The Fintech Revolution in Banking

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The rise of financial technology—fintech—has heightened rivalry in an already competitive banking industry.

- Traditional financial institutions such as commercial banks, thrifts and credit unions have responded by expanding their digital footprints.

- How much and how fast consumers continue adapting to fintech will shape the banking industry for years to come.

Today, the provision of banking services is more competitive than ever, and financial technology (fintech) has turbocharged this trend. Fintech refers to the software and applications that facilitate financial transactions on computers, tablets and smartphones.

Fintech is used by traditional financial institutions—commercial banks, thrifts and credit unions—to provide some services. But these institutions face stiff competition by nonbank fintech firms. Some fintech companies specialize in one product or service or target a very narrow customer base, while others offer a wide array of products to a range of customers.Venmo and PayPal are two well-known fintech firms that use fintech to facilitate person-to-person payments. LendingTree, a leading provider of home loans, is another example of a fintech firm. See this brief primer on fintech. Several have sought to become more like banks, either obtaining bank or bank-like charters.

Traditional financial institutions are not standing still. Technological innovations like online and mobile banking have become mainstream, and some banks are increasing their digital footprint by launching online branches or internet divisions. The various models fintech firms and traditional financial institutions are using to pair up or directly compete with each other are described below.

Fintech Ascendent

Whether teaming up with existing financial institutions or going it alone, fintech firms are rapidly gaining market share in several areas formerly dominated by financial institutions alone, such as payments and consumer loans. In 2013, fintech companies accounted for 5% of the personal loan market, according to Transunion. By 2018, fintech firms had eclipsed banks with a 38% share of a growing market. Banks’ share of personal loans fell from 40% to 28% over the same period, while credit unions’ share declined 10 percentage points to 21%.

Most fintech firms are not—and do not seek to be—full-service financial institutions. They do not meet the definition of a bank—an institution that both takes deposits and makes loans—and they do not have a banking charter, or license. Fintech firms typically market their narrow range of products to specific market segments such as students, small-business owners and freelancers. Some specifically seek to serve the under- and unbanked, who may not want or need a bank to meet some objective, such as savings, person-to-person payments and small-dollar loans. These firms frequently partner with traditional financial institutions using a variety of models that provide benefits for both providers. Chime, Dave and MoneyLion are among the industry’s leaders in transactions volume and number of users.

Other fintech firms have modeled themselves more like banks, with some seeking bank or bank-like charters to offer a suite of financial services. This trend has prompted some concern about unequal regulation and any resulting competitive advantages nonbank firms might gain. This is especially true of very large and dominant companies like Walmart, which filed a trademark application in March 2021 for a venture called “Hazel” that the company says could offer services such as credit card issuance, financial portfolio analysis and consulting, credit and debit card transaction processing, mobile payments and virtual currency transaction processing services. Walgreens has also made plans to get into banking by partnering with fintech firm InComm Payments. These retail giants are of particular concern to traditional bankers because of their strong brand recognition, widespread locations and heavy foot traffic.

Fintech firms that opt to obtain a banking license are called challenger banks; they are chartered, regulated financial institutions with brick-and-mortar locations and fintech-based services. Because challenger banks have bank charters, they can offer customers traditional banking services such as credit cards and mortgages, as well as those available through apps.

Other advantages of a bank charter include access to the Federal Reserve’s discount window and direct access to its payments system. But with those benefits comes more stringent oversight by federal or state banking supervisors and consolidated supervision by the Federal Reserve if the new bank is part of a bank holding company. One of the best-known challenger banks is Varo, which obtained a national bank charter in the summer of 2020.

Alternative Charters

A few fintech companies have sought and obtained industrial loan company (ILC) charters. ILCs are state-chartered financial institutions that have typically specialized in financing the products of a corporate partner, like an auto company. In exchange for their charters and access to the federal safety net—including federal deposit insurance, the Federal Reserve discount window and the payments system—ILCs must comply with federal safety and soundness and consumer protection laws that apply generally to institutions insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC).

ILC parent companies that are nonfinancial in nature are not supervised by the Federal Reserve. This feature, among others, has made ILCs controversial, and the FDIC imposed a moratorium on new deposit insurance applications between 2006 and 2008, when Walmart and Home Depot both sought them. Another three-year moratorium was imposed in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010.

In the past several years, a number of fintech firms have expressed interest in obtaining ILC charters, and the FDIC has approved deposit insurance applications for Square, a payments service provider, and Nelnet, an originator and servicer of student and other consumer loans. Several applications remain in the pipeline.

Another potential way for fintech companies to offer banking services without partnering with a bank or obtaining a banking charter is the special-purpose bank charter. In 2018 and again in 2020, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) announced fintech firms could apply for special-purpose national bank charters; the charter proposed in 2018 was geared toward lenders, while the 2020 version was targeted to payment companies. The authority of the OCC to issue these charters has been challenged, and cases are winding their way through the court system. The Federal Reserve is evaluating guidelines that would permit special-purpose chartered institutions to open accounts and access payment services at the Fed.

Banks Respond

The technological developments that spawned fintech, such as big data and artificial intelligence, have also greatly benefited traditional financial institutions, regardless of whether they have a contractual relationship with a fintech firm. Innovation has launched new products, spurred efficiency and lowered costs for everyone.

