Eighth District Farmers Navigate Global Supply Uncertainty

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Successive shocks have disrupted global supplies of fertilizer and other agricultural inputs, raising prices and generating uncertainty for farmers worldwide.

- In response to increased fertilizer costs, Eighth District farmers have adjusted crop production and formed unofficial purchasing co-ops to negotiate better prices.

- Measures of financial stress are well below levels seen in past farm crises, suggesting that U.S. agricultural firms remain in a relatively strong financial position.

The global agriculture sector is no stranger to price swings, but the past few years have presented several shocks in rapid succession. Disruptions related to COVID-19 and shortages accompanying global conflict, along with price increases, have all contributed to greater uncertainty for domestic farmers. But there is good news for agricultural firms navigating these issues: A strong financial position has given the sector much-needed stability moving forward.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the agricultural industry had been dealing with global disruptions that brought shortages and price increases in key inputs. Chief among these was the rapid rise in fertilizer prices in 2021.

Commercial fertilizers are a critical input for agriculture across the globe, although specific requirements for type and application vary by region and crop. Fertilizer production relies on chemical inputs to create synthetic nutrients; modern commercial fertilizers are manufactured by mixing atmospheric nitrogen with hydrogen from natural gas to create ammonia, which is then typically mixed with phosphorus and potassium.

While fertilizer demand is global, the resources needed to produce it are not. Canada, Russia and Belarus supply two-thirds of the world’s potassium.See the June 2022 U.S. Department of Agriculture report Impacts and Repercussions of Price Increases on the Global Fertilizer Market. Likewise, China produced more than 35% of global phosphorus from 2017 to 2019. This concentration of key materials means that disruptions in a few countries can raise global prices and produce shortages.

An untimely combination of supply chain bottlenecks, natural disasters and global upheaval has led to just this outcome. In late August 2021, Hurricane Ida disrupted chemical production on the U.S. Gulf Coast. China implemented new customs inspections on fertilizer inputs in October 2021, then restricted fertilizer exports in 2022 to protect its domestic supply. All the while, the same pandemic-related delays that slowed supply chains around the globe also affected chemical shipments. Conditions worsened further when the conflict in Ukraine caused natural gas prices to rise. Subsequent sanctions on Russia and Belarus have contributed to uncertainty in the fertilizer supply because of their effects on the natural gas supply and, by extension, the availability of the ammonia needed to produce nitrogen fertilizers.

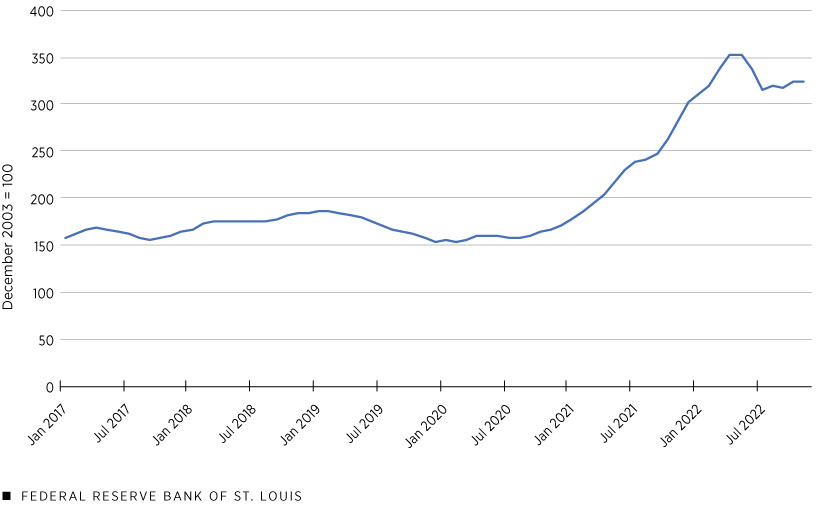

As the following figure illustrates, nitrogen fertilizer prices, as measured by the producer price index (PPI), rose 77% from December 2020 to December 2021. The PPI measures changes in prices received by domestic producers, so it reflects farmers’ input costs. Though the rate of growth slowed slightly in January 2022, prices increased 6.2% in March and 4.1% in April before finally falling slightly in May and June. Prices have remained fairly stable since then.

