Changing Trade Relations May Affect U.S. Auto Exports in Long Run

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Concerns about the U.S. auto industry have helped spur the U.S. to revamp its trade relations.

- Yet continued U.S.-China trade disputes could leave U.S. automakers without access to the world’s biggest auto market in terms of sales volume.

- USMCA, the proposed trade deal that replaces NAFTA, may also make U.S. vehicles less competitive in the global market.

The U.S. has one of the world’s largest auto markets, yet some are worried that free trade has disadvantaged the country’s competitiveness in automotive production. The recent renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) exemplifies this concern, because trade rules for the auto sector received an overhaul.

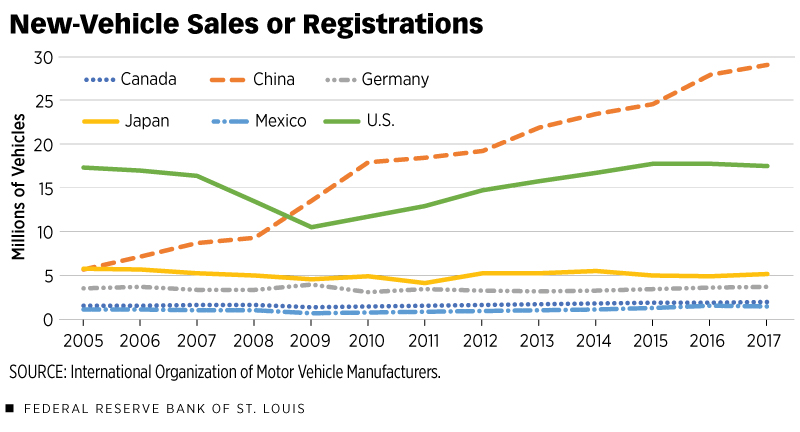

However, focusing solely on auto trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico ignores the elephant in the room—China, home to the world’s largest auto market in terms of units sold. (See Figure 1.) U.S. automakers may miss a huge opportunity in this rapidly growing market if U.S.-China trade disputes linger and if new North American trade rules make U.S. auto exports more expensive.

In this article, we will evaluate the effects of the North American trading bloc on the U.S. auto trade, look at the current landscape of the global auto market and explore the repercussions of further disruptions to trade.

NAFTA’s Impact on Auto Trade

NAFTA was implemented on Jan. 1, 1994, with the goal of reducing barriers to trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Numerous tariffs were eliminated, and intellectual property rights on traded products were protected.

NAFTA was a huge victory for free trade at the time, but America’s past commitment to free trade is now being questioned. There is concern that the persistent U.S. trade deficit led to a loss of manufacturing jobs and that the terms of NAFTA disadvantaged U.S. factory workers. As a result, NAFTA was renegotiated, and a new deal called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was formally signed at the G-20 meeting in Argentina on Nov. 30, 2018; the U.S. Congress still has to ratify the new agreement. Although many provisions in NAFTA will be unchanged, the auto trade rules will be significantly revised.

In 1994, the U.S. ran a real trade deficit of $63 billion (in 2012 dollars) in motor vehicles, and this deficit had nearly doubled by 2017. We also see that the U.S. trade deficit in vehicles has widened with major car manufacturing nations. This is not to attribute the rising trade deficit in vehicles solely to NAFTA as the overall U.S. trade deficit has increased nearly sixfold since 1994. But looking solely at the trade deficit tells only part of the story.

From 1994 to 2017, both U.S. exports and imports in autos doubled in terms of value, i.e., exports and imports increased in the same proportion. This suggests that the increase in auto imports has not crowded out auto exports. Although imports and exports in vehicles increased in the same proportion, the auto trade deficit still doubled because the U.S. was already running a trade deficit in vehicles in 1994. This rising auto trade deficit doesn’t necessarily imply that the competitiveness of the U.S. auto sector has been affected.

