Interest Rate Risk, Bank Runs and Silicon Valley Bank

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- When commercial banks borrow—from depositors and other sources—over the short term and lend for long periods, it creates the risk that rising interest rates will reduce the value of their long-term assets.

- Bad news or a large drop in asset values may worry depositors and trigger a bank run, which could put a bank out of business if it cannot quickly liquidate assets to meet demands for withdrawals.

- Bank runs can hurt the broader economy by disrupting business relationships.

- Two types of policies have greatly reduced the incidence of bank runs: emergency lending facilities—i.e., lenders of last resort, like central banks—and deposit insurance.

At any given time, some people are saving money, perhaps for emergencies or for college or retirement, while others want to borrow money to buy a house or a car or invest in a business. The largest borrowers—such as governments or large corporations—can sell bonds to raise capital, while smaller borrowers—e.g., smaller companies or individuals—tend to borrow from banks because it would be expensive and risky for savers to evaluate the creditworthiness of smaller borrowers. Banks specialize in evaluating the creditworthiness of borrowers, intermediating between borrowers and lenders.

To obtain funds to make loans, banks borrow from individuals and firms over the short term in the form of deposits. Savers like quick access to their money in case of emergency—such as a job loss—so banks commonly offer demand or savings deposits, which allow depositors to get their money back immediately, or certificates of deposit (CDs), which typically mature in a few months to a few years. In contrast, many firms and individuals want to borrow over the long term for projects, such as building a factory, or major purchases, such as buying a house.

Banks perform a maturity transformation when they borrow over the short term and lend for long periods. This transformation creates a potential problem, though: Depositors might demand their money from banks before borrowers repay their loans. Banks keep funds in reserve for the depositors who want to get their money out, with some extra for insurance, but can’t pay off all their depositors at once.Banks use a number of liabilities other than deposits to fund loans, including federal funds purchased, brokered deposits and borrowings from Federal Home Loan Banks. These all tend to be more expensive than deposits.

Interest Rate Risk in Maturity Transformation

Borrowing over short periods and lending for long periods generally allows banks to make money, because long-term interest rates are usually higher than short-term interest rates. But this strategy carries the risk that interest rates will rise, reducing the value of a bank’s long-term fixed-rate assets—usually loans or bonds—because higher interest rates reduce the present value of the payoffs to those loans or bonds.Another channel of interest rate risk occurs when a general rise in interest rates forces banks to pay higher interest on deposits but produces only slow increases in bank revenue as new long-term loans are made at higher interest rates. In practice, however, deposit rates typically rise much more slowly than other short-term interest rates. Potential decline in asset values because of an increase in interest rates is known as interest rate risk or duration risk, and it can reduce a bank’s net worth (assets minus liabilities).

Banks can mitigate interest rate risk in several ways, but most are costly and involve reducing the bank’s net amount of maturity transformation. For example, a bank wishing to hedge (reduce) interest rate risk might lock in longer-term deposits in the form of CDs or time deposits, or make more short-term loans instead of long-term loans. Properly managing interest rate risk is a critically important task for banks.For more on this issue, see the Feb. 9, 2023, blog post “Rising Interest Rates Complicate Banks’ Investment Portfolios” by St. Louis Fed Senior Vice President Carl White.

Characteristics of Bank Runs

If depositors learn of such a decline in their bank’s net worth, they might fear for the bank’s solvency and the safety of their deposits and transfer their money to a safer bank. An attempt by many depositors to simultaneously withdraw their money is called a bank run, and such an episode can put a bank out of business. Even if the value of the bank’s assets (loans and securities) exceeds that of its liabilities (deposits and borrowings), a bank cannot quickly liquidate its assets to immediately pay off all its liabilities.

A curious thing about bank runs is that they can be self-fulfilling prophecies. If many depositors seek to simultaneously withdraw their money, the attempt puts the bank at risk, and so it makes sense for other depositors to withdraw their money, too, whether or not the bank run is actually justified by fundamentals. Economists Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig formalized this possibility in a well-known paper (PDF), for which they shared the 2022 Nobel Prize in economics with Ben Bernanke.

Bank runs can damage the economy because they disrupt relationships between borrowers and lenders, and uninsured depositors can lose their money. Removing banks from their role of mediating between savers and borrowers is called disintermediation. During the early part of the Great Depression, thousands of banks failed. Many economists consider this to be one of the Great Depression’s principal causes (PDF).

