The decline was similar but slightly milder in the Eighth District, which saw only a 13% decline. Since then, both have been recovering at similar paces, but the Eighth District remains slightly ahead of the U.S. as a whole, with 3% lower employment compared with 5% nationwide.

Disaggregating these numbers by industry helps in understanding where the shortfalls remain and why the Eighth District looks different from the U.S. Retail, which is a large industry that contains a mix of essential and nonessential services, evolved similarly to aggregate employment. Health care, another sector at the forefront of the pandemic, saw smaller initial declines and has since rebounded similarly nationwide and in the Eighth District. Both industries have nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The largest declines in employment and the greatest differences between the Eighth District and the rest of the country lie in the following industries: arts, entertainment and recreation; accommodation and food services; and other services (which include repair services and personal services, such as salons and dry cleaning).

These industries were generally hit less hard in the Eighth District compared with elsewhere. An interesting case is the arts, entertainment and recreation industry: In the Eighth District, it had a larger initial decline but now remains closer to pre-pandemic levels than in the U.S. as a whole. These harder-hit industries are where the gaps between the U.S. and the Eighth District remain largest today.

Conclusion

We found that the demographic characteristics of those who have left the labor force are similar in the Eighth District and elsewhere. However, the Eighth District experienced a milder downturn compared with the rest of the country. This was driven by different responses in the Eighth District for the sectors of the economy most affected by the pandemic.

These differences may be related to less-restrictive economic policies put in place to battle the pandemic, rather than the course of the virus itself. It is also important to keep in mind that the features of labor force composition examined here are just one dimension of how the Eighth District has fared; just a few others include differences in health outcomes, wages and business closures.

Endnotes

- As of August 2021, employment remained 5.3 million below its value in February 2020.

- Because of the high incidence of missing values in the CPS’ county variable, we classified a respondent as being a resident of the Eighth District if he or she reported living in one of its metropolitan statistical areas; people living outside of the District MSAs were excluded from this study.

- Note that there is overlap between the different bars in this chart. For example, if a certain gender, education or racial group is disproportionately composed of prime-age workers, the bar will exhibit a lower probability of those workers being out of the labor force.

- However, employment is reported monthly in the QCEW.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us