Also, the size of the U.S. economy as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) has almost doubled since 1994—a similar increase to what the U.S. auto trade deficit has undergone. Although the overall auto trade deficit as a percentage of GDP increased until 2000, it has since declined and is now near its 1994 level. Therefore, the auto trade deficit relative to the size of the economy remains unchanged since the signing of NAFTA.

Concluding that NAFTA has hurt U.S. auto manufacturing by looking solely at the increasing deficit in vehicles is very misleading. The proportion of imports to exports and the size of the deficit relative to GDP have been fairly constant since the commencement of NAFTA. The U.S. was already running a trade deficit in vehicles in 1994, so as the U.S. economy grew, this deficit widened despite the fact that the ratio of imports to exports was unchanged since the signing of NAFTA.

USMCA and Autos

The proposed trade agreement USMCA will not drastically change much of NAFTA, but auto trade rules will be significantly changed. For example, 75 percent of auto parts must be manufactured in North America to qualify for zero tariffs starting in 2020, up from the present level of 62.5 percent. This large increase will lead to major shifts in supply chains in a short period of time to avoid tariffs.

Also, at least 30 percent of the work on vehicles must be done by workers earning at least $16 per hour. This share of work will then increase to 40 percent by 2023. This could benefit U.S. workers since they earn higher wages than workers in Mexico, but it would also increase the cost of cars made in North America. In the long run, this could lead to decreased global demand for cars manufactured in North America as they become less competitive in a global market, which could ultimately hurt U.S. autoworkers. Based on our previous analysis, USMCA is a solution searching for a problem in regard to auto trade. It also could make North American automakers less competitive in a global marketplace.

The Current U.S. Auto Market

U.S. auto sales totaled about 17 million units in 2017. The U.S. is also one of the world’s largest auto importers: About 8 million vehicles were imported in 2017. Thanks to NAFTA, Mexico and Canada are the largest U.S. trading partners in vehicles. In 2017, the U.S. exported about 1 million vehicles, in total, to Canada and Mexico and imported about 4 million vehicles from Canada and Mexico.

Figure 1 shows that vehicle sales have been fairly constant since 2005 for Canada, Germany, Japan, Mexico and the U.S. (except for a dip during the Great Recession), suggesting that these countries’ auto markets are saturated. A saturated market suggests that auto manufacturers will have to look for other markets to find growth opportunities.

U.S. vehicle sales also hit a record high in 2016, then dipped in 2017. If American auto manufacturers anticipate this trend to continue, then they may also look to shift production abroad to better match global demand.

Although auto markets in these developed nations are saturated, China’s auto market has increased fivefold since 2005, reaching nearly 30 million in 2017. This is about as large as the combined markets of Canada, Germany, Japan, Mexico and the U.S.

China provides a great opportunity for growth for U.S. auto producers; however, if USMCA makes North American auto manufacturers less competitive, they could miss out on a huge growth opportunity. Yet, USMCA may be an insignificant problem for U.S. automakers if a full-out trade war between China and the U.S. breaks out. If U.S. auto manufacturers are completely excluded from competing in China—the largest auto market in the world—then their potential growth could be seriously hindered.

Conclusion

Although the U.S. trade deficit in vehicles has increased since 1994, NAFTA does not seem to have impacted U.S. auto trade negatively. But USMCA could potentially hurt North American automakers’ competiveness in a global environment.

Furthermore, the Chinese auto market is huge relative to the North American market, but China is essentially self-sufficient and satisfies its auto demand through domestic production. Most automobiles sold in China are foreign brands, with U.S. car brands accounting for about 11 percent of the Chinese market.

If American auto manufacturers produce cars in the U.S. and ship them to China, they would not be competitive with other foreign automakers operating in China because of high production and shipping costs. If the U.S. manufacturers cannot compete in this market, then their growth will be hampered, which could ultimately hurt autoworkers and possibly offset any benefits that these workers could gain under USMCA. Hence, trying to incentivize U.S. manufacturers to move production back to the U.S. and then export to countries like China is not economically feasible.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us