Rising Prices: U.S. PPI for Nitrogen Fertilizer, January 2017-November 2022

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Impact of Fertilizer Price Increases in the Eighth Federal Reserve District

How will these price increases affect producers in the Eighth Federal Reserve District? First and foremost, it’s important to remember that agriculture has significant lags; fertilizer for the 2022 planting season was purchased in 2021, and it will take longer still for the price increases to be passed on to consumers after crops are harvested. However, these price increases likely will be passed on, because crop prices and fertilizer prices are (unsurprisingly) highly correlated.

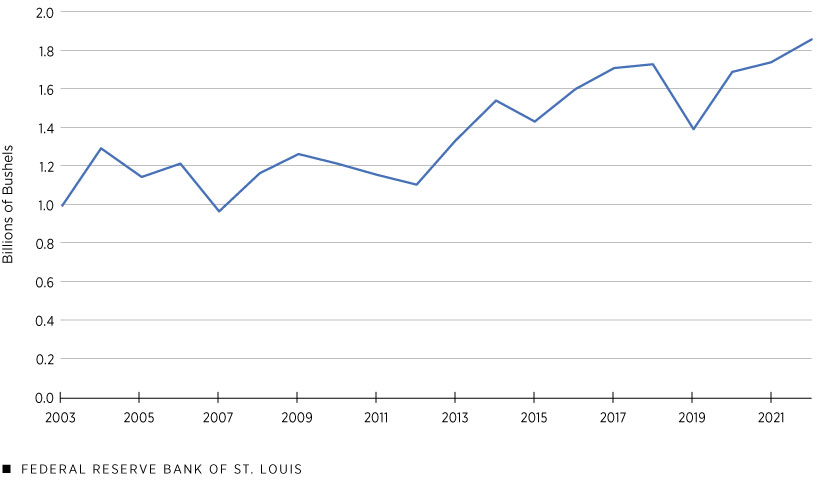

Despite these lags, changes in crop composition already are visible. Corn requires more nitrogen fertilizer than soybeans do, because soybeans work with bacteria to pull nitrogen from the atmosphere (a process known as nitrogen fixing). Because of this, some farmers have shifted their crop mixes with the goal of using less fertilizer, replacing corn with soybeans and other less fertilizer-intensive crops.

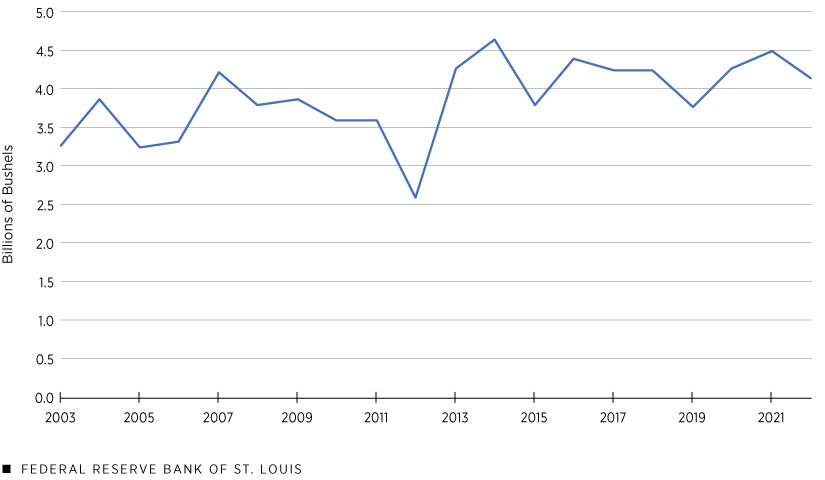

This effect is being felt across the Eighth District and nationally. As the figures below show, corn production in the region fell 7.8% from 2021 to 2022, while soybean production rose 6.6% during that same period. These figures are drawn from state-level U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data and include the states that fall entirely or partially within the Eighth District: Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee.

