Social Changes Lead Married Women into Labor Force

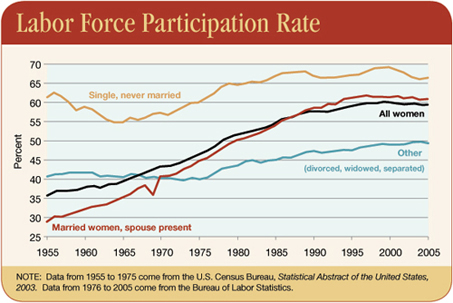

The female labor force participation rate—the percent of civilian women who are in the labor force—has increased so much over the last 50 years in large part because many more married women are working.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau show that from 1955 to its peak in 1999, the labor force participation (LFP) rate for all women increased by 24.3 percentage points. The attached figure shows that the rate for married women has more than doubled since 1955, while the rates for the other two groups have increased by much less.

Several theories try to explain this rise in married women's LFP.1

In this article, we focus on whether social impetus—in particular, changes in intra-marital relationships—can explain the rise. We explore three hypotheses suggested by economic studies: adoption of advanced technology, changes in marital preferences and use of the birth control pill.

Household Production

Social attitudes toward women and their role in society have changed since World War II ended. However, economists Jeremy Greenwood, Ananth Seshadri and Mehmet Yorukoglu have argued that married women could not enter the labor force in large numbers until housework had become less time-consuming. Specifically, the authors focused on widespread adoption of advanced technology—e.g., washing machines, vacuums and dishwashers—that greatly reduced the time needed for housework.2

Greenwood, Seshadri and Yorukoglu imagined a household made up of a male who always works in the labor market and a female who always does the housework. The couple decides whether the woman also should work outside the home. The authors then determined the effects on women's LFP of technological adoption, of the decreasing gap between men's and women's wages, of the interaction of technology and wages, and of the falling price of technology (which spurs widespread adoption). They found that more than half of the increase in women's LFP was due to labor-saving technology. Only one-fifth of the increase was directly due to the declining gender-wage gap, while the remainder was caused by the interaction of the two variables.

These results show that the technology was necessary to free women's time before a better outside option could encourage them to join the labor force.

Working Mothers, Working Wives

In their 2004 study, economists Raquel Fernández, Alessandra Fogli and Claudia Olivetti hypothesized that men with working mothers were more likely to have working wives. A son's preference to marry a woman who works may have been influenced by having a working mother. Also, a working mother could make her son more productive with household chores, thus allowing his wife more time for work outside the home.

To test their theory, the authors used two datasets. One included white men whose wives were 30-50 years old when the survey was taken. After controlling for some background characteristics, Fernández, Fogli and Olivetti found that the probability that a married woman worked full-time (at the time of the survey) was 32 percentage points higher if her husband's mother worked for at least one year when he was young.3

Using the other survey, which includes more background information on the wife, the economists wanted to see if a mother's decision to work also affects her daughter's decision to work. If so, the relationship between having a working wife and a working mother might simply be due to marriages among couples in which both mothers worked. This sample included white couples who were 55 years old or younger when they were interviewed in 1980. Here, the authors defined a working mother as one who worked "all the time" when the husband/wife was growing up. Surprisingly, after controlling for other variables, the wife's work decision was unaffected by her own mother's labor force status. As with the first survey, the probability that the wife worked full-time increased by 24 percentage points if her husband's mother worked "all the time."

World War II data enabled Fernández, Fogli and Olivetti to determine how mothers' increasing LFP can affect subsequent generations. Different troop mobilization rates across states meant that some states saw larger increases in married women's LFP than others, where female LFP increased more in states with higher mobilization rates. The increases affected some groups of women temporarily and others permanently. To determine when increases in LFP of married women became permanent, the authors examined married white women who were 45-50 years old in different years: 1950, 1960, 1970 and 1980, the last of which represents those who were 7-12 years old during the war.4

States with higher mobilization rates had higher LFP among these women only in 1950 and in 1980. The increase for the former group was directly because of the war. For the latter group, the authors estimated that 16 percent of the increase in weeks worked was due to higher mobilization rates. These are the women who grew up in the new type of family where their (and their husbands') mothers had higher rates of LFP. Therefore, they were the first group of married women for which the increase in LFP due to the war was permanent.

