The Role of Age in Determining Stock-Bond Investment Mix

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The standard view says households should invest heavily in stocks when young and then shift to less-risky bonds as they grow older.

- One argument says young people should follow this advice because they have a long investment horizon. Another attributes this view to the longer work life of young people.

- Yet U.S. households don’t appear to follow this investment pattern, according to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances.

There is a standard view that as one becomes older, it is prudent to invest more in bonds and less in stocks. The stock market is seen as a young person’s game, while the bond market is considered to be more conservative and better suited to the needs of soon-to-be retirees.

But what really motivates this view? The question is rather technical, requiring significant knowledge in finance and mathematics. This article, however, will explore two often-cited arguments in a nontechnical way, discuss their validity and finally present the facts.An excellent article published in 1996 by economists Ravi Jagannathan and Narayana Kocherlakota discusses this question at a technical level. I have relied extensively on their analysis for this article.

The Theory

The logic behind this view is rooted in the fact that stocks generally outperform bonds over long periods of time, even though stocks are riskier than bonds. For instance, from 1889 to 1978, the annual real return on U.S. Treasury bills (a riskless bond) averaged 0.8 percent, while the annual real return on the S&P 500 (a collection of risky stocks) averaged 6.98 percent.See Mehra and Prescott.

To put these numbers in perspective, imagine a 20-year-old with $1,000 to invest. Investing it all in the riskless bond for 20 years would yield about $1,173, while investing it all in the risky S&P 500 for 20 years would yield $3,855. Clearly, despite the risk, investing in stocks seems the better choice, but who can wait for 20 years? The young.

Yet the logic above is incomplete for two reasons. First, it is true that stocks outperform bonds in the long run, but the potential for a disastrously bad outcome when investing in the stock market also increases as the horizon of the investment increases. If households are very sensitive to risk, they will perceive potential losses as a negative feature of the stock market.

In other words, young people with a strong enough dislike for risk will view the stock market as too risky because they are young (and thus have a long investment horizon) and they are focused on the potential for disaster. On the other hand, young people willing to take risks will view the stock market as less risky because they are young and they are focused on the potential for growth.

Second, households can change their portfolio composition at any time, albeit at a cost; therefore, a household’s investment horizon is only as long as the interval between changes to its portfolio. This implies that there is, for all intents and purposes, no difference between a long and a short investment horizon: A young household does not have to keep a constant share of its investment (possibly all of it) in the stock market for 20 years but may choose to do so by electing, annually, to keep its portfolio composition constant. There’s no such thing as a “long” horizon when the portfolio can be readjusted annually.An example can help to illustrate this point: Suppose that the safe rate of return is 1 percent, while the stock market return is –10 percent for the coming year and +10 percent forever after. Suppose also that people “foresee” these returns. The best investment strategy is to invest for 1 year in bonds only, and then readjust the portfolio to invest in stocks only. This is true regardless of the number of years the investment might last, i.e., the “horizon.”

Thus, if young households should indeed invest more in stocks than in bonds, the reason cannot be that they have a longer time horizon than the old. Let us then turn to another, better argument.

To understand this argument, it is worth taking a small detour and defining what economists mean by “wealth.” A financial asset is worth a certain amount of dollars, say $100, because it is supposed to generate income streams in the future. These future income streams can take the form of interest payments to bondholders or dividends to stockholders.

When buyers are willing to pay $100 to acquire the asset, it means that they currently value the future stream of dollars from this asset at $100. Thus, the value of the asset—or, equivalently, the wealth of the asset holder—is determined by the future income promised by the asset, and this, in turn, is reflected in the current price of the asset.

Most people do not receive all their income from financial assets, though. They also work. A person’s work can be viewed as an asset because it is the source of future income. Economists refer to this notion as “human capital wealth,” i.e., the value of a worker’s future income stream. In fact, the labor income of the average worker is much less risky than the stock market, and therefore, human capital can be viewed more as a bond than as a stock.

Unlike a financial asset, however, a person’s human capital wealth decreases with age and becomes zero upon retirement, i.e., no labor income is to be generated after retirement. With this view in mind, a person’s wealth is the sum of his financial wealth and his human capital wealth. The best portfolio allocation should be decided by taking into account human capital wealth and the fact that this wealth approaches zero as retirement becomes imminent.