Corn Production in the Eighth District, 2003-2022

Soybean Production in the Eighth District, 2003-2022

SOURCE FOR THE TWO FIGURES: USDA.

Nationally, the USDA’s August 2022 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report (PDF) downgraded forecasts for corn production and yields from July and raised forecasts for soybean production and yields. Similarly, the July 2022 Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report indicated that of the farmers who planned to shift their crop mixes, almost half anticipated allocating a higher percentage of their acreage to soybeans.

To combat fertilizer price increases, regional farmers have grouped together to order fertilizer as a collective. The benefits of doing so are straightforward: Because the collective, or co-op, can make a significantly larger order than any individual, it can attempt to lock in prices that are more manageable for single farmers. Regional farmers have noted that these unofficial buying structures have become more common as fertilizer price increases continue to impact corn and soybean farmers.

Summer 2022 Shocks

Fertilizer prices are just one issue facing the agriculture sector. The unavailability of mechanical parts also has been a challenge for farmers, with agricultural equipment subject to the same raw material and computer chip supply chain issues that have hampered auto production. Labor, too, became a point of concern during the pandemic, though the end of pandemic-related travel and immigration restrictions have brought relief on this front.

More recently, weather events and commodity price swings have produced uncertainty in the agriculture sector. Drought in the U.S. Southwest and flooding in the Great Plains have reduced production in both regions. Record heat and meager rainfall prompted U.S. cotton farmers to reduce their cotton acreage last growing season; the USDA forecasted a domestic cotton harvest 28% lower than the previous year’s, which would mark the smallest harvest since 2009. Although some areas of the Eighth District were impacted by floods or drought, the region as a whole avoided large-scale disruptive weather events during the 2022 planting season, which has helped corn and soybean production remain largely on normal trend.

Financial Position

The agriculture sector endures shocks and price fluctuations as a matter of course. And while farmers may be concerned about uncertainty, measures of financial stress indicate that the sector is in a better position than it was in previous financial crises. The USDA’s debt service and debt-to-asset ratios have risen slightly in recent years, but they remain well below where they were in the farm crises of the 1980s. The sector maintains ample liquidity, and the Farm Credit Administration reports strong credit quality; the share of nonperforming loans reached a five-year low of 0.45% in 2021. While this measure rose slightly to 0.49% in the first half of 2022, it remains below the 0.79% recorded in 2019.

Self-reported measures of financial stability tell a similar story. While conditions have weakened in recent months, agricultural producers are well clear of all-time lows. The Purdue University Farm Financial Performance Index, which measures current financial conditions among farmers, sat at 91 in November, up from 86 in October.See the December 2022 Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report. While down from 113 in December 2021, recent upward movement reflects high crop prices and strong revenue expectations for the current year. Longer-term expectations are softer, however, with Purdue University’s Farm Capital Investment Index at an all-time low of 31 in November.Again, see the December 2022 Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report. Reports from Eighth District agricultural producers delivered the same message: While rising interest rates and input costs could affect the market in 2023, for the time being farmers remain on stable financial ground.

Eighth District Farmers Weather Global Disruptions

Fertilizer is a critical input for global agriculture. An untimely series of shocks has reduced the global supply of fertilizer and other agricultural inputs and increased delivery times, raising prices and generating uncertainty for farmers across the world. Nonetheless, Eighth District farmers largely remain in a solid financial position. In response to the rise in fertilizer prices, they have adjusted the distribution of their row crops and formed purchasing co-ops to negotiate for better sales terms.

Notes

- See the June 2022 U.S. Department of Agriculture report Impacts and Repercussions of Price Increases on the Global Fertilizer Market.

- See the December 2022 Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report.

- Again, see the December 2022 Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us