The Pill

A 2002 study by economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz focuses on the birth control pill as a factor in women's increased LFP because it altered the timing of marriage and pregnancy. The pill was first made available, primarily for married women, in 1960. Widespread adoption among young, unmarried women, however, varied by state.5

Goldin and Katz argued that the pill's availability to young, unmarried, college-aged women increased women's career investment and, hence, long-term LFP. Without the pill, young women who wanted professional careers would have to practice abstinence or face uncertainty regarding pregnancy. The pill, in contrast, meant that women did not have to choose one or the other, which lowered the cost of delaying marriage and investing in a long-term career.

The effect of the pill's availability on the workforce decisions of young, single women is reflected in the different marital decisions across groups. Compared with those born in 1940-49, the proportion of female college graduates born in 1950-54 who were married by age 23 declined by 8.7 percentage points, according to Goldin and Katz. Access to the pill by age 17 had a strong impact, lowering the fraction married by 3.2 percentage points, or 37 percent of the total decline.6

As for long-term career investments, Goldin and Katz estimated an increase of five percentage points in the share of 30- to 49-year-old women in professional occupations between 1970 and 1990.7

Approximately 1.7 percentage points—about one-third of the total increase—can be attributed to increased pill use. The pill explains even more of the increase in the share of college women who were doctors and lawyers. Of the total increase of 1.7 percentage points, growth in pill use explains 1.2 percentage points, or nearly three-fourths of the total.

Discussion

A unifying theme in these articles is the reason for the change in female LFP. Each economic theory on increased LFP among married women comes from the idea that a working wife has become more attractive to married couples. In particular, each explanation centers on women having more marital bargaining power through spending less time on household chores, a changing social atmosphere or fertility delay. However, we considered only a few explanations and cannot conclusively identify the portion of the rise in female LFP attributable to each of these and other causes. Still, evidence from these studies reveals that, at times, innovations in economic behavior can result from social change.

Endnotes

- Goldin (1990, pp. 174-76) reported that the overt discrimination of not employing married women disappeared after 1950. She attributed this to the decrease in the availability of young, single female employees, stemming from the decline in the birth rate in the 1920s and 1930s, among other things. [back to text]

- The authors reported that in 1900, the average amount of time spent on housework was 58 hours per week but only 18 hours per week in 1975. [back to text]

- The authors used the following variables: the wife's age, education and work status; the husband's age, education and income; his total number of children and total under age 6; his parents' education; whether his mother worked for at least one year after he was born but before he turned 14; and the following when he was 16 years old: his religion, his family income, his place of residence (e.g., large city, farm, etc.) and his geographic region. [back to text]

- The basis for comparison was married white women who were 45-50 years old in 1940. [back to text]

- Unmarried women below the age of majority (21 years old in all but nine states in 1969) needed parental consent before obtaining the pill until later in the decade. By 1974, however, all but two states had an age of majority of 18 years old or at least had laws where minors did not require parental consent for the pill or other family planning services. As a result, beginning with the cohort of college graduate women born in 1952 and childless before age 23, about 35 percent had used the pill before age 21. [back to text]

- In their analysis, the authors controlled for access to legalized abortion, state and year of birth, and state-of-birth time trends since states adopted more feminist views, etc., at different times. [back to text]

- Teachers and nurses were excluded from the estimation. [back to text]

References

Fernández, Raquel; Fogli, Alessandra; and Olivetti, Claudia. "Mothers and Sons: Preference Formation and Female Labor Force Dynamics." Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2004, Vol. 119, No. 4, pp. 1,249-99.

Goldin, Claudia. Understanding the Gender Gap, New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Goldin, Claudia and Katz, Lawrence F. "The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions." Journal of Political Economy, August 2002, Vol. 110, No. 4, pp. 730-70.

Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth; and Yorukoglu, Mehmet. "Engines of Liberation." Review of Economic Studies, January 2005, Vol. 72, pp. 109-33.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us