Specifically, consider a household that finds it’s best to split its wealth 50-50 between risky and riskless investment at any age. When the household is young, human capital wealth—which is nearly riskless—is large.Labor income is not completely riskless, of course. There is the risk of becoming unemployed for some period of time. But this risk turns out to be relatively small compared to the fluctuations of the stock market and is sometimes compensated by unemployment insurance. Hence the household needs more stocks than financial bonds to achieve its 50-50 goal. Upon reaching retirement, however, human capital wealth approaches zero, and financial bonds must be used to achieve a 50-50 goal. This is a valid reason why young households should hold more stocks than older households.

The Reality

What do U.S. households actually do then? The Federal Reserve Board and the U.S. Department of the Treasury sponsor a triennial survey, known as the Survey of Consumer Finances. The survey asks a representative sample of U.S. families questions about their finances in order to gather information on income, savings and investment by household.

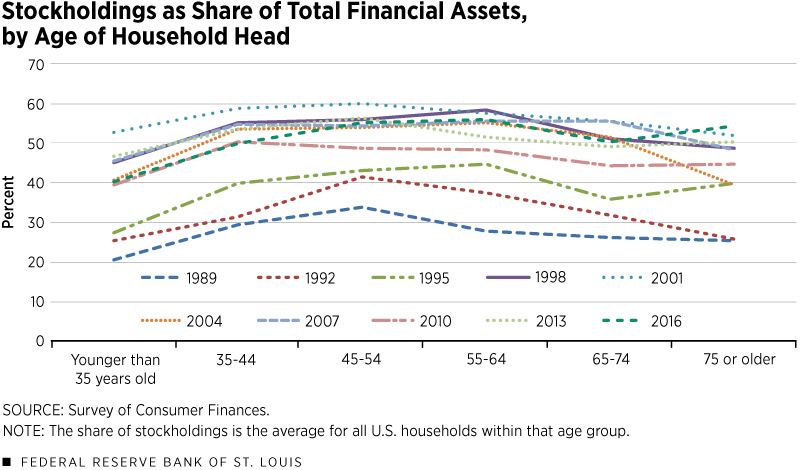

Figure 1 gets at the core of the question: It plots the fraction of a household’s financial assets that is invested in the stock market, either directly or indirectly. Each line represents a different survey year.

The message from Figure 1 is that a clear pattern linking the age of the household’s head and the stock-versus-bond composition of the household’s financial assets is missing. That is, there are no clear trends indicating that older households hold proportionally less stock than young households. In 2016, for instance, the household whose head was younger than 35 held 40.2 percent of its assets in stocks, while the household whose head was in the age range of 65-74 held 50.2 percent of its assets in stocks.

If anything, the relationship between age and portfolio composition is the opposite of what is prescribed by economic reasoning. Does this mean that the logic described earlier is wrong? Does it mean that U.S. households make wrong choices? Probably neither of the above explains the inconsistency. Instead, this suggests that there are determinants other than age in the decision to acquire stocks versus bonds. This is still an active, fairly technical, area of research.

Makenzie Peake, a research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, provided research assistance.

Endnotes

- An excellent article published in 1996 by economists Ravi Jagannathan and Narayana Kocherlakota discusses this question at a technical level. I have relied extensively on their analysis for this article.

- See Mehra and Prescott.

- An example can help to illustrate this point: Suppose that the safe rate of return is 1 percent, while the stock market return is –10 percent for the coming year and +10 percent forever after. Suppose also that people “foresee” these returns. The best investment strategy is to invest for 1 year in bonds only, and then readjust the portfolio to invest in stocks only. This is true regardless of the number of years the investment might last, i.e., the “horizon.”

- Labor income is not completely riskless, of course. There is the risk of becoming unemployed for some period of time. But this risk turns out to be relatively small compared to the fluctuations of the stock market and is sometimes compensated by unemployment insurance.

References

Jagannathan, Ravi; and Kocherlakota, Narayana. Why Should Older People Invest Less in Stocks Than Younger People? Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Summer 1996, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 11-20.

Mehra, Rajnish; and Prescott, Edward C. The Equity Premium: A Puzzle. Journal of Monetary Economics, March 1985, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 145-61.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us