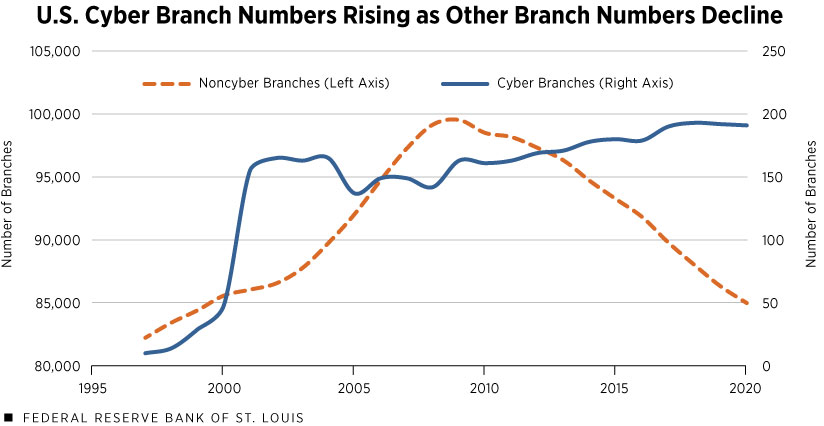

One such development is the so-called “cyber branch.” Cyber branches, unlike their brick-and-mortar counterparts, do not have physical locations; all transactions are conducted online or over the phone. And while they are small in number now, their ranks are bound to grow as banks look to cut costs and reach new customers in a more competitive financial services landscape.

Although the number of brick-and-mortar branches peaked near 99,400 in 2009, the number of cyber branches has more or less risen steadily since the late 1990s. According to the FDIC, branches classified as “full service, cyber offices” increased from nine in 1997 to 190 in 2020. They now account for more than 4% of total deposits, while only accounting for 0.2% of the nation’s 85,000 total bank branches. On average, cyber branches are larger than their physical counterparts.

In 2020, the average cyber branch had $3.5 billion in deposits compared with $176 million for noncyber branches. Banks with the largest cyber branches are household names: Charles Schwab, Ally Bank, USAA Federal Savings Bank and E-Trade. But most cyber branches are relatively small, with median deposits of $11 million in 2020.

SOURCE: Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Summary of Deposits data, 1996-2020.

Some banks have used their cyber branches to launch separately branded online banking (SBOB) divisions. These divisions or subsidiaries have different names—and web addresses—than their head offices. They not only permit banks to expand their customer bases beyond the physical locations of their head offices and branches but also can serve as forums to audition or highlight particular deposit, loan or investment products and services or draw in different types of customers.

Approximately 40 U.S. banks of all sizes had operating SBOB divisions as of June 2019.These data are taken from Neil Wiggins and Dasha Basnakian’s 2020 article, “A Survey of Separately Branded Online-Only Banks and Their Role in the Banking System.” The authors used Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (call reports) data to create a subset of banks that reported non-parent bank URLs (websites) associated with the parent bank. That list was then pared down, removing URLs of brokerage sites, social media sites and retained URLs from mergers. The average asset size of their parent banks was $56 billion, but nearly a dozen had assets of less than $1 billion. Some offer a full suite of banking products, while others specialize in products such as vacation home loans or health spending accounts. Several cater to specific types of customers such as physicians or universities.

One of the more colorful examples of an SBOB is Redneck Bank, the digital division of Oklahoma’s All America Bank. Redneck’s website announces that not only is it a real bank, but it’s a bank “where bankin’s funner!” Since its 2008 launch, Redneck has offered high-yielding basic bank accounts along with humor and has garnered depositors across the country. The community bank’s owners moved forward with the low-cost concept, knowing they could shutter the Redneck brand if it flopped without damaging the parent bank’s reputation. That same calculus is no doubt behind the decisions of other bankers who have gone the SBOB route.

Where the Digital Future Is Heading

The growth of fintech means consumers and businesses with ready access to the internet have more choices than ever for deciding where, when and with whom they will bank. For many customers, especially younger ones, activities associated with banking—deposits, loans, payments and investments—will likely be split among many different types of bank and nonbank firms. Some may never enter a bank lobby or speak to a banker.

Banks of all sizes are teaming up with fintech partners or experimenting with bigger digital footprints to reduce costs and compete in the digital banking space. But there is no evidence that the brick-and-mortar bank branch is going away anytime soon. Although pandemic-related branch closures prompted many bank customers to use online and mobile banking services for the first time, many if not most turned to their local bank branches by phone or in person when they reopened. And banks are still opening new branches even as others are closed. How much and how fast consumers adapt to the financial technology revolution will determine what the banking industry looks like decades from now.

Endnotes

- Venmo and PayPal are two well-known fintech firms that use fintech to facilitate person-to-person payments. LendingTree, a leading provider of home loans, is another example of a fintech firm. See this brief primer on fintech.

- These data are taken from Neil Wiggins and Dasha Basnakian’s 2020 article, “A Survey of Separately Branded Online-Only Banks and Their Role in the Banking System.” The authors used Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (call reports) data to create a subset of banks that reported non-parent bank URLs (websites) associated with the parent bank. That list was then pared down, removing URLs of brokerage sites, social media sites and retained URLs from mergers.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us