Policies to Mitigate Bank Runs

Two types of policies have greatly reduced the incidence of bank runs: emergency lending facilities, i.e., a lender of last resort, and deposit insurance.

A fundamentally sound bank whose assets are greater than its liabilities might still fail if it is unable to satisfy its depositors’ demands for funds during a bank run. One solution to this problem is to borrow against the bank’s illiquid assets, such as business or commercial real estate loans. But bank runs often occur during a financial crisis, when it is difficult or impossible to borrow, even against good collateral. A solution to this problem is to create an emergency lender—a lender of last resort—with very deep pockets that can provide loans during the worst times. Central banks have long had the duty to lend to illiquid but solvent financial institutions in such times of crisis. Indeed, a major purpose for which the Federal Reserve was created was to be a lender of last resort.

Deposit insurance also helps reduce the frequency of bank runs by reducing the incentives for depositors to withdraw their money at the first sign of trouble. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) guarantees bank deposits up to $250,000 per depositor, per bank, meaning that no depositor with deposits less than or equal to this figure will lose money.Similarly, the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund insures credit union accounts. Banks may still be subject to runs, however, if uninsured depositors fear that they will lose their money in the event of a bank failure.

Deposit Insurance Alters Incentives

While deposit insurance helps guard against bank runs, it has a disadvantage in that it removes a source of market discipline on banks: Insured depositors no longer have an incentive to track and evaluate banks’ financial health.Commercial banks must submit quarterly balance sheet and income statements, known as Call Reports. To review a bank’s Call Report, one can access the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s Central Data Repository. Federal deposit insurance hasn’t automatically covered all deposits partly because larger depositors are thought to be sophisticated enough to evaluate banks’ financial health, thereby providing banks an incentive to behave prudently. Extending deposit insurance to larger depositors would remove this incentive and increase the fees banks must pay the FDIC for insurance coverage. Because deposit insurance greatly reduces depositors’ incentives to withdraw their funds at the first sign of trouble, insured deposits tend to be much more stable than uninsured deposits.

The Run on Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank had several risk factors for a run. This $200 billion bank catered to, and was thus dependent on, the tech sector. When tech was booming, the bank grew very quickly, thanks to a large influx of uninsured deposits from venture capital and tech firms, which were used to meet payroll and operating expenses. Silicon Valley Bank largely invested these deposits in long-term bonds, especially mortgage-backed securities, in an effort to increase yield and bank earnings at a time when interest rates were very low. But the values of these bonds were highly sensitive to interest rate increases.

The 2021-22 surge in inflation prompted the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to raise the federal funds rate target range from 0%-0.25% on March 16, 2022, to 4.75%-5% by March 23, 2023. On March 8, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank posted a $1.8 billion loss on the sale of $21 billion of these securities and announced a plan to raise capital. Uninsured depositors saw these moves as signs of bank distress, word started circulating on social media, and the next day customers withdrew more than $40 billion from the bank. It was a modern twist on a classic bank run in that the deposits could be quickly withdrawn electronically. Silicon Valley Bank could not sell or borrow enough against its assets to meet the demands for deposits. The California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation seized the bank on March 10, 2023.In late April, the Federal Reserve released a review of its supervision of Silicon Valley Bank. The report analyzed the actions of bank management and Fed supervisors that preceded the failure. See the full report (PDF).

The run on Silicon Valley Bank kicked off fears that there would be runs against banks in similar situations. Signature Bank in New York, a $100 billion institution, ran into similar problems with uninsured depositors pulling their funds, leading the New York State Department of Financial Services to close the institution on March 12, 2023.

