Inflation Uncertainty among Eighth District Households

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Calculating the standard deviation—a statistical measure of dispersion—of households’ inflation expectations can serve as a gauge of their uncertainty about future inflation.

- Eighth District respondents to the Survey of Consumer Expectations were significantly more uncertain about the path of future inflation than U.S. respondents as a whole.

- Large increases in inflation uncertainty among Eighth District respondents appear to coincide with significant changes in the Fed’s target range for the federal funds rate.

In this article, we document the inflation uncertainty felt by households in the Eighth Federal Reserve District over time.The Eighth District, headquartered in St. Louis, includes all of Arkansas, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, northern Mississippi, eastern Missouri and western Tennessee. Specifically, we show that after the COVID-19 pandemic began, Eighth District respondents to the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) were significantly more uncertain about future inflation than respondents across the U.S. as a whole. Additionally, the large increases in inflation uncertainty in the Eighth District appear to coincide with significant increases and decreases in the federal funds rate target range set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the Federal Reserve’s main monetary policymaking body.

Inflation is an important issue for U.S. households; high inflation erodes purchasing power and causes consumers to spend more on important goods, such as food, energy and housing. Inflation also affects the real value of nominal contracts, such as mortgages, student loans or corporate bonds. Because these specify a set repayment amount in dollars, inflation means the money that the lender eventually receives will be worth less than the money that was originally lent out. For instance, if a household purchases a one-year corporate bond with a nominal interest rate of 2% and a year later inflation reaches 3%, the purchasing power of the bond payment is actually 1% less than the purchasing power of the money that bought the bond. When lenders and borrowers are relatively certain about future inflation, they can factor those expectations into the interest rate charged on nominal contracts. However, when households are relatively uncertain about future inflation, the real return is uncertain as well, and a loan or bond purchase becomes risky.

Tracking Inflation Uncertainty Using the SCE

To observe the evolution of inflation uncertainty in the Eighth District, we turn to data from the SCE. The SCE surveys a rotating panel of around 1,300 nationally representative heads of households. The same individual will generally be surveyed in multiple periods. The SCE asks respondents how likely they perceive different levels of inflation to be in the coming year. For example, a respondent may answer that over the next 12 months, there is a 50% probability that inflation will be between 0% and 2% and a 50% probability that it will be between 2% and 4%.

Using this data, we calculated respondents’ inflation uncertainty as the standard deviation of different anticipated rates of inflation and their associated likelihoods.While the SCE calculates inflation uncertainty in a slightly different manner (see the New York Fed’s methodology document (PDF) for more information), the results it produces are very similar to those using our measure of inflation uncertainty. Our inflation uncertainty variable is the square root of the SCE’s “Q9_var” variable. Standard deviation is a statistical measure of how wide a distribution of outcomes is. In the present case, a high standard deviation indicates that a respondent thinks the inflation rate is less likely to be centered more narrowly around a specific level, suggesting high uncertainty about future inflation. In contrast, a low standard deviation indicates that a respondent assigns a higher likelihood to a specific inflation rate, meaning the respondent is relatively certain about future inflation.These standard deviations are not necessarily associated with what respondents expect the level of inflation will be, merely how uncertain they are about the future rate of inflation.

We compared the level of one-year-ahead inflation uncertainty reported by respondents in the Eighth District to the level of one-year-ahead inflation uncertainty reported nationwide from 2013 to 2023, the current span of the survey. We used responses from four large cities in the Eighth District—Little Rock, Ark.; Louisville, Ky.; Memphis, Tenn.; and St. Louis—to approximate inflation uncertainty in the region. Our sample included about 40 respondents each month from the Eighth District.

In the figure below, we plot the median inflation uncertainty among Eighth District respondents (light blue line) and the median inflation uncertainty nationwide (dark blue line). Because the Eighth District has far fewer survey respondents than the nationwide sample, the national median response tends to be more stable—have less variability—than the Eighth District median response. The median inflation uncertainty in the nationwide sample remained relatively consistent from 2013 to 2020, then began to climb slightly after the start of the pandemic. This indicates that with the onset of COVID-19, survey respondents became less certain about the future course of inflation. The effect was especially pronounced for Eighth District respondents, who reported high inflation uncertainty during three distinct periods: late 2016 into 2017, 2020, and 2022. During these periods, inflation uncertainty in the Eighth District more than doubled. Inflation uncertainty reported in the Eighth District was also significantly higher than the national median during these three periods, but it was quite similar—albeit more volatile—during the rest of the sample period.

Dispersion of Inflation Expectations for the U.S. and Eighth District, 2013-2023

SOURCES: New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: Data are monthly from June 2013 through April 2023, the most recent month for which the necessary survey microdata were available.

