Perceived Bias and Income Patterns Differ by Race

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Concentrating on perceived discrimination in economic research is uncommon, yet it allows for highlighting experiences that cannot be readily seen or directly measured.

- Non-Hispanic whites who do not feel they are discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity have the highest median real household income.

- Blacks who perceive discrimination have a higher median income than blacks who do not.

Racial differences in income have been very well-documented; whites consistently have better financial outcomes than blacks.See Emmons et al. Why are these differences present, and why are they so persistent?

While there are many valid hypotheses, this article focuses on an intangible variable: perceived racial discrimination (that is, a person’s belief that he or she is being treated unfairly due to race). I explore how perceived discrimination varies by race and how both are related to income. The findings are provocative:

- Non-Hispanic whitesHereafter, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks are simply referred to as “whites” and “blacks,” respectively. who do not feel they are discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity (the vast majority)Seventeen percent of whites in the American Identity and Representation Survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race, and 6 percent of whites in the Americans’ Changing Lives survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity. are the best off financially. Their median real household income is the highest.

- Whites who do feel they are discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity are not always financially better off than blacks. These whites can also be worse off than whites who don’t perceive bias.

- Perceived discrimination appears to work in the reverse manner for blacks: Blacks who perceive discrimination (a much larger proportion than whites)Sixty-five percent of blacks in the American Identity and Representation Survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race, and 40 percent of blacks in the Americans’ Changing Lives survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity. have a higher real median household income than blacks who do not.

These findings point to the importance of considering the potential impact of subjective perceptions when studying financial decisions and outcomes.

Why Perceived Discrimination?

Focusing on discrimination in economic research is not unusual, but concentrating on perceived discrimination is less common. In doing so, researchers can highlight an “unobservable” factor: an individual’s experience that is not readily seen or directly measured.

This research, therefore, places less emphasis on reality (whether discrimination actually occurred) and more on perception (whether someone thinks he or she experienced discrimination). This distinction is important because perceptions add an explanatory layer above that of reality alone. People tend to act on their perceptions—even if these may not reflect reality. For example, if people only believe there will soon be a shortage of a material good, they may hoard that good, thus causing a shortage.This is an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. See Merton.

In this research, I focus on the role of perceived discrimination because it may influence decision-making and ultimately financial outcomes like income.

Race and Perceived Bias

This article uses two datasets: the American Identity and Representation SurveyThe AIRS is provided by Resource Center for Minority Data. Data were weighted using WEIGHT1. Note that household income was given as a range of values. (AIRS) and the Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) survey.The ACL is maintained and distributed by the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging,sponsored by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health. Analyses used a log transformation of household income with outliers removed.

The AIRS, conducted in 2012, measured household income and delved into perceived discrimination with the question “Have you ever been treated unfairly at work, school, or when you’re out in public because of your racial background?”

In contrast, the ACL is a longitudinal dataset, which means the same people are surveyed over time. Perceived discrimination was measured with the question “Now thinking over your whole life, have you ever been treated unfairly or badly because of your race or ethnicity?”

Given that the ACL is longitudinal, I was able to explore the relationship between perceived discrimination measured in 1994 and household income measured in 2011.

Leveraging both surveys, I asked an intriguing question: Do white/black differences in income vary by perceptions of discrimination? I predicted they would but was surprised by some of the findings. I expected that when blacks and whites felt discrimination, they would have lower levels of income than their less-stressed counterparts. The reality was more nuanced.

The general finding that whites are financially better off than blacks was replicated and obvious. Whites’ median household income was roughly double the income of blacks.In the ACL, the median white household income was $57,200, and the median black household income was $28,600 (2018 dollars, rounded to the nearest $100). In the AIRS, the median range of white household income was between $66,701 and $83,400, and the median range of black household income was between $41,500 and $47,400 (2018 dollars, rounded to the nearest $100).

When factoring in perceived discrimination, however, the results were somewhat less conclusive. Whites were not always uniformly better off than blacks.

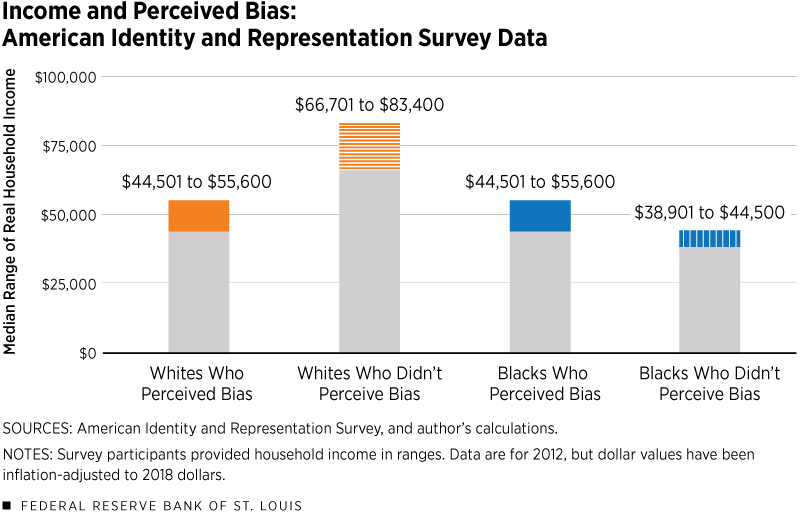

In the AIRS, whites who didn’t think they were discriminated against because of their race were better off than all other groups: whites who did perceive discrimination and blacks, regardless of perceived bias.