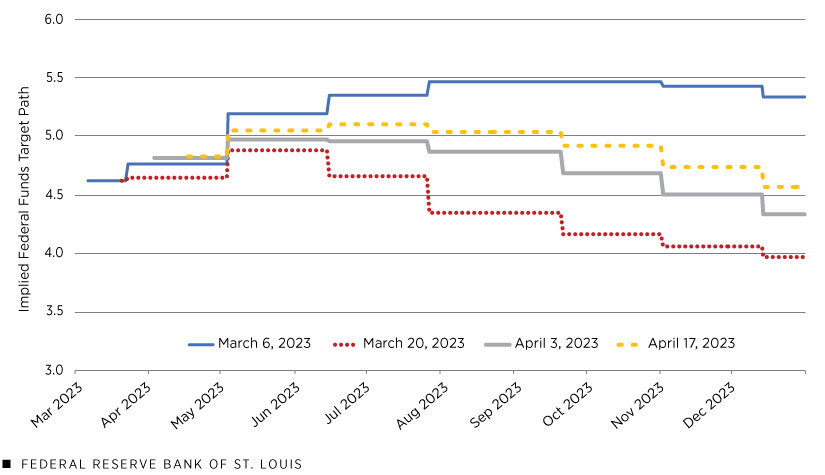

In response to the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, market expectations of near-term interest rate increases declined in mid-to-late March, and banks further tightened terms on loans, making credit harder to get.The Fed’s January 2023 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices noted tightening credit conditions before the March bank failures. The following figure shows that market expectations of the middle of the federal funds target range declined substantially between March 6 and March 20, before partially recovering by the middle of April.

Futures-Implied Expected Paths for the Middle of the Federal Funds Target Range

SOURCE: Chicago Board of Trade via Haver.

NOTES: The figure displays the expected paths of the middle of the federal funds target range implied by federal funds futures prices as of March 6, 2023, March 20, 2023, April 3, 2023, and April 17, 2023, assuming target changes occur only at scheduled FOMC meetings and that the average federal funds rate is in the middle of the target range.

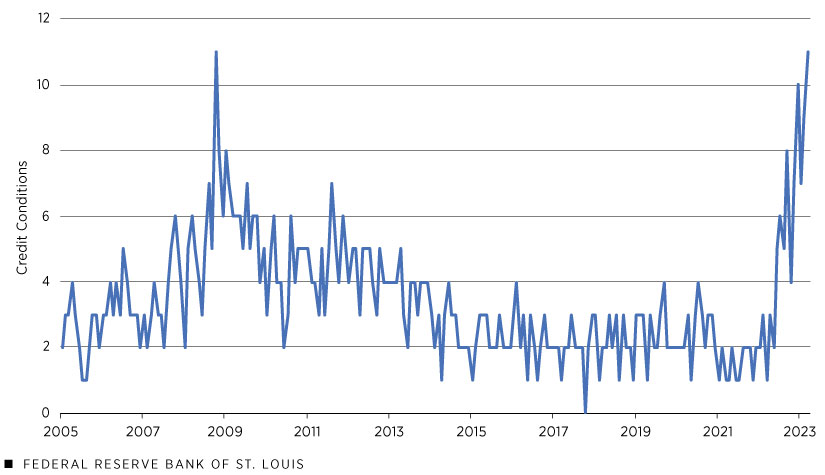

The figure below shows that credit conditions for households in March 2023 were tighter than at any time since October 2008. In addition, capital markets temporarily froze up, with corporations issuing very few bonds in the weeks following Silicon Valley Bank’s failure.

Credit Conditions for Buying Large Household Goods

SOURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers via Haver.

NOTE: Higher numbers indicate tighter credit conditions for purchasing large household goods.

The financial stress associated with the failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and, more recently, First Republic Bank remind us that modern economies still depend on traditional financial institutions. And even with mitigating policies such as central bank emergency lending programs and deposit insurance, bank survival depends on bank executives properly managing assets and liabilities.

Notes

- Banks use a number of liabilities other than deposits to fund loans, including federal funds purchased, brokered deposits and borrowings from Federal Home Loan Banks. These all tend to be more expensive than deposits.

- Another channel of interest rate risk occurs when a general rise in interest rates forces banks to pay higher interest on deposits but produces only slow increases in bank revenue as new long-term loans are made at higher interest rates. In practice, however, deposit rates typically rise much more slowly than other short-term interest rates.

- For more on this issue, see the Feb. 9, 2023, blog post “Rising Interest Rates Complicate Banks’ Investment Portfolios” by St. Louis Fed Senior Vice President Carl White.

- Similarly, the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund insures credit union accounts.

- Commercial banks must submit quarterly balance sheet and income statements, known as Call Reports. To review a bank’s Call Report, one can access the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s Central Data Repository.

- In late April, the Federal Reserve released a review of its supervision of Silicon Valley Bank. The report analyzed the actions of bank management and Fed supervisors that preceded the failure. See the full report (PDF).

- The Fed’s January 2023 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices noted tightening credit conditions before the March bank failures.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us