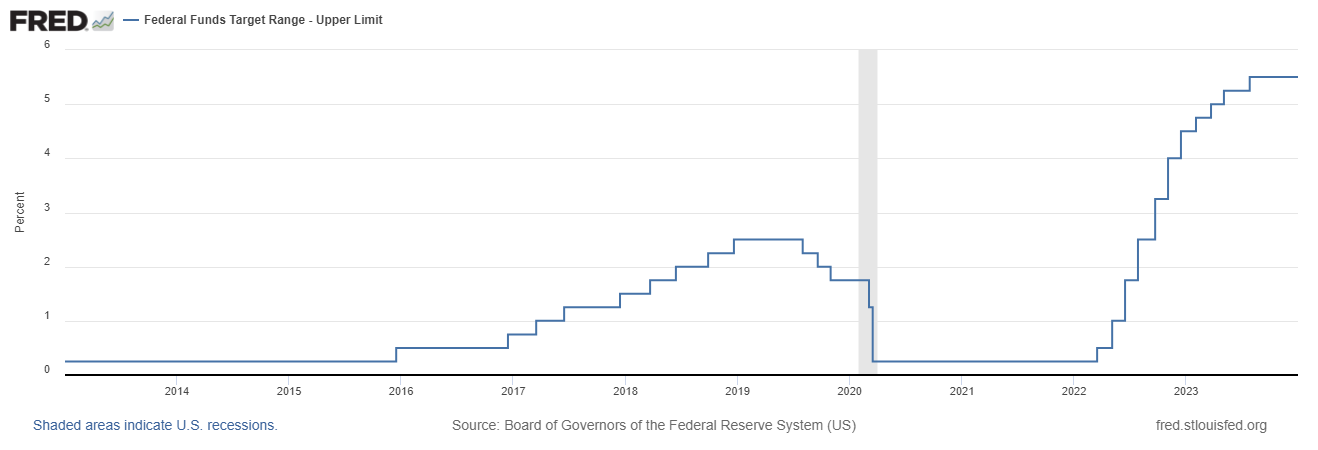

The three episodes during which Eighth District respondents reported high inflation uncertainty correspond to periods in which the FOMC changed the stance of monetary policy (see the following FRED chart). In 2017, the FOMC began to steadily tighten monetary policy after a long period of near-zero interest rates. In early 2020, it abruptly cut the target range for the federal funds rate in response to the pandemic. Finally, at the start of 2022, the FOMC began quickly raising the target range for the federal funds rate in response to high inflation. Since the FOMC shifts policy largely to maintain an inflation target of 2%, the large spikes in uncertainty that we observed in the figure above could be construed as Eighth District respondents having less confidence in the ability of the Federal Reserve to maintain price stability, an important part of its mission.

Implications of Inflation Uncertainty for Households

In periods with elevated inflation uncertainty, Eighth District survey respondents reported a set of inflation expectations with a median standard deviation of around 4% to 5%, roughly 3 percentage points higher than its baseline—that is, pre-2016—level.

Why do changes in inflation uncertainty matter? To put this into perspective, assume that people think the possible outcomes of inflation are normally distributed; that is, they follow a simple bell shape around the most likely outcome, with extreme values less likely to occur. During the periods of baseline inflation uncertainty, households holding a bond that offers a 5% nominal return will be 70% certain that the real return will land between 4% to 6%, taking into account how inflation affects the gain or loss in purchasing power. During the periods of elevated inflation uncertainty, the likely range of returns widens to 1% to 9%, with a 15% chance of the unfortunate outcome of a real return lower than 1%. With this increase in uncertainty, lenders will demand a higher expected return to compensate for their risk, which might impair the ability of households and businesses to borrow.

To conclude, we found that Eighth District households had large increases in inflation uncertainty during periods of significant change in monetary policy, especially after the start of the pandemic. Understanding why survey respondents in the Eighth District reported more inflation uncertainty during these periods than survey respondents did nationally calls for future research, as managing inflation expectations is a critical part of the Fed’s mission.

Notes

- The Eighth District, headquartered in St. Louis, includes all of Arkansas, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, northern Mississippi, eastern Missouri and western Tennessee.

- While the SCE calculates inflation uncertainty in a slightly different manner (see the New York Fed’s methodology document (PDF) for more information), the results it produces are very similar to those using our measure of inflation uncertainty. Our inflation uncertainty variable is the square root of the SCE’s “Q9_var” variable.

- These standard deviations are not necessarily associated with what respondents expect the level of inflation will be, merely how uncertain they are about the future rate of inflation.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us