However, whites who did feel they were discriminated against had a median range of household income equivalent to the typical black who also felt discrimination. (See Figure 1.)

Within-Race Income Comparisons

I found evidence supporting the differential effects of perceived discrimination by race. While the results were mixed for whites, the effects were clear for blacks, though in an unexpected way.

In the AIRS, whites sensing no discrimination had a higher median range of real household incomeIncome in both datasets has been adjusted to 2018 dollars using the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U). (between $66,701 and $83,400) than their white counterparts who did feel they were discriminated against because of their race (between $44,501 and $55,600). I expected this pattern.

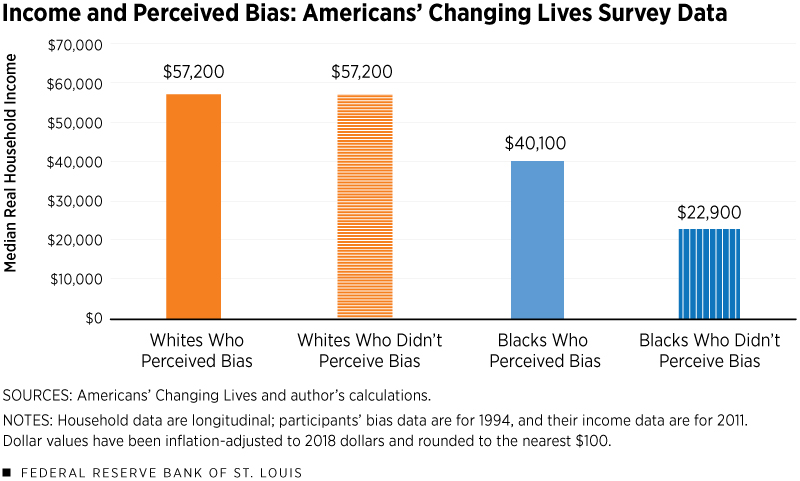

In the ACL survey, perceived bias in 1994 did not have a relationship to household income in 2011 for whites; their median real household income was $57,200 regardless of felt discrimination.

However, the pattern of results for blacks in both surveys turned these findings on their head. Blacks who felt they were discriminated against because of their race actually had higher median incomes than blacks who didn’t feel racial bias.

In the AIRS, blacks who did not feel they had been discriminated against had a median range of household income that was between $38,901 and $44,500; if they did feel they had been discriminated against, the median range was between $44,501 and $55,600. (See Figure 1.) In the ACL survey, those figures were $22,900 and $40,100, respectively. (See Figure 2.)

Conclusion

An abundance of economic research shows that blacks clearly face poorer financial outcomes than do whites.See Emmons et al. That general result was replicated here. Yet, accounting for perceived discrimination gives additional information. Looking at only blacks, felt discrimination appears to be related to improved financial outcomes. Of course, it is of utmost importance to note the difference between correlation and causation. For blacks, these datasets showed that perceiving bias was correlated with (but did not necessarily cause) higher incomes.

In both surveys, blacks who perceived racial discrimination had higher household incomes than those who did not. This result goes against conventional wisdom and supports the use of subjective variables, such as perceived discrimination, when studying financial outcomes. Further research is needed to understand these findings.

Nevertheless, in all but one comparison, blacks’ household incomes were lower than those of whites, highlighting the ubiquity of racial disparities in financial outcomes.

Endnotes

- See Emmons et al.

- Hereafter, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks are simply referred to as “whites” and “blacks,” respectively.

- Seventeen percent of whites in the American Identity and Representation Survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race, and 6 percent of whites in the Americans’ Changing Lives survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity.

- Sixty-five percent of blacks in the American Identity and Representation Survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race, and 40 percent of blacks in the Americans’ Changing Lives survey felt they were discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity.

- This is an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. See Merton.

- The AIRS is provided by Resource Center for Minority Data. Data were weighted using WEIGHT1. Note that household income was given as a range of values.

- The ACL is maintained and distributed by the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health. Analyses used a log transformation of household income with outliers removed.

- In the ACL, the median white household income was $57,200, and the median black household income was $28,600 (2018 dollars, rounded to the nearest $100). In the AIRS, the median range of white household income was between $66,701 and $83,400, and the median range of black household income was between $41,500 and $47,400 (2018 dollars, rounded to the nearest $100).

- Income in both datasets has been adjusted to 2018 dollars using the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U).

- See Emmons et al.

References

Emmons, William R.; Kent, Ana H.; and Ricketts, Lowell R. The Bigger They Are, The Harder They Fall: The Decline of the White Working Class. The Demographics of Wealth 2018 Series, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, September 2018, Essay No. 3.

House, James S. Americans’ Changing Lives: Waves I, II, III, IV, and V, 1986, 1989, 1994, 2002, and 2011. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Aug. 22, 2018. See https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04690.v9.

Merton, Robert K. The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. The Antioch Review, Summer 1948, Vol. 8, Issue 2, pp. 193-210.

Schildkraut, Deborah. American Identity and Representation Survey, 2012. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], July 22, 2016. See https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36410.v1.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us