Women Affected Most by COVID-19 Disruptions in the Labor Market

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The COVID-19-induced recession of 2020 was different from others because it was caused primarily by efforts to slow the new virus’ spread.

- Industries hit particularly hard included those requiring close contact with other workers and members of the public.

- Women saw greater unemployment because many work in high-contact or part-time jobs. Child- and elder-care issues also may have contributed.

From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic—as copious flows of data were generated and processed—a striking gender bias emerged: It became apparent that the novel coronavirus was, and still is, killing men at significantly higher rates than women.

A lesser-known and discussed—but equally striking—fact is that virus-related labor market disruptions have not been gender-neutral, either. The pandemic has affected women’s employment status much more significantly than men’s.

In this article, we show the negative impact of COVID-19 on working women and argue that, to understand this asymmetry between genders, we need to look at two disparate trends surrounding women’s participation in U.S. labor market.

This Time Is Different

The COVID-19-induced recession of 2020 was very different from other recessions in recent memory. By its nature, it was not a proper recession because it was caused by government policies and private sector responses to counter the spread of the virus—not by a disruption in the production sector or the collapse of financial markets.

In any event, vast sectors of the service industry were directly affected by the economic contraction caused by social distancing and lockdown protocols. In turn, many other sectors were indirectly affected by lower demand and disruptions in supply. While closed restaurants, online schools and empty airports epitomized the economy in 2020, the disruptions have been much broader.

The latest recession has been different from previous ones because it has severely hit industries and occupations that require close physical contact. These jobs are in sectors such as health care, education and hospitality, which tend to have high female employment shares.

This is quite different from previous recessions that disproportionately reduced jobs in the traditionally male-dominated construction, transportation and manufacturing sectors. At the macro level, these differences are easy to detect. In a typical recession, the unemployment rate for male workers increases much more than for female workers.

For instance, in the Great Recession, which fell within the May 2007 to November 2009 time frame, the unemployment rate for men increased from 4.6% to 11%; for women, it went from 4.4% to 8.6%. In contrast, in January 2020, the unemployment rate for both genders was 3.5%; by April 2020, it had climbed to 16.1% for women and 13.6% for men.Nonetheless, as noted in a previous article, in the Great Recession of 2007-09, long-term unemployment for women was already on par with that of men. See “Age and Gender Differences in Long-Term Unemployment: Before and after the Great Recession.”

In addition, even in the modern era, caring for children and the elderly falls disproportionately on women. So, the closures of schools and all other centers that care for children and seniors are likely to have further reduced—perhaps enormously—the labor market opportunity for many women.

Two Existing and Disparate Trends

Two important trends must be discussed to help identify a pattern for these unequal effects. On one hand, the past several decades have witnessed a strong trend in which highly educated women are entering the labor market. On the other hand, women still account for an enormous and steady share of part-time jobs, which are relatively insecure.

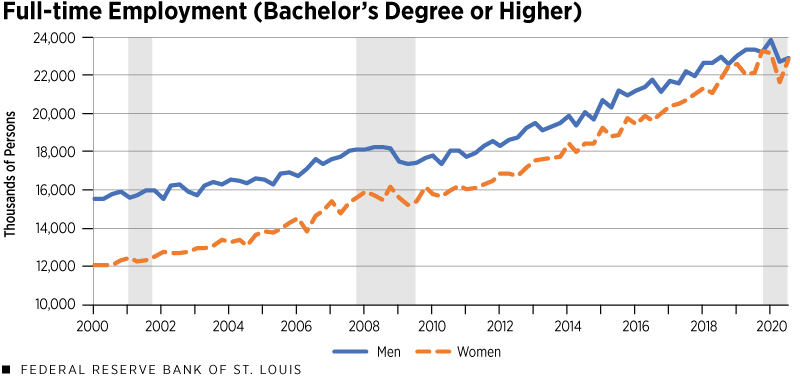

First, there is a strong trend in the upper end of skill distribution, with women entering and even dominating high-paying occupations. Indeed, despite substantial gaps still remaining, as a group, women have been consistently achieving significant gains in participation and outcomes in the U.S. workforce. This positive trend has multiple dimensions, including a much higher participation rate for women in highly skilled and high-earning occupations, as shown in the figure below.

The figure shows the numbers of men and women employed full time who are older than 25 and have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Early in 2000, there was a large gap between the numbers of full-time college-educated men and women workers, with women accounting for only 44% of the labor market. By late 2019, right before the COVID-19 pandemic began, this gap had shrunk significantly, with both genders sharing 50% of the labor market.

This is consistent with previous findings that, since 2015, white women have outnumbered white men in professional occupations. Since professional jobs can be performed more easily from home, one would expect the COVID-19 crisis would not affect women more severely than men, at least from a labor market perspective. If so, all the asymmetries in the upper end of skill distribution might be explained by an uneven division of labor inside households, in terms of caring for children, the elderly and the sick.

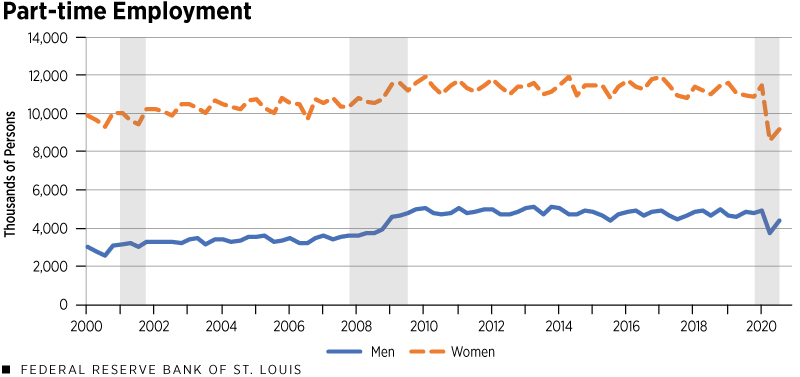

On the other hand, women account for a large and persistent share of people with part-time jobs in the U.S. labor market, especially in the lower end of skill distribution.Similar patterns are observed in other developed countries as discussed in a recent article in The Atlantic. The second figure below shows the numbers of men and women working part time who were older than 25.

In the first quarter of 2000, women accounted for more than 75% of the part-time labor market. By 2019, women still accounted for almost 70% of part-time workers. Those part-time jobs tend to be relatively insecure, and many are in service sectors that also happen to require high amounts of physical contact among workers and with customers.

COVID-19 was probably the perfect storm for many women in these jobs, especially those with families. The figure shows a steep fall in these types of jobs, and, at least from the current observations, a much slower labor recovery for women than for men. Furthermore, the unemployment rate increased substantially more for women of color than for white women.

In sum, in addition to the remarkable asymmetry between men’s and women’s job losses, the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities for women in the labor force, as dictated by their skill levels and occupations.

Endnotes

- Nonetheless, as noted in a previous article, in the Great Recession of 2007-09, long-term unemployment for women was already on par with that of men. See “Age and Gender Differences in Long-Term Unemployment: Before and after the Great Recession.”

- Similar patterns are observed in other developed countries as discussed in a recent article in The Atlantic.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us